Remains of Pentre Ifan chambered tomb, Newport, Pembrokeshire c. 3,500 BCE

*

We humans have problems with time: too much of it; not enough; the wrong kind for a planned action or pronouncement; then there’s ever that tale of elders who forget what they had for breakfast, but recall in minute detail events of decades past.

We try to pin it down of course, have long done so with all manner of devices. Most likely the late ‘Stone Age’ people who constructed Pentre Ifan above, had contrived the means to keep track of it. For instance, the placement of so-called standing stones, the particular configuration of megalithic circles, the siting of tomb entrances, whence to observe the movement of stars, the angle of the sun, and so know where they stood in relation to the earth’s perceived cycles. A time to plant; to make a journey; to hunt; to trade; mark seasons for rites and festivals.

Mitchell’s Fold Bronze Age stone circle, Shropshire-Powys border

*

We don’t know who these prehistoric (pre-literate) people were. There is no apparent connection between us and them. How do we even begin to grasp what five and half thousand years actually means. Most of us, unless we spring from some dynastic household that records family pedigrees down the centuries, or derive from some close knit community where little has changed for generations, cannot name our four pairs of great grandparents without the help of genealogy.com. We certainly have no true idea of how they lived day to day, unless they kindly left us their diaries; and even then…

As L.P. Hartley says in the opening of his novel The Go-Between: ‘The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.’ And for most of us, too, our generations of ancestors left no mark, but were ever caught up in ‘big people’s’ histories; the machinations of church and state.

*

There are anyway far bigger pasts than our human one. Here in my home county of Shropshire, in the borderland known as the Welsh Marches we have some of the planet’s oldest parts. Seven hundred million years old, in fact.

Set against such a monumentally unimaginable timescale, the history of humanity, including that of our primate ancestors, is not even a magnified dot on the horizon.

This is what Peter Toghill has to say about the Marches geology:

The beautiful landscape of the Welsh Marches

is underlain by a rock sequence representing ten of

the twelve recognised periods of geological time…

This remarkable variety, covering 700

million years of Earth history, has resulted from

the interplay of… (1) erosion and

faulting which have produced a very complex

outcrop pattern; (2) southern Britain’s position near

to plate boundaries through most of late

Precambrian and Phanerozoic time; and, most

importantly, (3) the incredible 12,000 km, 500

million year, journey of southern Britain across the

Earth’s surface from the southern hemisphere to

the northern, caused by plate tectonic processes.

An introduction to 700 million years of earth history in Shropshire and Herefordshire

*

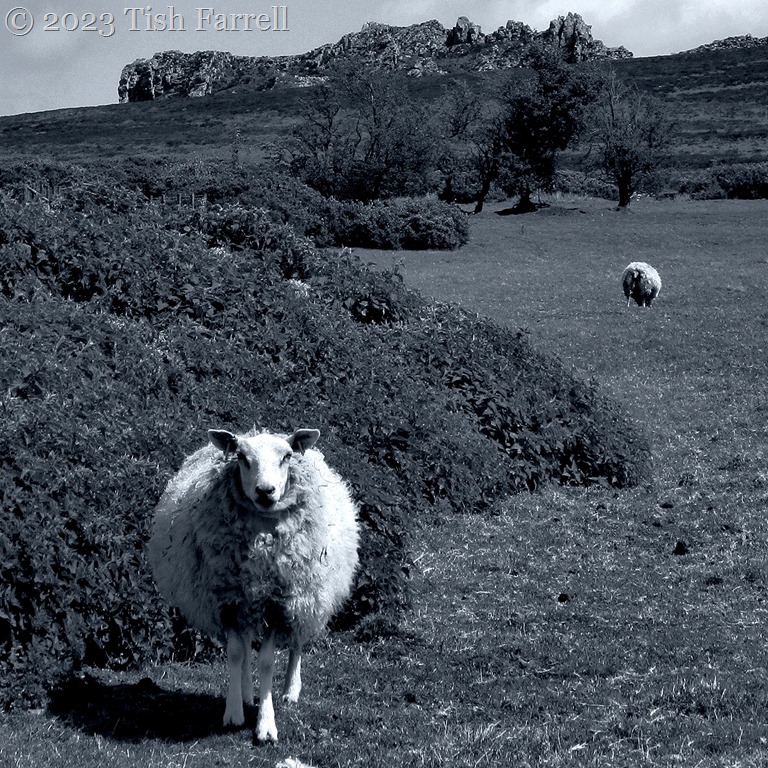

This distant view of the Stiperstones from Mitchell’s Fold stone circle, shows two of the Ice Age tors along the five mile summit, (Manstone the highest point on the left). This hill was probably formed from the laying down of quartzite sand when the whole of Southern England lay in the southern hemisphere, somewhere near the Comoros Islands in the Indian Ocean. That was around 500 million years ago, about the time when it began to move north. The tors themselves were exposed far more recently, by the repeated freezing and melting of glaciers that nudged up against them during the last Ice Age (115,000 to 12,000 years ago).

*

Makes me think we humans sometimes think too much of ourselves and what we think we have achieved. Maybe the planet has the edge on us by a few hundred million years. It’s certainly done some momentous shunting and shifting.