In the last post I featured The Hurlers stone circles near the Cornish village of Minions on Bodmin Moor. Here they are again, if only a small segment. They date from the late Neolithic or Early Bronze Age, around 2,000 years BCE.

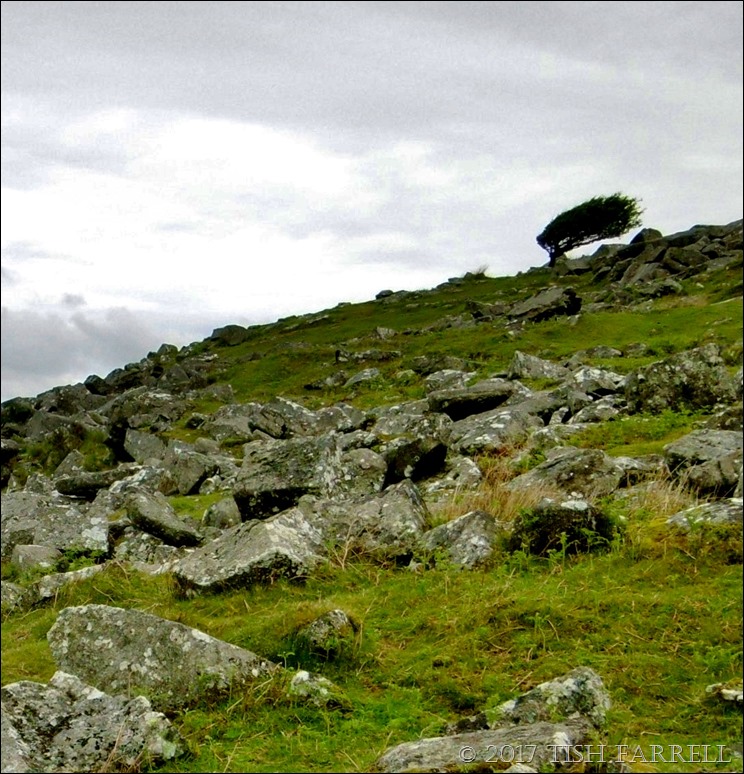

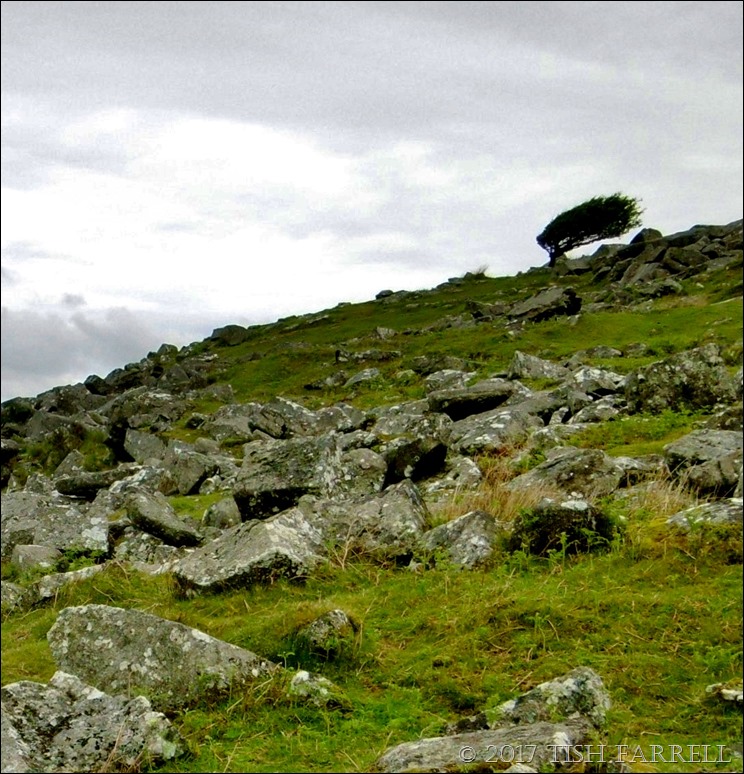

The landscape around is exposed and bleak, itself a product of the human intervention that began at least 6,000 years ago, when the first Neolithic farmers, equipped only with stone axes, began the systematic clearance of the forested uplands.

