It’s hard to know how to follow yesterday’s yarn about my recent small-hours radio ‘haunting’, but since Shropshire landscapes cropped up in it, I thought I’d have a ‘rummage’ through that particular photo file. And so I found this one of me, courtesy of he-who-builds-sheds-and-greenhouses in the days before he did such things.

It must have been taken in the second winter after we left our life in Kenya. We had settled in Rochester, Kent. For the eight years we’d been living in Africa, Graham had been employed by the Natural Resources Institute (NRI), once the scientific arm of British Government overseas aid, but now part of the University of Greenwich. Its offices were based in the old Chatham dockyard, just up the road from Rochester. (Odd factoid: both locations have strong Charles Dickens connections). And so Graham was returning to base, though he had never had a desk there. It was a strange situation.

Neither of us wanted to be there. For one thing we were overwhelmed by the hemmed-in urban congestion of the Medway five towns: Strood, Rochester, Chatham, Gillingham and Rainham massing together so closely so that once in their midst, you could not see out or move for traffic. The one source of local relief was the River Medway that wound between them. We had bought a house there – in one of the new riverside developments that were sprouting up along its banks.

A little oddly too, our particular townhouse enclave was on the site of the old Short Brothers Empire flying boat factory, the craft that had served Imperial Airways during their 1930s pioneering of air travel to Africa, India and beyond. Later Imperial morphed into BOAC (British Overseas Airways Corporation), and I remembered that some of the first flights to Kenya used to land on Lake Naivasha and, while the crew put-up in the cottages of the Naivasha Country Club (where we ourselves had once stayed), travellers to Nairobi would have to complete the last sixty miles by dirt road.

The connection was a small ‘haunting.’ Added to when one of our first house guests, an expat friend from Nairobi (actually an Englishman who had settled in Australia) told us that his father had been a steward with Imperial Airways. (This was the same person who, on another visit from Australia, came to stay with us in Much Wenlock, and on arrival told us he had a cousin living up the road).

*

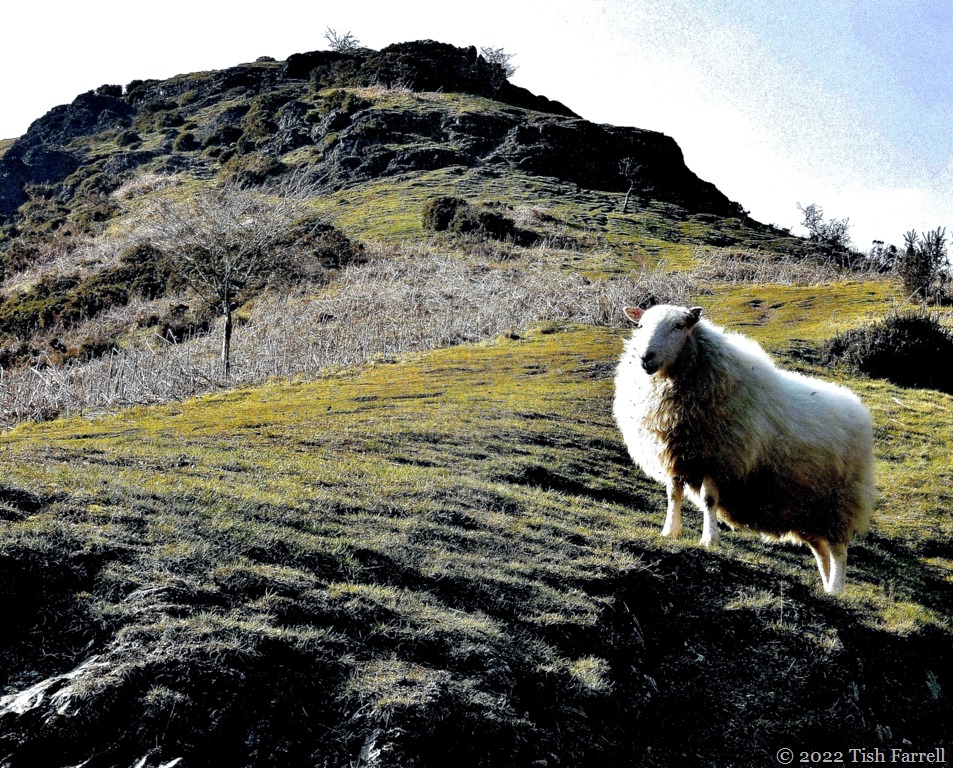

But back to the header photo. One of my adjustment strategies to UK life was to go to T’ai chi classes. This then explains the pose. I think I am in the throes of grasping the sparrow’s tail.

But what of the location?

One reason we didn’t want to be living in Kent was because family and friends were mostly faraway in the West Midlands: Shropshire and Staffordshire – and between them and us was the evil M25 London orbital car park motorway. We could access it in either direction from Rochester. It never made any difference. The jams seemed to last for days.

But then the photo shows we must have broken out. Here we are in Shropshire in late December 2001. It is one of the county’s most mysterious locations: Mitchell’s Fold, a Bronze Age stone circle, sitting on the borderland with Wales. I don’t remember now why we chose to be driving round the Shropshire hills in such wintery weather, but there’s more about that visit and the circle’s folk lore associations with wicked witch Mitchell here: Witch Catching In The Shropshire Hills

Copyright 2022 Tish Farrell

The Square Odds #3