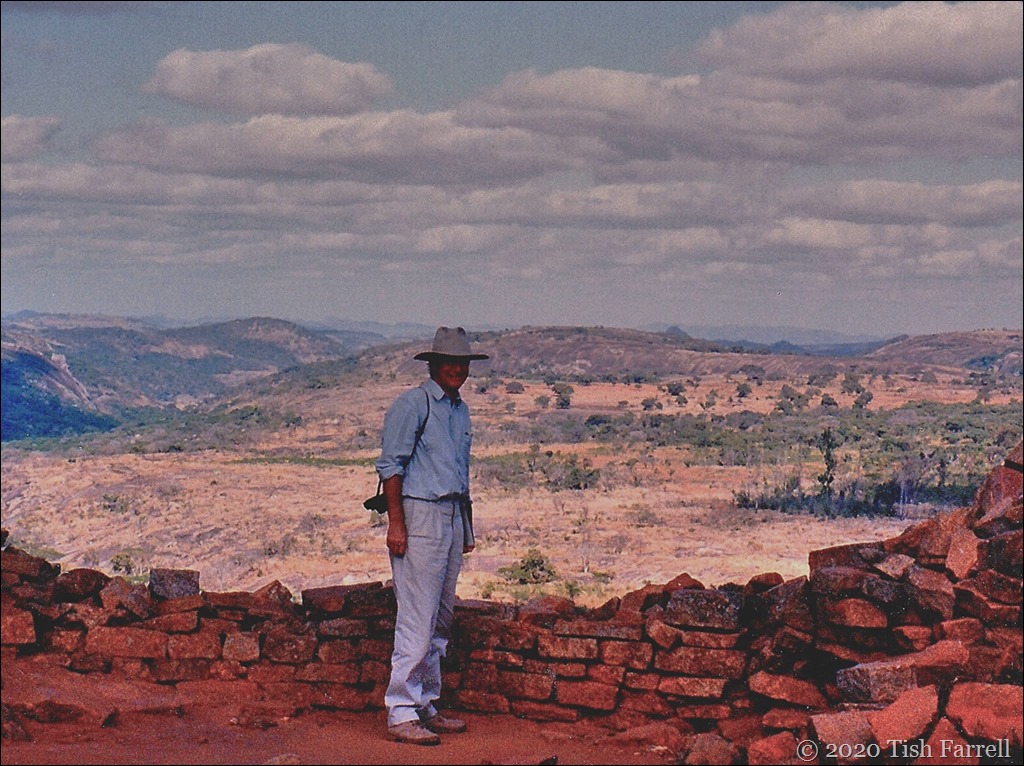

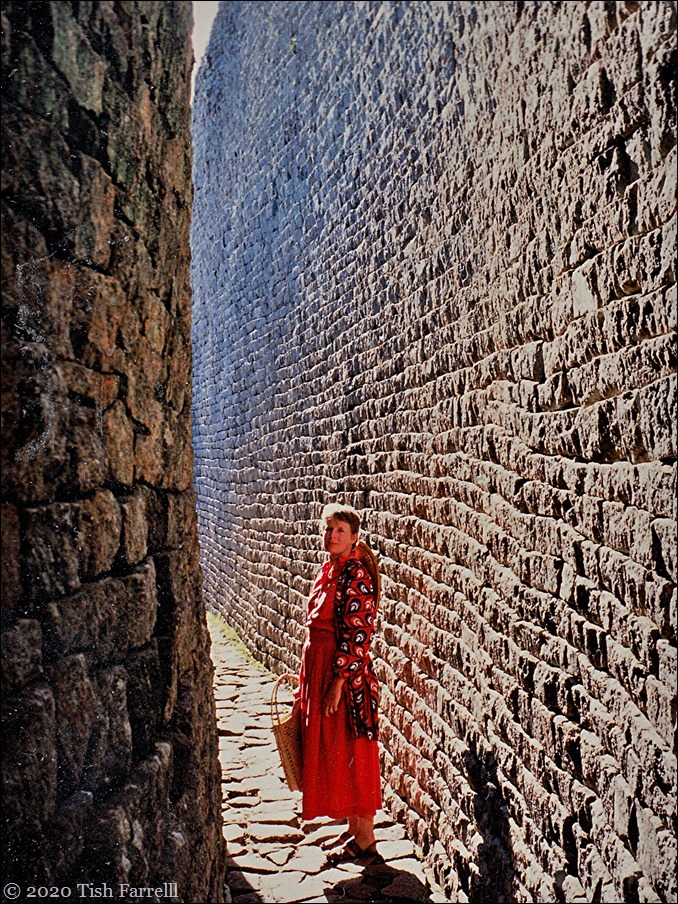

I’m thinking we did dream it. These vintage scenes look unreal. I remember it as a perfect day, though more drowsy English summer – the sort we like to think once happened – than an actual African afternoon. It was July, southern Africa’s winter, the daytime temperatures cool enough for me to be wearing my Zambian cotton jacket, at least in the shadows within the Great Enclosure. Strangely, we had the ruins to ourselves, us and our two companions. For a time, before starting our exploration, three of us had sat outside on the grass, our backs against the enclosure’s monumental, drystone wall. The air was still; the granite warm.

We were living in Zambia at the time, but were on a two-week road trip across Zimbabwe. This ancient African city was a high spot on the itinerary. Yet the conversation below the great wall wound on; quite unrelated to the place we were. Crickets chuntered. Time passed. A sense of treading water. Soon we would have to move on to find somewhere to stay for the night. It was all unknown territory. We had nothing booked. There was a moment when I thought if I don’t break free of this reverie, my one-time chance to see this place will be lost. It almost was.

*

Amy at Lens-Artists asks us for precious moments. It was hard to choose from our eight-year stay in Africa. It often felt we were present for all of it – all senses always switched full on. But Great Zimbabwe was certainly one of highest high spots. I still have that jacket too, stitched by hand from cloth bought in a Livingstone store, near Victoria Falls.

Many of you have seen these photos before, but I’m sure you don’t mind another look. I’m also reprising the text of a long-ago post for those who want to know something about the ruins.

Great Zimbabwe