It is an arresting thought that, armed only with stone-based technology, we humans were already consciously rearranging the planet’s surface. Early farmers carried out shifting ‘slash and burn’ cultivation, clearing ground, then moving on to virgin territory when the farm plots lost fertility. By such means the earliest farmers cleared great swathes of forest right from one end of Europe to the other. On Bodmin, any chances of forest regeneration were then reduced by stock grazing, which through subsequent millennia finished what Neolithic communities had started, creating the windswept moorland we see today.

Of course these days we know that removing tree cover contributes to climate change and environmental degradation, by altering rainfall patterns, and accelerating soil erosion. But in this case global climate change was also a factor. During Neolithic-Early Bronze Age times it seems the climate was much warmer, with these uplands offering a more benign environment than today. A quick look at an ordnance survey map shows that Bodmin was a very busy place back then. There are numerous hut circles, burial cairns and tumuli, tor enclosures, stone-walled field systems, ceremonial stone circles and standing stones.

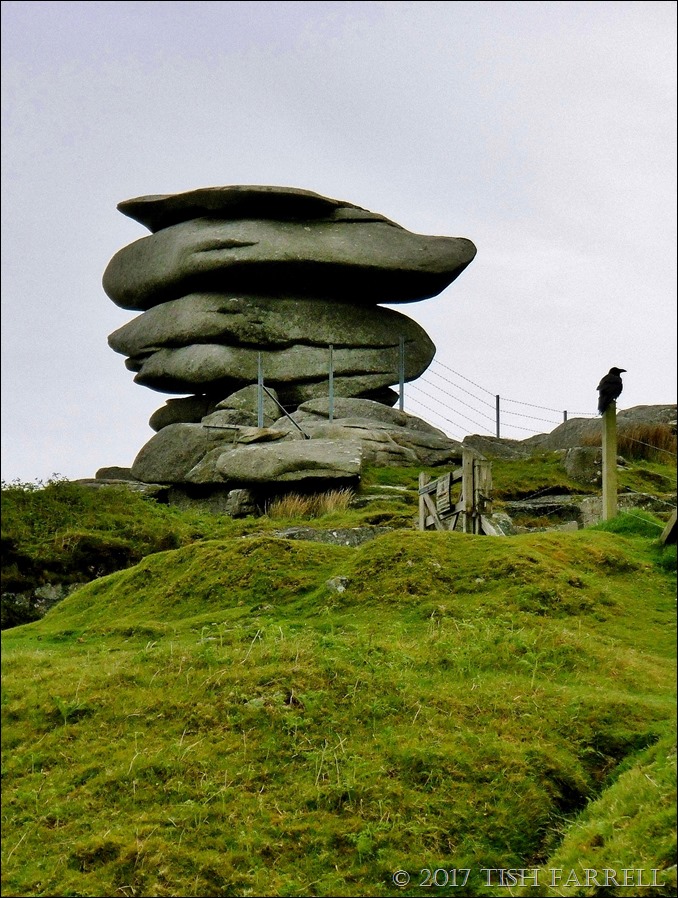

