First published as El Nino and the Bomb, Cicada Magazine 2008, now a Kindle e-book

First published as El Nino and the Bomb, Cicada Magazine 2008, now a Kindle e-book

artwork: Kathleen Collins Howell

MONDAY

First light, Kimiti Farm, Ingigi

Kui wakes – a golden starburst in her head. When she opens her eyes the idea is there. She does not know where it comes from, but it seems to have something to do with Baba, her Daddy Julius, whom she rarely sees because he works in the city, far away from their village.

Thinking of Baba gives her a sickly, sinking feeling. Yesterday he came when she and Mummy were on their way to church. Kui spotted him first. There he was, so smart in his dark city suit, picking his way up the muddy lane. She wondered why he did not have on rubber boots as she and Mummy did, or carry a brolly since it had started to rain again. She wanted to run and hug him, but Mummy gripped her hand more tightly saying, ‘No, Kui. Stay under the umbrella. You will spoil your best clothes.’ And then Baba was there, standing over her, but before Kui could open her mouth to greet him, he and Mummy were face to face, and it was all stabbing words and hard eyes.

‘I am taking Kui to church,’ Mummy said, speaking the words in a way that gave Kui a crushing feeling in her chest. ‘We will return at supper time.’

Baba made a cross face. ‘You know what I think about that.’

Then Mummy said, ‘Yes, Julius. Your godless views are well known to me.’

That did it. Kui tried to twist her hand free and run back to the house, but Mummy’s hand gripped like iron claws. Next Baba was shouting, ‘For God’s sake, Faith. I’ve come to see you, don’t you understand? I’ve spent good money on fares and now you say you’re taking the child to wail and pray all day. Well dammit woman, I’m going to the pub.’ And he did too, striding off in the opposite direction towards the village shops. Kui watched him go, picturing him stepping inside Jimmy Mwangi’s bar where she knew many of the village men went on Sundays.

And so that was that. Baba had gone. No hello. No bye-bye. He did not even notice her new church dress that Granny had bought for her. For the rest of the day she kept thinking she had done something very bad. Pastor Benson’s loud shouting did not help. Sins came flocking round her head like swarms of biting flies, and the priest’s cries of Repent! Repent! sounded like curses.

When she and Mummy came home from church it was nearly night-time, and the rain had turned to a misty drizzle. While Mummy made their evening meal, Kui took Mummy’s big umbrella and went back to the farm gate to wait. In the growing darkness she heard the frogs in the hedgerows pipe louder and louder, and the crickets chatter like crazy, but Baba did not come. She and Mummy ate their ugali and greens alone as they usually did, and then Kui went to bed. For ages she lay very still in her little room, listening out for him. Then the songs of bugs and frogs filled up her head and she stopped listening.

It was the slamming house door that woke her. Then the rain came beating on the roof, and then there was a bad row with Mummy’s voice rising above the rain noise:

‘Drinking away Kui’s school fees again-

‘Treating the whole bar-

‘How can you be so irresponsible, Julius?

‘My God. Kui is five. She should be in school-’

At first Baba did not say much. Then he let out a roar that sounded just like Lois, Mzee Winston’s old cow, who often stood by their fence and bellowed like that when she was unhappy.

‘I’ll kill you, slut. Insulting me…your…your husband…how dare you-

‘Peasant. Whore–

‘How’d I know that child is mine?’

Then the fight really started and Kui had to wrap her head in the blanket to shut it out. The next time she woke there was only the pounding rain and blackness and Baba snoring loudly next door.

Now, though, there is light at her window and she is wide awake, the idea shining like the Wise Men’s star. She will go and live with Granny. Then she will never again wake up to find a stranger-ugly-Mummy leaning over her bed with swollen eyes and crusty blood on her lips. Also if she stays with Granny, Baba will stop hurting Mummy, and Mummy can come on the bus and visit her at Granny’s house.