No one knows exactly why this great African city was abandoned. For some 350 years, until around 1450 AD, Great Zimbabwe had been a flourishing merchant centre that drew in from the surrounding country supplies of gold, copper, ivory, animal skins and cotton. The city’s entrepreneurs then traded these goods on to the Swahili city states of Sofala and Kilwa on the East African coast. (You can read more about the Swahili HERE). In return, the traders brought back luxury goods including jewellery, Chinese celadon dishes and Persian ceramics.

The city’s ruins cover 80 hectares, its many stone enclosures commanding the southern slopes of Zimbabwe’s High Plateau watershed between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers. The site is well watered with good grazing throughout the year. It is above the zone of the deadly tsetse fly that can infect both cattle and humans with sleeping sickness; and the plateau’s granite scarps provide plentiful building stone and other raw materials.

Even so, these favourable circumstances do not explain why this settlement rose to such particular prominence. Great Zimbabwe was not a singular phenomenon. Contemporary with it, and across the High Plateau region, are the remains of at least a hundred other mazimbabwe (houses of stone) settlements. Several were large enough to have been the capitals of rival states. Others may have been satellite communities occupied by members of Great Zimbabwe’s ruling lineage.

So who were the city’s builders?

During Zimbabwe’s colonial times, and until independence, the Rhodesian government actively supressed evidence that Great Zimbabwe was built by Africans. Many of the other stone ruins were destroyed or re-purposed by European settler farmers. The official view claimed that the city was Phoenician, and that the Queen of Sheba’s fabled kingdom of Ophir had been discovered. Archaeologists, however, have long demonstrated that it was the cattle-owning Karanga Shona who built Great Zimbabwe. The first phase of stone building began around 1100 AD. Thereafter, the city’s rising fortunes and successive building phases suggest its increasing control of the ancient High Plateau trade routes to the Swahili cities of Sofala and Kilwa.

