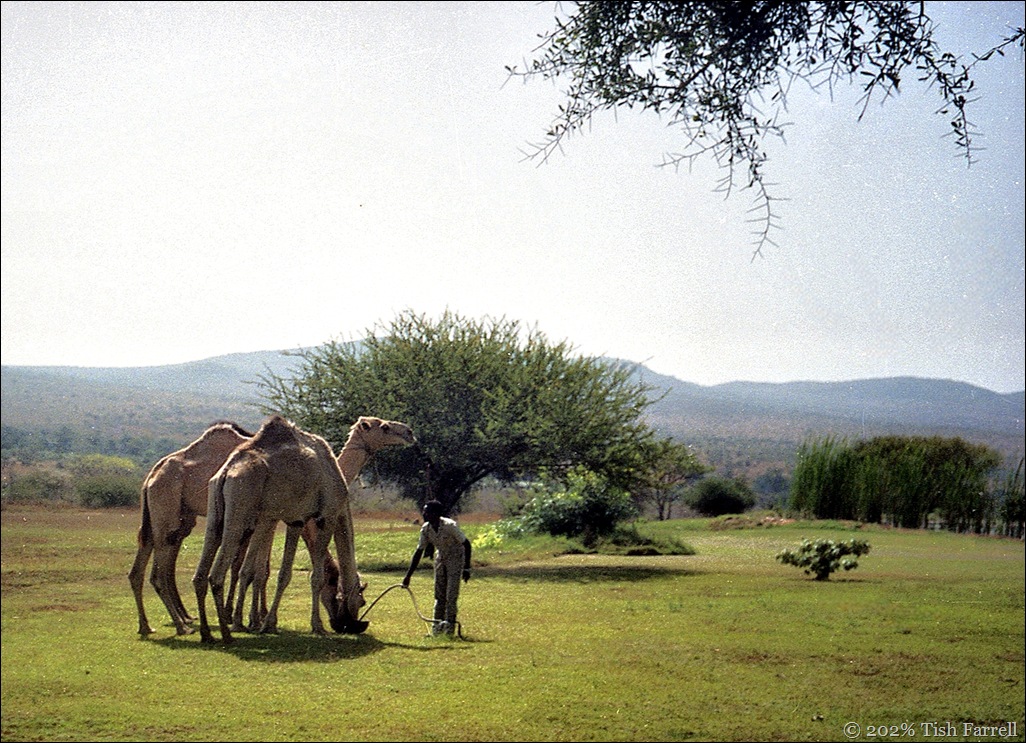

Maasai Mara with desert date tree

*

We’ve been living back in the UK since 2000, our years in Africa increasingly faraway. And yet…

And yet this spring and summer in Shropshire we’ve been very short on rain. The temperatures, too, have recently risen after a cold and windy spring. My gardening self grows anxious. Several times a day I do the rounds of my vegetable plots, checking on the kales, chard, beans and potatoes, the onions and leeks, examining the greenhouse tomatoes and cucumbers for signs of stress. My hands are always dirty, soil crushed under nails, as I prod the soil, testing for moisture levels around the plants.

It makes me think of Kenya days, pastoralists like the Maasai depending on rain to replenish the grasslands for grazing, cattle their life-blood in every sense; village farmers waiting for the November-December small rains for sowing; for the long rains March to May to bring the crops to harvest: lives and livelihoods dependent on monsoon weather systems that are nothing if not capricious.

Nor is this new. Oral history accounts, some going back two or more centuries, make reference to periods of drought and famine. One type of oral record is the memorized male circumcision list that survives in some communities. The rite was carried out every ten years or so, and the given year commemorated by some notable event. Food shortages were often inferred.

For instance the list for Maragoli in Western Kenya has 1760 as the time of Kgwambiti. Our Maragoli house steward, Sam, interpreted this as people behaving selfishly like animals, suggesting a food shortage. Likewise Vuzililili for the year 1800, a time when small insects fed on large insects. Then in 1900 Olololo-Lubwoni – refers to a time when jigger fleas (olololo) infested people’s feet, implying that that households were dusty and not swept properly. Lumbwoni is a very thin sweet potato, also suggesting drought and lean times.

Another remarkable source of rains failure evidence is the revised historical events calendar used in the enumerators’ guide to the 1969 Kenya census. At this time many rural householders would have been born in the 19th century, or else reckoned family chronology according to particular past occurrences. For semi-arid Ukambani, a drought-prone region in southern Kenya, it was generally agreed that there had been six significant periods of famine in the 19th century: Ngovo (1868); Ngeetele (1870); Kiasa (1878); Ndata (1880); Nzana (1883) and Ngomanisye or Muvunga (1898).

In the past, too, it transpired that the Akamba people had established emergency strategies via extended kinship allegiances. This involved moving from the worst stricken areas and, for a time, living with relatives who were not so badly affected, or who had their own water-holes. Rules of reciprocity of course applied; this was not charity.

It was important, too, that in pre-colonial times the Akamba had a sphere of far-flung connections through their hunting and trading activities, one that extended into what is now Tanzania. This increased the scope for finding sanctuary from drought-stricken regions, but of course was curtailed when the colonial administration consigned each ethnic group to a designated reserve, basically drawing a line around the territory that each community apparently occupied at the time when the British arrived; self-determination being duly cancelled by a line on a map.

But perhaps the most compelling evidence for the enduringly random state of weather across East Africa is the deeply embedded cultural phenomenon of the rainmaker. Every community had them; perhaps still does. They were often rich and powerful individuals. And contrary to what may be imagined, the forecast of rain was mostly based on informed careful observation of natural phenomena, including the movement of clouds, wind directions, dew formation, the behaviour of particular hygroscopic plants and trees that respond to rises in ground water, the arrival of particular species of birds and insects. Such observations informed planting decisions, the particular crops chosen, the times and places they were sown.

It’s tempting to think our Met Office could learn and thing or two.

And so I ponder again on our lack of rain. Our lives do not depend on the success of our garden produce. The Co-op’s daily deliveries of fresh food are two minutes’ walk from the house. I anyway have an outside tap and a clutch of watering cans. The water is always there. (Or at least it is for now). A luxury however you look at it. But even so, the daily sight of parched soil does seem to trigger some bred-in-the-bone alarm system, all those generations of farmers and gardeners in my family tree worrying…

And so the sky-watching continues, the hopeful eyeing up of every darkening cloud.

And probably also, in the not too distant future when the rain comes, there will be the ungrateful complaint that it doesn’t seem to know when to stop.

*

copyright 2025 Tish Farrell

Lens-Artists: Stormy This week Beth wants to see scenes of storminess.

![230_thumb[6] 230_thumb[6]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/230_thumb6_thumb.jpg?w=1026&h=677)

![Taita Hilton - safari vans come and go_thumb[5] Taita Hilton - safari vans come and go_thumb[5]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/taita-hilton-safari-vans-come-and-go_thumb5_thumb.jpg?w=1026&h=658)

![Taita Hilton - header _thumb[5] Taita Hilton - header _thumb[5]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/taita-hilton-header-_thumb5_thumb.jpg?w=1282&h=565)