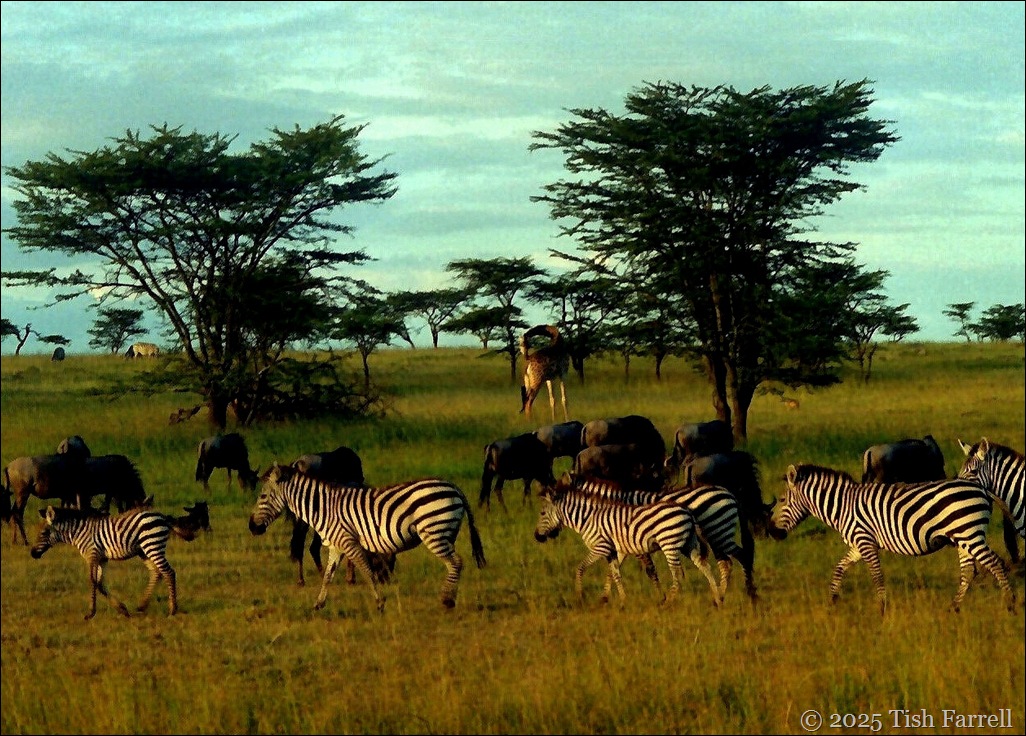

Green lane, hollow way, sunken road: there’s a hint of mystery in these byways, not only in the names, but in the sense of times past, centuries of footfall embedded in the earth between ancient hedges; the passing of cottage folk, farmers, drovers with their herds and flocks; times when most people only had their feet to rely on if they needed to go anywhere.

This particular green lane is one of my favourite spots in Bishop’s Castle. The following photos are ones I forgot to post, taken on a late November walk. It was a brilliant day too, following a brief snow fall and several days of hard frost.

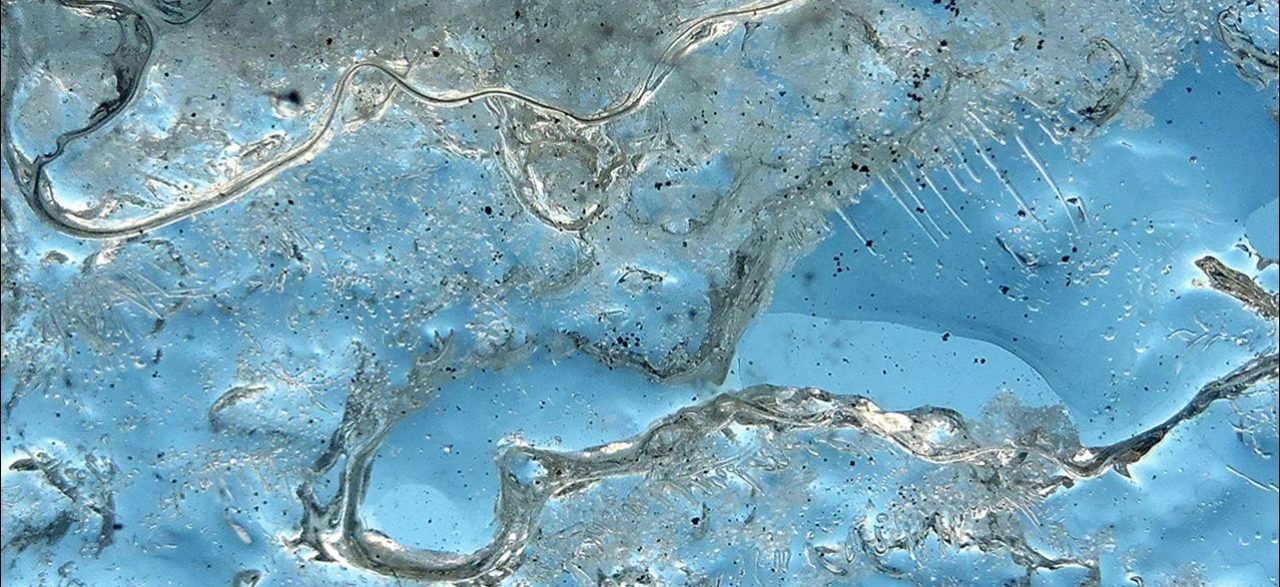

The frozen grass and leaves were crunchy under foot, gripping boots and making the walking easy as we climbed up Wintles Hill. We were heading to the dew ponds.

