“Begin at the beginning,” the King said, very gravely, “and go on till you come to the end: then stop.” Lewis Carroll Alice in Wonderland

*

I sometimes feel I know too much about the process of fiction writing; I’d like to unknow it, and begin again from scratch. Sometimes I think I don’t know enough, and will never make it over that learning-curve hump. In between these two positions, there is also the problem of having taken in too much ‘how to’; the ensuing overburden of advice that can make for self-consciousness, and lead to an unappealing tendency to manipulate characters and events in ways that lack integrity.

The narrative content becomes inauthentic. Untruthful. You see it a lot in book-packaged series for children, the kinds of titles that are written by a host of poorly paid writers under the name of a pretend author whose persona has been created by the packager. (I worked on one of those deals once, but you won’t see my name on the Harper Collins title).

But then isn’t that the point of fiction, that it’s fictional; not real; make believe; just a story.

Well yes and no. Mostly no, I find.

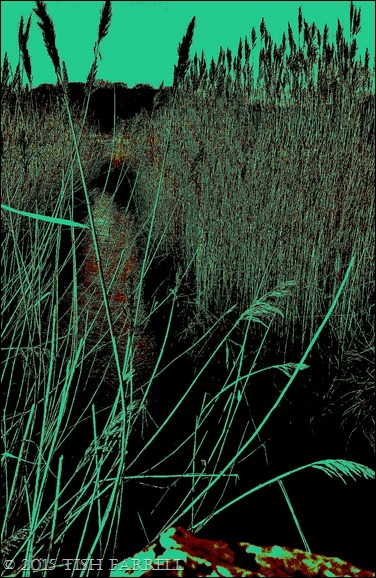

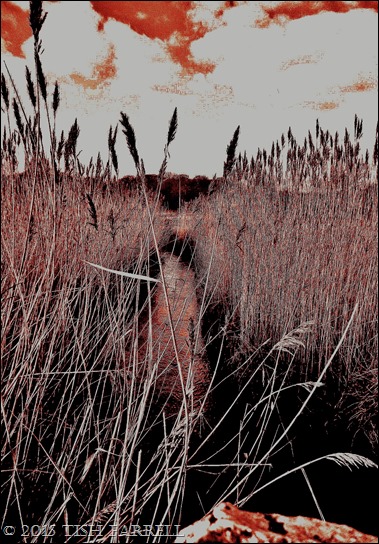

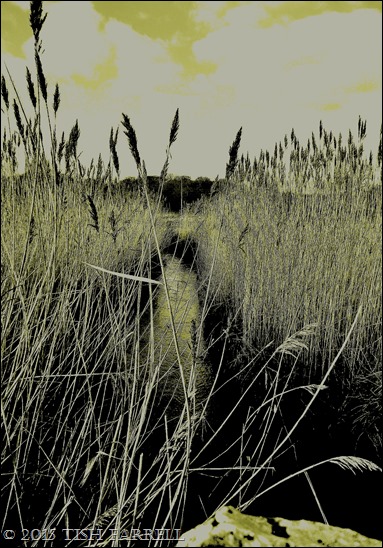

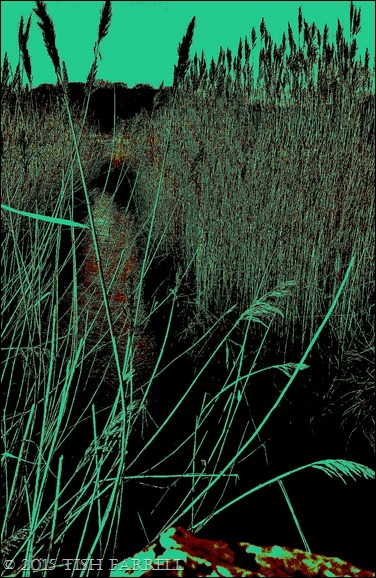

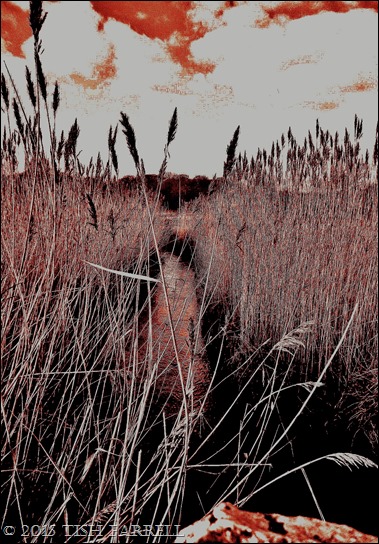

Perhaps this photograph might help to unravel the paradox. I will do as the King of Hearts commands, and begin at the beginning: the laying of a story’s foundations.

