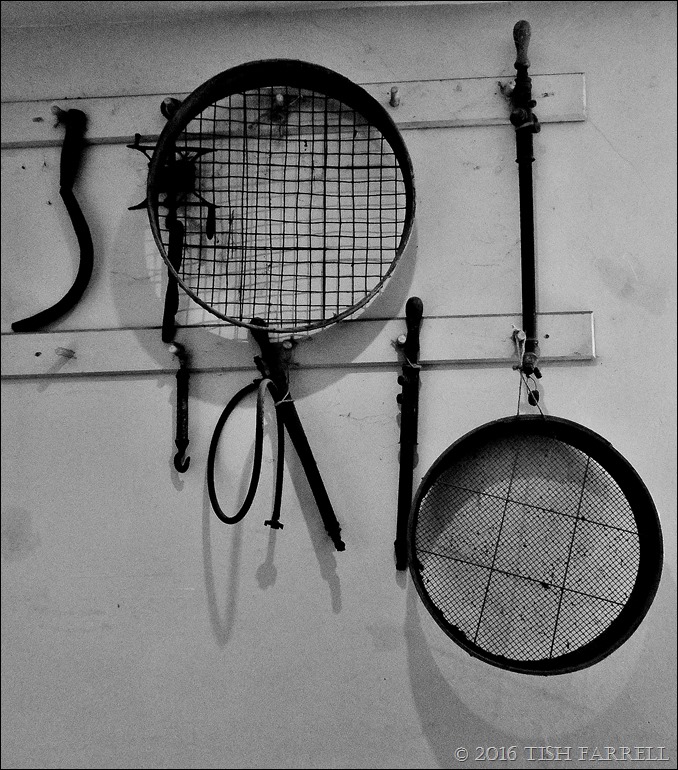

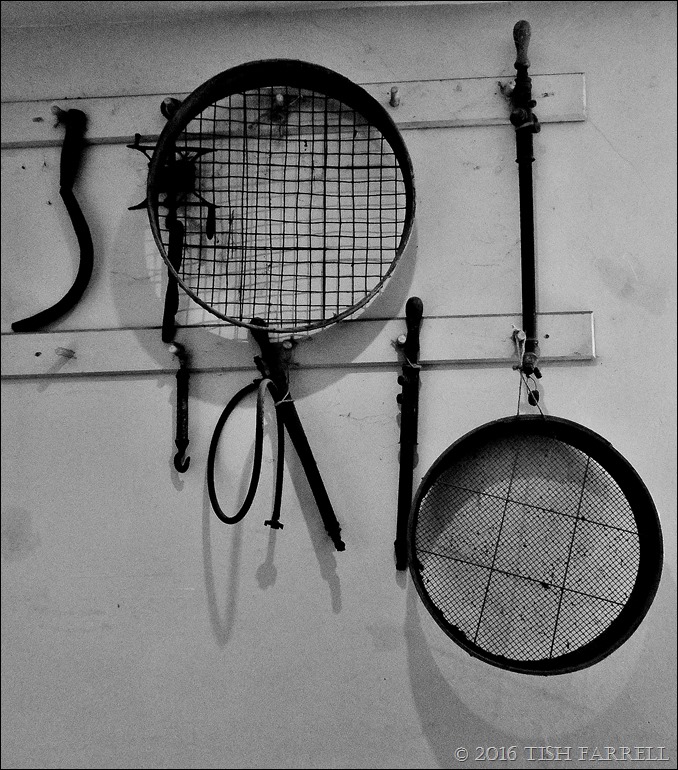

I hasten to say these are not my grandfather’s actual tools, but when I spotted this gardening paraphernalia in the gardeners’ bothy in the walled garden at Attingham Park yesterday, I instantly thought of Charlie Ashford. He was head gardener at Redhurst Manor in Surrey from around 1921. I have written about him in the Tales from the Walled Garden. The links are at the end.

Attingham is one of Shropshire’s grandest stately homes, once home of the Berwick family, but now in the care of the National Trust. I did have photos of the house, taken on an earlier visit, but the computer seems to have eaten them, and yesterday the walled garden was my only objective. There has been a monumental restoration project going on there since 2008, and this was our first visit. (Always the same with places on the doorstep.)

