These glorious Nubian mats adorn my kitchen. They decorate our every day, their colours radiating like mini-suns however dull the weather. It is hard to imagine, then, that there is a dark tale behind their creation, a tale of statelessness and discrimination.

The makers of the mats are women from the Nubian community of Kibera, in Nairobi (Kenya). They, their parents and grandparents before them, were born in this quarter of the city suburbs. This has been the case since the early 1900s, when British colonial authorities gazetted an area of land for settlement by Sudanese Nubian soldiers of the British Army, men who had first been recruited during the 1890s when Britain was trying to establish control over the peoples and territories of East Africa.

This next photo thus shows another form of decoration – a Nubian KAR officer’s chest adorned with medals that attest to years of brave service in the cause of the British Empire.

![kenyas-nubians-officer-mw19-910[1] kenyas-nubians-officer-mw19-910[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/kenyas-nubians-officer-mw19-9101_thumb.jpg?w=504&h=701)

Copyright Kenya Nubian Council of Elders

This photo was taken in 1956, during the British colonial era. The officer is showing his invitation to a garden party at Nairobi’s Government House. The gathering was in honour of the visit to Kenya by HRH Princess Margaret of England (Kenya’s Nubians: Then and Now, Open Society Foundations).

*

The Nubian people (also known in the distant past as Kushites) have a long, long history, their homeland once stretching along the upper reaches of the River Nile in North Sudan and into southern Egypt. Much of their territory was taken in the 1960s for the building of the Aswan Dam by the Egyptians, and this was another cause of displacement. But way back in time, the Nubians were a people to be reckoned with. The earliest evidence of a metropolitan culture (the Kingdom of Kerma) has a date contemporary with neighbouring Ancient Egypt. Nubia was the gateway to the African hinterland, and a great trading nexus.

Dr Stuart Tyson Smith (University of California, Santa Barbara) says the Kerma culture “evolved out of the Neolithic around 2400 BC. The Kushite rulers of Kerma profited from the trading such luxury goods as gold, ivory, ebony, incense, and even live animals to the Egyptian Pharaohs. By 1650 BC, Kerma had become a densely occupied urban center overseeing a centralized state stretching from at least the 1st Cataract to the 4th, rivaling ancient Egypt. Kerma was sacked in c. 1500 BC, when the entire region was incorporated into the Egyptian New Kingdom empire.”

The Nubians and Egyptians traded, intermarried and warred with one another over many centuries, the Nubians finally ruling Egypt for half a century during the 25th dynasty (c. 750–655 B.C.E.) And though it may be a big surprise for some people to know this, there were Nubian, black African pharaohs, Nubian pyramids, and a Nubian form of hieroglyphics that were later developed into a 23-letter alphabet (yet to be deciphered). Clearly as time went on, Nubian culture was influenced by Ancient Egypt (though why not the other way around?), yet it also evolved in its own very characteristic ways.

The strikingly tall Nubian pyramids below were built at the time when Britain was a land of Iron Age farmers who lived in thatched round houses and constructed hill forts of earthen banks and ditches.

![Sudan_Meroe_Pyramids_30sep2005_2[1] Sudan_Meroe_Pyramids_30sep2005_2[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/sudan_meroe_pyramids_30sep2005_21_thumb.jpg?w=505&h=270)

Fabrizio Demartis Creative Commons

The Nubian Meriotic kingdom developed from the 25th Dynasty when Nubia ruled Ancient Egypt. It is named after its capital Meroë (begun c 800 BCE). Over 255 pyramids belonging to the Meroitic period have so far been discovered.

*

But back to more recent times, and the story behind my lovely mats. In World War 1, Sudanese Nubian forces were deployed in defence of British-ruled Kenya along the border with German controlled Tanganyika. This East African campaign was a brutal affair, fought over waterless, disease-ridden bush, as British forces attempted to thwart Count Von Lettow-Vorbeck’s ingenious guerrilla tactics, carried out by other Africans – the Count’s highly trained askaris from German East Africa (now Tanzania).

The British Army, with a few exceptions late in the war, did not allow the native peoples of Kenya to carry arms at this time, so it was the Nubians who were the main combatants. Kenyans were instead conscripted into the Carrier Corps to transport army provisions since mules and horses could not survive in tsetse infested bush country. Tens of thousands of young men died of starvation and disease in the British cause, their families often never hearing what had happened to their sons. They simply never returned from the war with Jerimani.

(For a vivid fictional version of this conflict see William Boyd’s An Ice-cream War).

In 1912 the British colonial administration in Nairobi gazetted 4,197 acres near the city for the settlement of Nubian soldiers and their families who could not be repatriated to Sudan. The Nubians called this place Kibra, the forest land.

![kenyas-nubians-family-formal-mw19-910[1] kenyas-nubians-family-formal-mw19-910[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/kenyas-nubians-family-formal-mw19-9101_thumb.jpg?w=524&h=380)

Nubian Family c1940s, photographer unknown. Copyright Kenya Nubian Council of Elders. For more wonderful photos see Kenya’s Nubians: Then and Now, Open Society Foundations

*

By this time, all British East African (Kenyan) tribes had been categorized, and the land they occupied, at the point of British incursion, designated as native reserves. Africans were not allowed to have title deeds to their own and and, in theory, European settlers (who did have title to vast acreages) were not allowed to encroach on the reserves.