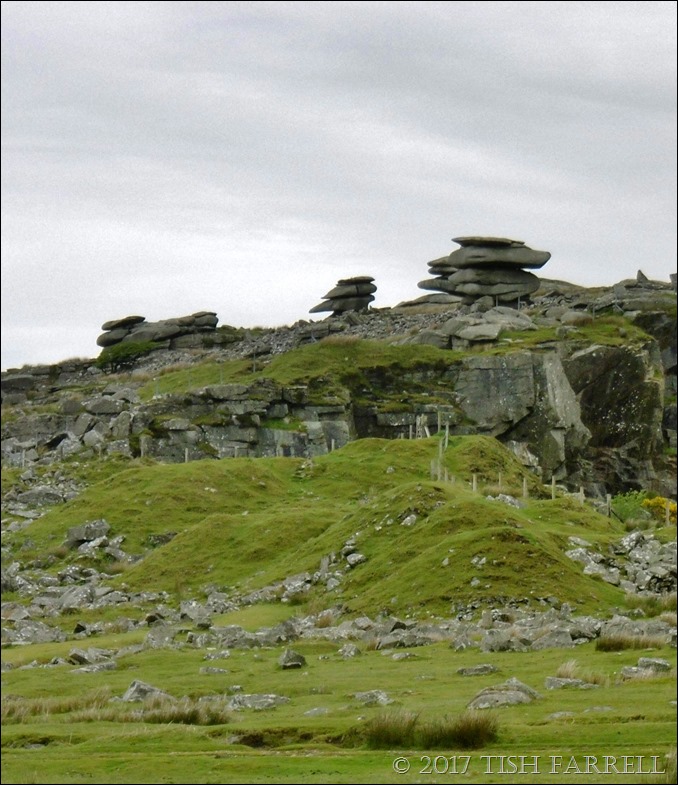

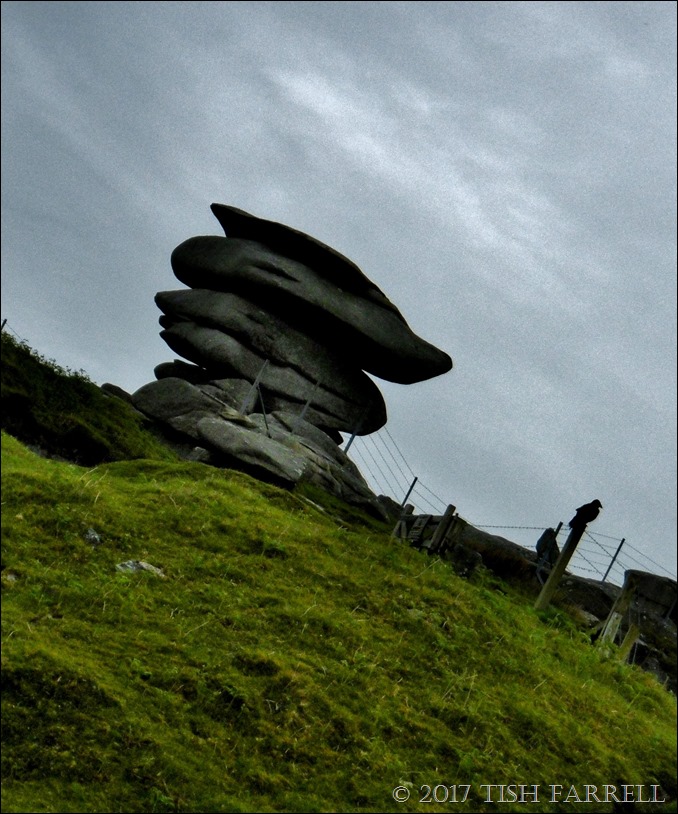

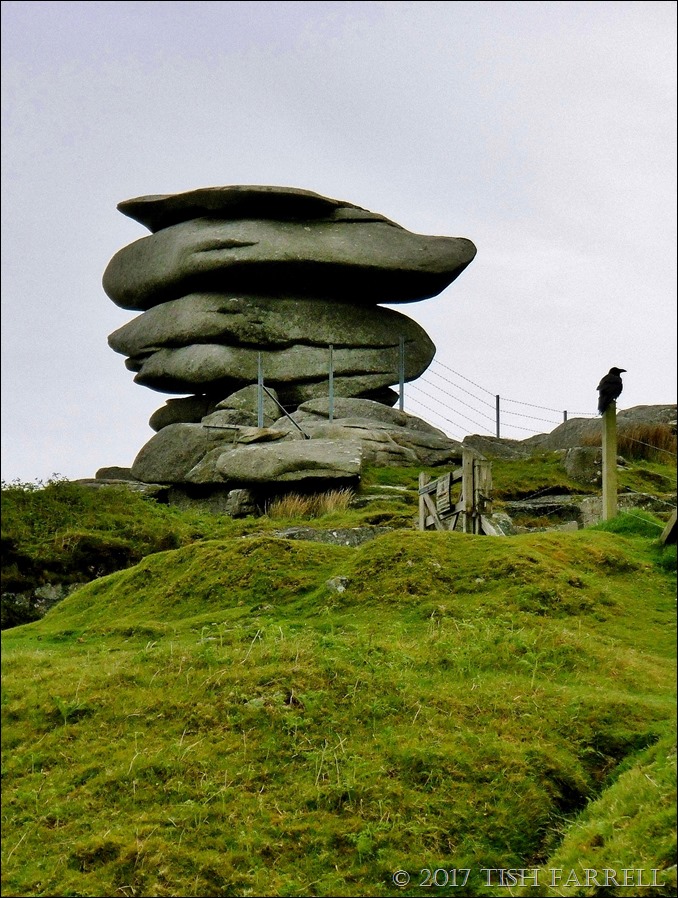

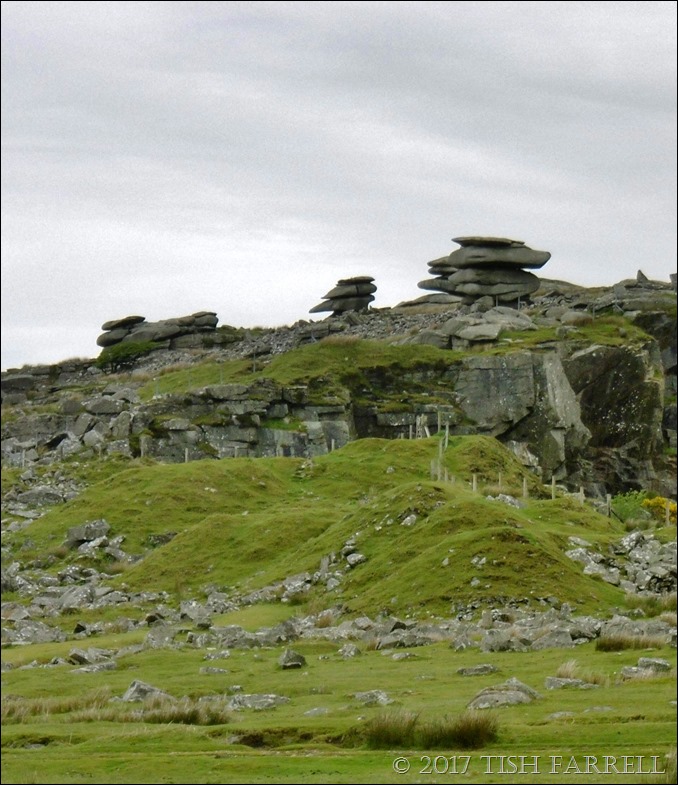

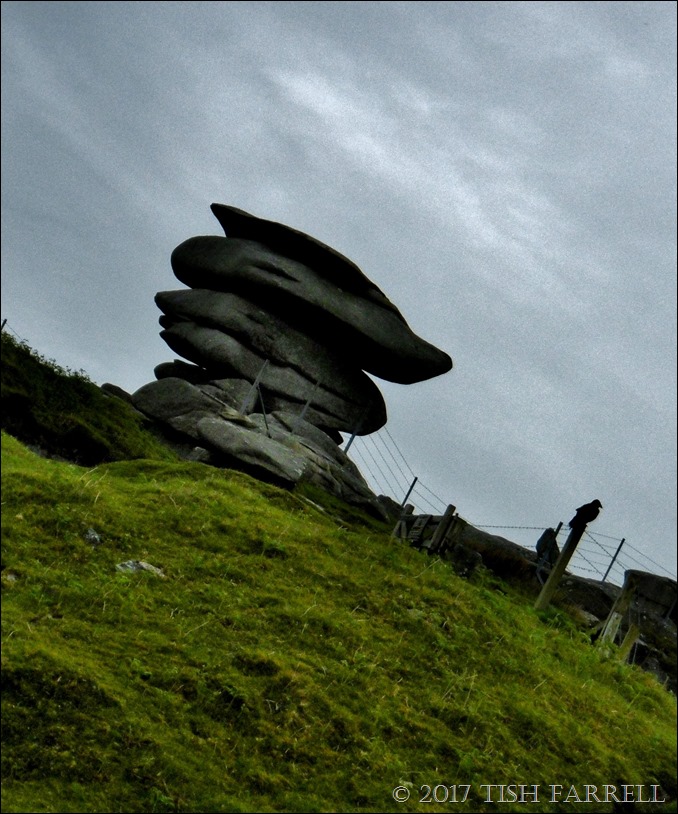

The siting of burial monuments, in particular, was very important – often on the skyline to be seen from one monument to another; or else related to a naturally prominent feature such as one of the stone tors. The Cheesewring Tor is a good example. It lies due north of The Hurlers circles. You will soon see why this weathered granitic pile of rocks captured the imagination of the ancestors, just as it captures ours today.