I think this is probably the hugest walled garden I have ever seen, and I truly cannot imagine why one household would need to produce quite so much food for itself even if it did include feeding all the servants. Here is one corner:

And yes, it was perverse to chose December for our first visit – a time when there is hardly anything growing. However, I was very taken with the climbing bean frames, just visible towards the back wall. Here’s a better view. I think they’re made from hazel whips. Ideal for sweet peas too.

The path around them leads to an adjoining much smaller walled garden. This is where we found the gardeners’ bothy, cold frames and glass houses, hot beds and hot walls – the kind of territory wherein my grandfather spent much of his working life:

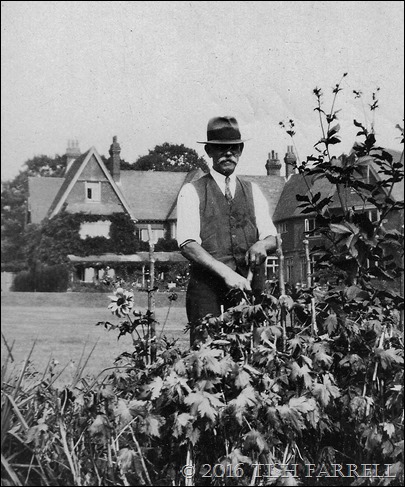

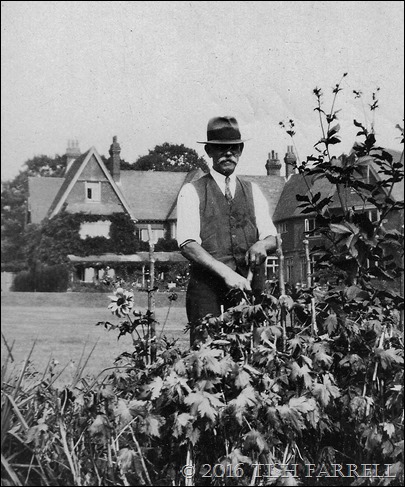

Charlie Ashford served his apprenticeship in an establishment as grand as Attingham. The position of head gardener was akin to the role of butler within the house. The training was long and there was a strict hierarchy of under-gardeners and garden boys. Redhurst, though, was a much less grand affair – a modest country manor by comparison. You can see it in the background in the next photo – grandfather in the dahlia and delphinium bed.

And here’s a glimpse of his working life from one of the talks his daughter, my Aunt Evelyn, gave to her gardening club. She was born in the gardener’s cottage at Redhurst and spent her earliest years in the garden there. I’ve posted excerpts before, but this is a longer version:

Imagine that we are standing in the holy of holies, my father’s potting shed. It was not all that large and the space was taken up with deep shelving on three sides of the shed. There was a door into the kitchen yard and another into the garden itself. On the back of one door were three large coat hooks to take the jackets that my father needed and also his green baize apron. On the other door hung his clean alpaca jacket which was worn when he went into the house, a dust coat to be used in the fruit room and his leather pruning apron with its thick, left-handed coarse leather glove sticking out of the pocket. These garments comprised his head gardener’s uniform; there was almost a ritual about putting them on for the various tasks.

My father’s own tools were hung in neat and spotless order on hooks to the left of the garden door. He insisted on clean tools and, after every task, the men had to be sure to wash, and then rub dry on old sacking any tool that had got even the slightest bit dirty. A little spot of oil was rubbed into the spades and trowels and forks until the metal shone. Wooden handles were treated with linseed oil which was thoroughly worked in. Only then could the tools be stored away. That is why probably to this day I am still using a well worn spade and fork that belonged to my father. There have been times when, if in a hurry I have hung my spade up dirty, I have gone scurrying back to give it at list ‘a lick and a promise’. I can almost hear my father saying, ‘That won’t do, miss. Dirty tools make bad workmen.’