Kui’s heart flutters like a small bird against her ribs. She must hurry. Already Jo-Jo the cockerel is crowing good morning on the shed roof. Any moment Mummy might come to help her dress. But she does not need help, does she? She is a big girl now. Soon she will be going to school. Granny will take her. She slips out of bed, shivering in her vest and pants, and quickly pulls on the church frock she was wearing yesterday. She cannot reach all the buttons, but never mind. Granny will say Ah! My little princess, as soon as she sees her. The pale blue satin is soft as silky sky and the net petticoats float like clouds around her legs. As she pulls on the long white socks and fastens the straps on the patent shoes she thinks she is just like Cinderella going to the prince’s ball. Then she spots the big pink cardigan on her shelf. Granny made it for her birthday, along with the matching bonnet with its big fluffy tassel. She puts them on.

Next she wonders how to leave the house. She can tell from Baba’s snoring that he is on the sofa by the front door. If she creeps by on tiptoe he will not wake, but she doesn’t want to smell his breath. She turns to the window. One bar of the thief-grille is broken. It is wide enough to squeeze through. She climbs onto her bed and opens the window, then hitching up her skirts, wriggles through, and climbs down onto the wooden bench outside. Pleased at her escape, she waves at Jo-Jo, puts her finger to lips (Ssssh), then jumps lightly into the mud that make ugly splashes up her socks. Oh dear. She rubs the stains worse, then skates off down the rain-soaked path. She is glad she has on her best church shoes instead of the ugly rubber boots. The slippy soles are good for mud-skating, and Mummy is not there to tell her off.

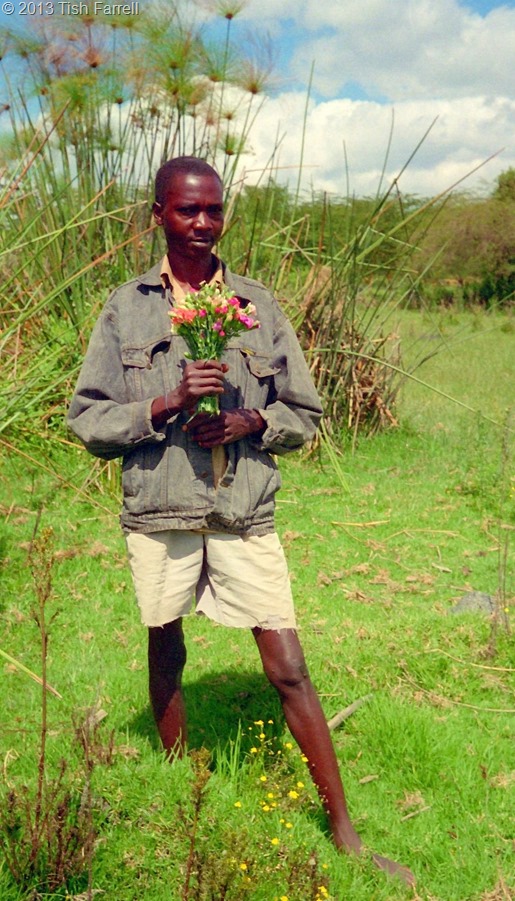

Out on the lane it is foggy, but the rain has gone. She passes no one, although there are some big boys climbing the mango tree outside Mzee Winston’s gate. Then down at the corner by the tea collecting shed she sees the minibus Joybringer taking on passengers. She knows it is Joybringer because it has golden rain round the back window and Mickey Mouse is waving to her. She also knows that this is the bus that she and Mummy take when they go to see Granny. While the tout is on the roof tying down a bicycle, she slips aboard, dodging between a mama with a basket of eggs and a man waiting to load a large iron roof sheet. She worms her way through the forest of legs and bundles to a corner space on the back seat.