There are essential landmarks en route of course: a hoar-frosty Long Mynd…

*

The barns with their rusty roofs that always insist on having their photo taken…

*

The skyline ash tree that looks like an arboreal version of Munch’s ‘The Scream’…

*

As for the dew ponds, there are three on the hilltop, one very much in use, as you can see from the well-pocked mud around it…

*

One dwindling in the next door arable field and so only used by wildlife…

*

And the largest in a now enclosed enclave where it is producing a fine crop of bullrushes…

I don’t know why this corner of the field has been hived off, access provided by two stout kissing gates either side of it, but the Shropshire Way footpath passes through it.

It’s a good spot for holly trees, which reminds me. Holly was once grown in farm hedges both to shelter stock and as a valuable winter fodder for sheep (and sometimes cattle) when hay was in short supply. And yes, it does seem an unlikely foodstuff with all those prickles, but apparently the leaves become less barbed as the tree grows taller. And so it was the upper branches that were lopped off for the animals to feed on, the holly trees doubtless thriving on the pollarding (if our brute of a garden holly hedge is anything to go by).

*

Water was the other essential in hill country where streams were lacking. Dew ponds have been used at least since Neolithic times. They were also much used in mediaeval times and in the 18th-19th centuries, both periods reflecting a vibrant market for sheep wool.

Pond construction required skill and heavy labour. First a saucer shaped depression was excavated, about 3 feet (1 metre) deep. The diameter varied between 10 feet (3 metres) to 45 feet (15 metres). The whole surface was then covered with straw followed by a layer of mud which had to be puddled to seal the surface. (Canal beds were sealed in the same way, the puddling usually done by labourers in bare feet). Once sealed, rain and field run-off duly collected in the ponds.

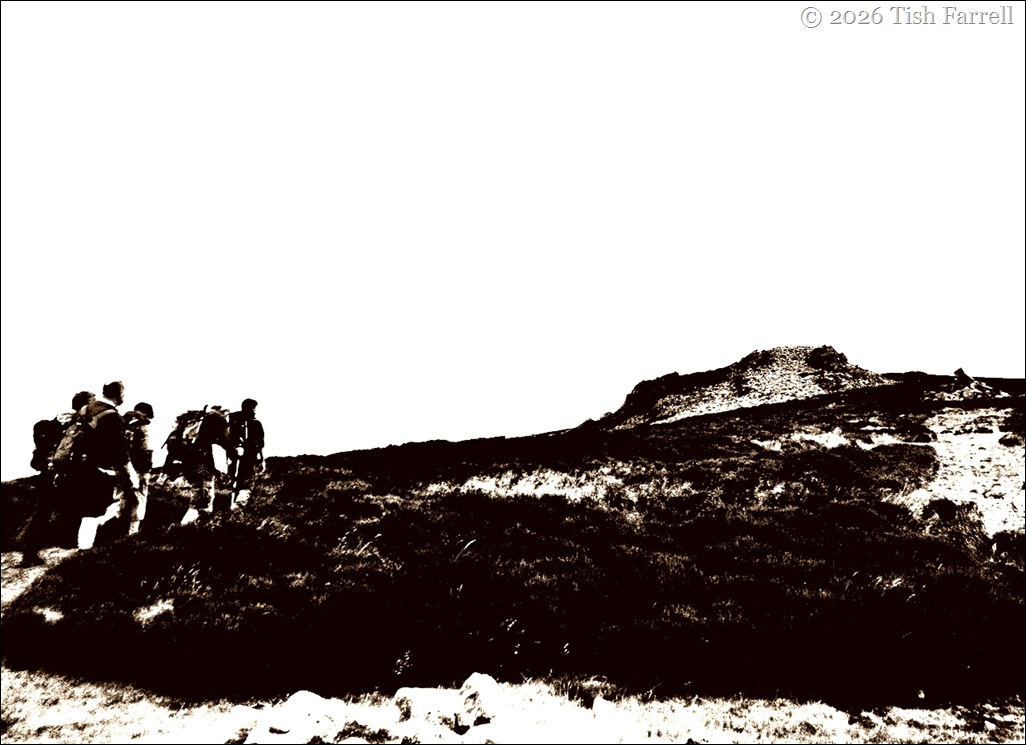

In the past, Welsh drovers would have driven their stock through Bishop’s Castle, and on to the town and city markets of the Midlands. This next photo shows the country they would have trekked through – not so tamed and tidy in the eighteenth century. (Wales ahead, dewponds behind me). Perhaps the flocks and herds were gathered and watered at points like these before the drovers broached the town.

*

And it was at this moment that thoughts of watering holes had us turning on our heels and heading downhill to town. Toasted sandwiches at The Castle Hotel suddenly beckoned, plus a glass of delicious Clun pale ale.

Cheers and happy festive season to all the Lens-Artists (and their followers).

Many thanks for setting us so many diverting challenges through 2025.

*

Lens-Artists: Last chance for 2025 This week Patti sets the theme: last chance to post photos that missed previous posting opportunities.