The potting shed was filled with a wonderful mixture of smells of the sort you find in a ‘20s hardware store. Tarred string was the main one. Then there was the strange jungly smell of the raffia hanks hanging on the door. It suggested faraway places. There was bone meal, fish meal, sulphate of ammonia, Clays fertilizer, Fullers Earth, Hoof and Horn – everything to help bring in good crops – and all stored in wooden bins with brass bands and rivets and a wooden bushel or half-bushel measure on top.

*

There was the annual ritual of sowing seeds for vegetables, preparing the asparagus beds, pruning and shaping the fruit trees, getting the cold frames ready, going over the tennis courts to prepare them for the summer season. There would be glass to replace in the long glass-houses or hot houses. The herbaceous beds required a lot of work in autumn: overgrown plant clumps to be carefully split and replanted, all to be mulched with well rotted manure from the stable yard, or a sweeter mixture of well rotted compost and peat for plants that did not like manure.

Wages were low, and hours were very long, but there were seldom any complaints. Early in the year one man would be set the task of planting out young tomato plants in one section of the glass house. In another section another worker might be potting up seedling chrysanthemums. And so the cycle of work went on.

Dad had his own specialist greenhouse in which he grew plants for the house. Primulas were a particular speciality but he was careful to see that whichever of his men was put to work here that he was not allergic to the plants. Primulas can secrete a substance from the leaves that causes a painful and persistent rash not unlike shingles.

The kitchen garden was walled on three sides by a wall at least eight feet high. On the south side was some rustic fencing over which climbed roses, clematis and honeysuckle – all in a tumbling profusion that looked natural, but was carefully managed throughout the year.

Much of the equipment that the men used was made on the estate. There were sturdy wooden wheelbarrows made in the wood yard behind the stables. The wheels turning at a touch with never a squeak allowed. On busy grass cutting days an extra section fitted onto the top of the largest barrows so that the men could trundle the piles of cut grass away to the ‘frame yard’ to be spread on compost heaps there. Here there was also a long low open shed in which all the mowers were kept: a hand mower for paths and border edges; a small motor mower for the terraces and the little lawn areas; a large sit-on mower for the long stretches of lawn and the rough grass places; and a huge wide mower with a heavy roller, which a horse from the home farm used to pull across the beautifully kept lawn at the front of the house.

Cucumbers were also grown in the cold frames and never cheek by jowl with tomatoes in the hot house. It was a job for two men getting the frames ready early in spring. The frames were built of brick with solid wooden supports or runners to hold the strongly built wooden lights. When I was older I could just about help my father to open or shut the frames. It was important to keep the cucumbers at just the right heat and to give them sufficient ventilation. Grown like this they always tasted succulent. This was not surprising as they were grown in a deep, deep bed of well rotted stable manure mixed with peat and compost and leaves – anything to make the mixture ‘hot’.

Thinking back on the work done in those gardens everything had its use and nothing was wasted – especially time.

At the big house, it was important that gardeners should maintain a succession of lovely flowers – all year if possible, and especially those with scents. As soon as anything special bloomed, like Winter Jasmine or Viburnum fragrans, a spray or two went into the house early in the morning for madam’s breakfast tray, or the desk in the Major’s study. This was quite a ritual. Into the house we would go, but not into kitchen because that was Cook’s domain. We go around the house and in through a side door and into the Butler’s Pantry. Here Johnny the Butler ruled supreme. When we arrived with Dad’s offering for the day, the exchange would go something like this.

“What have got today then, Charlie? Do you want two silver holders or one cut glass?”

“Oh, I think two silvers, please, Johnny. I’ve got some fine sprays of Winter Jasmine.”

Then Dad would take the delicate sprays from the shallow basket that he always used and arranged them in the vases with great artistry. Thanks for such offerings reached him without fail: “Please tell Ashford that the flowers were just what madam likes. The colours matched her dress today.”

Evelyn Ashford Gibbings

Tales from the walled garden

Tales from the walled garden ~ back to the potting shed

Tales from the walled garden ~ when Alice met Charlie

Tales from the walled garden ~ more about Alice

*

Black & White Sunday ~ Traces of the Past