The Nubians, however, were specifically categorized by colonial authorities as ‘Detribalized Natives’, and non-natives of British East Africa. This meant they could not claim any rights to have their land made into a reserve, nor could they build permanent structures on the land. The community, however, continued to provide further generations of soldiers who would serve in the King’s African Rifles.

During WW2 Nubian soldiers fought for Britain, alongside other black Kenyan recruits, in Somalia, Abyssinia and in the terrifying war against the Japanese in the jungles of Burma. It is another little remembered fact that the African troops of the King’s African Rifles played a determining role in the winning of the Burma campaign.

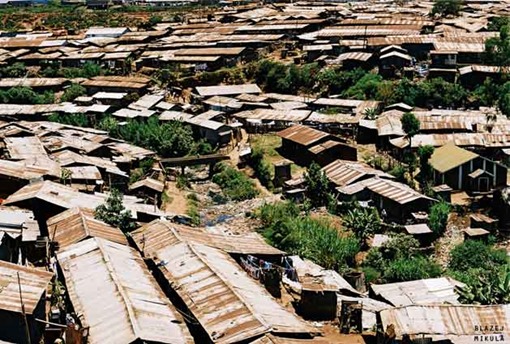

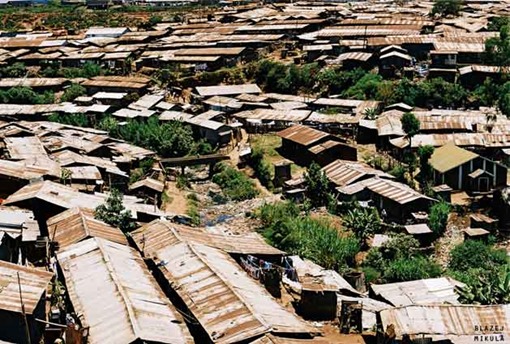

By 1955 the Nubian community of Kibra numbered 3,000. Back then it was an attractive rural village, the houses surrounded by large gardens. But in successive decades as Nairobi grew into a city, hundreds of thousands of rural Kenyans, seeking work, invaded Kibra, putting up shanty dwellings. Kibera, as it is currently known, is now one of the biggest slums in Africa.

A cropped image of Kibera, Nairobi. Photo CC 2014 Schreibkraft

Photo: CC Blazej Mikula

*

During colonial times, Kibra land remained the property of the British Crown. At Independence in 1963, ownership of Crown Land passed to the new government, and so became state-owned land. The new state also inherited an administration that was still largely operating under State of Emergency regulations from the 1950s Mau Mau uprising. Being able to prove who your tribe was and the associated right to domicile were essential proofs of citizenship. The Nubians’ former colonial categorization denied them on both fronts.

From 1963 until 2009, when the Nubian community in Kenya was finally accorded official existence as a Kenyan tribe, the Nubians of Kibera and elsewhere in Kenya had been stateless. While the colonial generation did have identity cards, the post-independence generations could only acquire them, if at all, with great difficulty, and after many years of persistence.

This meant they could not be formally employed, open bank accounts, acquire title deeds, participate in the affairs of their country of birth, vote, or even leave their own homes safely, since to be caught without an identity card is a criminal offence. The only opportunities to earn a living were in the informal sector, and for women, this included/still includes making baskets for sale through non-governmental trading operations, and Nairobi’s tourist curio shops. Hopefully now, with official recognition, the fortunes of the Nubian people will change for the better, but there is still much ground to make up, and in all senses. For more of these people’s story see the excellent short videos below, and also the full length BBC programme about Ancient Nubia at the end.

In the meantime, back to the beautiful baskets, and a Nubian woman at work. The method of construction involves coiling lengths of papyrus stems or dried grasses then wrapping them round with coloured and natural palm leaf strips. Truly great works of decorative art, and not only that, but life-enhancingly useful too. Expressions of spirit undaunted despite lives of grave hardship unimaginable to most of us?

![A-Nubian-woman[1] A-Nubian-woman[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/a-nubian-woman1_thumb.jpg?w=486&h=424)

Photo: http://in2eastafrica.net/home-stays-growing-ugandas-tourism/

Article on Nubians of Uganda: Flavia Lanyero 2011 Daily Monitor

*

text copyright 2014 Tish Farrell

Greg Constanine’s video explains the Kenyan Nubian dilemma

This brief film explains the history of Nubian statelessness in Kenya

Recent archaeological discoveries of the ‘lost’ Nubian civilization

Ailsa’s Challenge: Decoration – Go here for more bloggers’ decorative posts

![kenyas-nubians-officer-mw19-910[1] kenyas-nubians-officer-mw19-910[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/kenyas-nubians-officer-mw19-9101_thumb.jpg?w=504&h=701)

![Sudan_Meroe_Pyramids_30sep2005_2[1] Sudan_Meroe_Pyramids_30sep2005_2[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/sudan_meroe_pyramids_30sep2005_21_thumb.jpg?w=505&h=270)

![kenyas-nubians-family-formal-mw19-910[1] kenyas-nubians-family-formal-mw19-910[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/kenyas-nubians-family-formal-mw19-9101_thumb.jpg?w=524&h=380)

![A-Nubian-woman[1] A-Nubian-woman[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/a-nubian-woman1_thumb.jpg?w=486&h=424)