In any good opening you are quickly introduced to the protagonist(s). In the photo let’s suppose the main characters are the marsh grasses in the foreground. The eye is drawn to them; they are the most obviously defined; they stand out from the crowd. There is also something particular about their disposition, their relationship to/place within their setting which adds to their interest. At this stage we do not yet know them, but they have attracted our attention and we want to know more.

Along with meeting the story’s protagonists, and in accordance with the usual conventions of storytelling, the reader will, either immediately, or very soon, become aware of some conflict affecting them. Trouble is brewing, or has just descended.

The ‘trouble’ can come in many forms and moods from gritty realism to high comedy. In the photo it might be represented by the soft focus rock in the foreground. We can see it is a rock, but only the top of it is looming. In other words, we sense the imminent drama, but we don’t altogether know what form it will take, or the full implications for the protagonist. Now we’re hooked: we want to know what is going to happen, and in particular how the characters we have glimpsed will confront and resolve their difficulties.

To use another kind of image, then, these elements are the storyteller’s warp and weft. They are key to the construction process, but they are not the actual story. What is needed is substance and texture, the interweaving of details that will give life to the story’s characters and their situations.

This all about creating an internally convincing context, a believable world, a setting within which its inhabitants and their preoccupations articulate authentically. Everything must ring true.

And when a storyteller succeeds on all these fronts, then the fiction does indeed become a kind of truth. This is what Stephen King means when he says a story is a ‘found thing’. The storytelling process is about discovering something that already exists. In this sense, it is not ‘made up’. I think the analogy King gives is the retrieving of a fossil from its rocky matrix; how good a specimen you end up with depends on the quality of your excavation techniques and your understanding of the materials involved. You also need a steady hand, and a sharp eye.

Looking again at the photo, the stream, the marsh, the distant wood and the sky are all part of the context for the foreground grasses and rock. They are the setting. The wood adds depth of field and also a sense of mystery. It contrasts coldly with the pale sky. Perhaps, after all, the trouble is coming from that direction; the rock in clear sight is just a distraction, or only a foretaste of worse to come. Storytelling requires cycles of tension, building in intensity. The triple helix is a useful image to think of.

While we’re here, we might also imagine the stream as the narrative thread. No matter how the storyteller chooses to reveal the series of events that make up the story (and of course they need not be consecutive or chronological in the way that the King of Hearts demands of the White Rabbit) there must always be onward momentum, pressing the reader along, piquing their interest, not losing them on the journey.

This means creating a balance between revealing and withholding information – adding suspense or a new twist. And it’s at this point the storyteller needs to look out, and stay true to context and characters – no rampant extraneous invention and manipulation to create gratuitous excitement.

“A good story cannot be devised; it has to be distilled. ”

Raymond Chandler

This does not mean flat writing. Far from it. There must be light and shade, surprise, variety, and glorious detail (though not too much), yet all must arise naturally from within the story, have believable existence within the created story world. It is a form of alchemy. Or conjuring. Or mediumship, and the makings have their source deep within the storyteller’s subconscious.

The narrative that emerges is the result of dialogue between the subconscious and conscious mind. Although, just sometimes, the subconscious will do all the work. And it is then that the writer will say the story simply downloaded/was dictated to their inner ear, and all they did was type.

Of course all I have told you here is the ‘how’ of story, and not the ‘what’. And so where does the ‘what’ come from? All I can say is that any writer must find and stake out their ‘territory’, explore every inch, and command it the best they can, only then will the full story emerge.

Hilary Mantel’s muscular recreation of the Tudor world of Thomas Cromwell (Wolf Hall, Bring up the Bodies) is an excellent example. She has done her homework, and then she has conjured. Most of my own published short fiction has grown from years of living in, and reading about East Africa. A host of characters without stories lives in my head. The gathering process, the interrogation of data never stops. One day I will excavate the perfect fossil.

But before I leave this photo, I have to say that of course the actual story is not about the upfront grasses or the rock. There is someone in the foreground who does not appear in the shot. A dark-haired girl. I think her name is Eirwen and she has come to the seashore to gather the marsh grasses for thatching. As she cuts the sheaves, she is thinking of Ifor, the seer’s son, and if he will come as promised. She is sad because he won’t, and thrilled because he will. Then a cry of a heron makes her look towards the sea. A fleet of dark ships is heading ashore. She sees the glint of iron – shields, spears, men on horseback leaping into the shallows. The cry of the heron becomes her cry…

© 2015 Tish Farrell

Related: Also see my post about creating setting/world building at Knowing Your Place

This post was inspired by Paula’s Black and White Sunday: Inspiration

*

Secrets, conspiracies, tragedy,

dark comedy – a fast-paced

novella of interwoven tales set

somewhere in East Africa

Available on ePub Bud

5* Amazon Kindle Review

When war comes it can rip your

family apart. Then you have to

decide whose side you are on.

Ransom Books Teen Quick Read