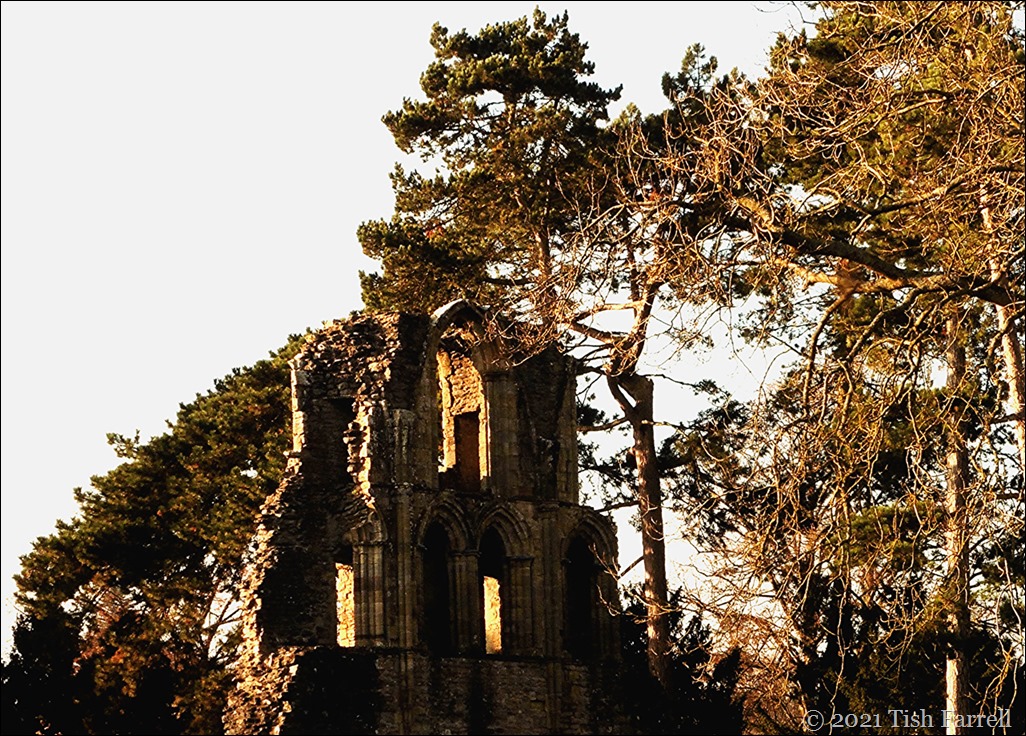

…that he built a grand palace to please his queen.

And that man would be Robert Dudley, first earl of Leicester (1532-1588), and his queen, Elizabeth Tudor (1533-1603). The royal apartment in question is known as the Leicester Building, part of Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire. Dudley’s own private chambers apparently adjoined the queen’s, so providing further substance to rumours that began on Elizabeth’s succession in 1558 (and have endured for more than 400 years), that she and Dudley were lovers.

Dudley was without doubt a royal favourite, and queenly predilection did indeed confer on him great wealth and courtly status. But he was also a man of considerable ability as well as good looks. In fact the Spanish ambassador reported home that he was among the three men who ruled the country.

He was already married when Elizabeth came to the throne. He had married Amy Robsart in 1550 when they were both seventeen years old and in what was said to be a love match. But by 1558, with Robert appointed Master of the Horse, a position that dictated almost constant attendance on the queen, Amy was reduced to a nomadic existence, living with friends and rarely seeing her husband. Finally she settled at Cumnor Place near Oxford, living in a private apartment in the home of the Forster family. But by September 1560 she was dead, having apparently fallen down some steps. Her neck was broken.

There was a colossal scandal, much enjoyed by Robert Dudley’s rivals and enemies. And although Dudley was cleared of any wrong doing (he was attending on the queen at the time), the whispers of an ‘arranged death’ never went away.

So now Dudley was free, but gravely compromised. Did he really think there was ever a chance to marry Elizabeth?

The new Kenilworth apartments were built in time for the queen’s third visit there in 1572, constructed in the latest elegant Tudor style. They were further improved for a fourth visit in 1575, so much so that Elizabeth extended her sojourn for an unprecedented 19 days, being marvellously entertained with fireworks, masques, hunts and a brand new pleasure garden created especially for her.

It is usually suggested that all this vast investment on Dudley’s part was his last ditch attempt to win the queen’s hand.

Yet from 1568 to at least 1574 he was actually having an affair with a young widow, Lady Douglas Sheffield. She bore him a child, whom he acknowledged as his ‘base son’ Robert Dudley, and thereafter took good care of him, although he was careful, too, to inform Douglas Sheffield that he could not marry her, fearing the loss of the queen’s favour.

Yet as time went on, he grew ever more anxious about the lack of a legitimate heir. And so in 1578 he secretly married Lettice Knollys, Countess of Essex, another widow with whom he was rumoured to have been having an affair before her husband’s death in 1576. The queen was furious when informed of the deed by Dudley’s enemies, and she banished Lettice from court. But it was around this time, with Elizabeth in her mid-to-late forties, that the so-called Phoenix Portrait was commissioned. (My photo was confounded by the gallery lights at Compton Verney where the picture now hangs, but you get the drift):

Such portraits were always intended as PR exercises. Quite apart from the phoenix rising from the ashes symbolism, the proliferation of pearls is also said to convey a particular message, i.e. confirming Elizabeth’s well cultivated image as Virgin Queen. No marriage for her then. Even so, spite ruled, and seven years into Dudley’s marriage he said she was still being insulting about his wife and taking every opportunity to ‘withdraw any good from me.’

Nonetheless he went on to play considerable roles in affairs of state. Most notably in July 1588 as the Spanish Armada approached, he was appointed Lieutenant and Captain-General of the Queen’s Armies and Companies. When Elizabeth went to address the troops at Tilbury, and made that now most famous speech, he was walking at her side.

After the victory he was feted, spending the last weeks of his life dining with Elizabeth. But by then he was already ill. He died suddenly in September 1588, on his way to Buxton in Derbyshire, to take the baths. When Elizabeth heard, she locked herself in her apartment and Lord Burghley was forced to have the door broken down. At her own death in 1603 Dudley’s last letter to her, written before his departure for Buxton, was found in her beside treasure box.

Past Squares #1

Hurrah! Becky’s squares are back for the month of October – our favourite past squares reprised, or squares about the past.