Gold was the key commodity, and it is likely that it was Great Zimbabwe’s successful cattle production that provided it with the trading power to secure gold supplies from mines some 40 kilometres away. The more prosperous the city became, the more sophisticated its demonstrations of prestige. In around 1350 AD the Great Enclosure of finely dressed stone was built. This huge elliptical structure with its mysterious platform and conical tower is thought to be the royal court. There is no indication that the walls were defensive. This was a regime confident in its power and authority.

Peter Garlake’s reconstruction of the Great Enclosure Platform from Life at Great Zimbabwe, Mambo Press 1982

Then why did the city decline?

There are various explanations: the people had let their herds overgraze the land; they had cut down all the trees; there was a prolonged period of drought as may happen in southern Africa. But somehow none of these theories quite explain why, after 350 flourishing years, a community of perhaps 20,000-plus people should simply pack up and leave. Did all these farmers, herders, miners, craftspeople, soldiers, traders, accountants, court personnel and the city’s rulers leave on a single day, or did the city die slowly? The archaeological evidence does not say.

But we do know there were disruptive external forces. In the 15th century the Portuguese invaded the Swahili coastal city of Sofala. They were on the hunt for gold and so pressed inland with Swahili guides. Their interfering presence drove the trading routes north, giving rise to the Mutapa state. This new state may well have been founded by people from Great Zimbabwe. Certainly by the time the Swahili traders were coming up the Zambezi to trade with the Shona directly, the old trade route through Great Zimbabwe was no longer used. At this time, too, we see the beginning of another Shona city state: the construction of the stone city at Khami near Bulawayo in southwest Zimbabwe. In the following centuries this became the centre of the Torwa-Rozvi state whose other major cities during the 16th and 17th centuries included Naletale and Danangombe.

And so into history…

Of course with the Portuguese incursions comes the first documentary evidence. From the early 1500s Zimbabwe’s royal courts enter the historic record in the accounts of the Portuguese conquistadores. In 1506 Diogo de Alcacova writes to his king, describing a city of the Mutapa state

“called Zimbany…which is big and where the king always lives.” His houses are “of stone and clay and very large and on one level.” Within the kingdom there are “many very large towns and many other villages.”

The Portuguese historian Faria y Sousa also describes the King of Mutapa’s great retinue which included the governor of the client kingdoms, the commander-general of the army, the court steward, the magician and the apothecary, the head musician “who had many under him and who was a great lord”. Also noted were the vast territories over which the king ruled, the revenues and subject kingdoms of the king’s several queens.

And suddenly we have a true glimpse of what this land called Zimbabwe might have looked like in the past, a bustling, mercantile, metropolitan culture, supported by gold miners, farmers, cattle herders and craftspeople. And so it remained until well into the 18th century, albeit with a shift of Shona power to the southwest and the Torwa-Ruzvi state as the Portuguese presence caused increasing instability. Then in the 19th century came new invaders – the Nguni, the Ndebele and the British.

This centuries’ old heritage of royal courts is not a picture that the likes of Cecil Rhodes or, the later Rhodesian government of Ian Smith ever wanted anyone to see. And so in the end this is not so much a story of a city abandoned by its people, but of a people wilfully excluded from their past. In 1980 when Zimbabwe became an independent state, some of this past was reclaimed: the new state took its name from the first great Shona city, and adopted for its flag and coat of arms, an image of one of the city’s ceremonial soapstone birds. These are small steps forward, but there is still a long way to go before the world sees the indigenous histories of the Africa continent in their true perspective, or acknowledges their intrinsic cultural worth.

References: The classic work on the excavations of the city is Peter Garlake’s Great Zimbabwe 1973. For an overview of the mazimbabwe culture see Innocent Pikirayi’s The Zimbabwe Culture Alta Mira Press 2001. For a broader historical perspective Randall L. Pouwels The African and Middle Eastern World, 600-1500 Oxford University Press.