But there may also have been practical considerations too. When it came to the gathering of clans and families for important occasions, the visibility of man-made and natural features in a landscape without highways would have been the prehistoric equivalent of SatNav.

Looking southwest from the Cheesewring this is what you see on the skyline beyond the quarry: a series of round barrows:

But sometime around 2000 years BCE, the climate began to deteriorate and humanity moved to settle more low-lying areas. It is an interesting irony that the combination of human action and natural climate change which rendered the abandoned uplands unsuitable for anything other than grazing, thereby led to the survival of so many of the prehistoric remains.

Farming, though, is not the only agency of landscape change in this area. Shunt forward to the mid-nineteenth century and you will spot the evidence for quite a new kind of invasion. There’s a clue in that first photo of The Hurlers. Here’s another glimpse:

And closer still:

This is the Houseman’s engine house, part of South Phoenix Mine, now partially restored as the Minions Heritage Centre. It one of many such mines in the locality, their ruins as dramatic in their way as the stone circles and tors. For fifty years, between the 1840s-1890s, Minions was the centre of a booming copper mining industry. Over 3,000 people were employed here, including women and children.

Hundreds and thousands of tons of copper ore was extracted, and exported down to Liskeard and the coast at Looe by means of the ‘Cheesewring Railway’ otherwise known as the Liskeard & Caradon Railway. It was opened in 1844, operated initially by gravity and horsepower, and also carried granite and tin. You can just see part of the granite quarry below the Cheesewring tor. Other signs of Minions’ industrial heyday of miners, quarrymen and railway workers are the humps and bumps of abandoned spoil heaps. The nearby settlement of Minions is also evidence of the industry – it grew up around the junction of several branch lines to house the influx of workers. It is the highest village in Cornwall, and today has a rather desolate air.

And now for another kind of heritage: legend. There are all sorts of stories connected with Bodmin’s man-made and natural features. I mentioned the origin of The Hurlers in the last post. The Cheesewring tor has also inspired all manner of explanations. One story tells how it was created by Giants and Saints at the time in the early Dark Ages when Christianity was spreading through the land.

The Giants, who were used to tramping about their domain, and doing just what they pleased, were fed up with the Christian Saints invading their land, putting up stone crosses, and declaring all the wells holy. They called a council to decide how to rid Cornwall of the nuisance.

And to this council there dared to come the frail St. Tue. He challenged Uther, the strongest of the Giants, to a trial of strength. They would have a rock hurling contest.

Rock hurling was one of the Giants’ favourite pursuits. Also, seeing the slightness of Saint Tue, the Giants were sure they would win.

Saint and Giant thus then took turns to throw six very large quoit shaped rocks across Craddock Moor and onto Stowes Hill, but to Uther’s surprise the little Saint soon proved a formidable opponent. By the time the Giant came to throw his last rock, his strength was failing. To the sounds of much Giantly groaning, his stone tumbled from the pile. Tue then went to make his final throw. The rock was huge, but just as it seemed that the task was beyond him, an angel appeared and placed the rock on top of the pile. The Giants were so overawed by the sight of angel wings casting their golden glow about the place, they conceded to the Saints, and by this means Cornwall became a Christian land.

Another yarn has it that if you visit the Cheesewring at sunrise, you will see the top stone turn three times. This is more up my street myth-wise, and I truly would like to be there at dawn to see what happens, and also to hear the wind on the stones making them resound and mutter.

copyright 2017 Tish Farrell

Daily Post: Heritage

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

![779px-Rillaton_Cup[1] 779px-Rillaton_Cup[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/779px-rillaton_cup1_thumb.jpg?w=781&h=768)

![withprehistoricp00rout_0187[1] withprehistoricp00rout_0187[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/withprehistoricp00rout_01871_thumb.jpg?w=677&h=1275)