She has no money for the fare, but she will tell the tout that Granny will pay when she gets off. Also, she is not sure which stage to ask for except that Granny always meets them at the big shopping centre past the coffee farm. Kui looks forward to that bit of the journey. The shop by the bus stop has beautiful pictures of black and white cows painted on its walls, and Mummy tells her that the pictures are there so everyone can know it is the butcher’s shop, even people like Kui who cannot read yet. Granny will be waiting by the cows, and when she sees Kui she will cry, ‘See what joy the Joybringer brings me’ and give Kui a big hug. Then they will go hand in hand down the windy track to Granny’s little wooden house, and Granny will stir the coals on her hearth of three rocks and make the special porridge that she always makes, and give Kui a big cup of milky, sweet tea from her thermos flask.

Kui licks her lips, then hugs herself with excitement as Joybringer speeds off through the village. How glad she is to be visiting Granny. How grown up she is to be travelling on a bus all by herself.

~

5.30 a.m. Kiarie Farm, Ingigi

Even as daylight sifts through the bedroom curtains, Winston Kiarie knows there is something wrong. The worry that has haunted him for weeks now roots like a jigger under a toenail. All night he has lain awake, listening and wondering – on and on, as the clock ticked off the hours. All night the rain has burst like gunfire on his iron roof, boiling out his gutters, threatening to explode expensive window glass. In the black hour before dawn, with Rahab snoring beside him, he finally understood the meaning of water on the brain. He had it. Lying there in his own bed, trapped like a man inside a waterfall – the drenching, drumming deluge. Where did such rain come from? Never in his long life had he known weather like it, the short rains becoming long rains, the long rains forgetting to stop.

Then the jigger-fear started up. ‘They’re unnatural,’ it nagged, ‘these rains they call El Niño. Now is the time of soft mists to ripen winter maize, not of flood and tempest to devastate the land. Mark my words. Some great evil is abroad.’

And in the darkness Winston found himself muttering, ‘Yes. Yes. It’s what I thought. Some even say it’s the end of the world.’ This thought made him tremble, and quickly he probed the dark for more rational explanations. Fear, he knew, always loomed largest at night. The jigger was probably exaggerating. By day its pronouncements might not seem so ominous.

Yet with the dawn Winston finds that the word ‘unnatural’ still running round his head. He watches the curtains lighten by degrees. Hears the rain stop hammering, but still the fear is there. Sighing, he hauls himself from the bed where Rahab still snores, gently tucks the blanket round her. Not even the jigger fears can put off the morning routine: a trip to the latrine, milking, then a big mug of tea.

Through the crack in the curtains he can see that all is greyness out in the yard. He struggles stiffly into pants, shirt and the bright blue pullover that Rahab made for him in the days when she could still conjure knitwear from two steel pins, a fat ball of yarn and some secret inner vision that he could never fathom. At the kitchen door he pulls on the old English sports coat, up-ends and shakes his rubber boots before putting them on (so clammy on bony old feet) then, unbolting the door, steps into the yard.

Outside, his hands fly skywards. Thank Ngai. No rain. Only wet mist, and that at least is seasonal. He slip-slides through farmyard mud, heading for the path to the long-drop latrine. In the slow-going he thinks that, at their age, he and Rahab could probably do with one of those modern indoor bathrooms that may be found in smart hotels. But then it would be costly to build, and the drainage hard to manage with the farmhouse perched as it is above the Great Rift. Besides, the long-drop is conveniently downwind; it serves well enough if it is dug out regularly, although the thought of this chore makes him sigh. Like much else these days, such jobs get no easier.

Shunting across the yard, his boots are soon so caked with mud that they are hard to lift. This gives him the oddest sense of moving forwards only to slide back to where he started. For a moment he stands still to check progress and, glancing back to the kitchen door, suddenly sees the funny side.

Ha! Moving forward to slide back? Sounds like some joke government slogan. Well, isn’t that how life is now: everyone striving, but then ending up worse off than before? He must tell Rahab over their breakfast cuppa. Even she will see the humour of it. At least he thinks she might. Yes. Moving forward to slide back. What a joke.

He stops at the cattle pen to scrape the excess mud from his boots. At this rate he might never reach the privy in his lifetime. Two Ayrshire cows and three Jerseys push their faces at him over the fence. Five lots of breath make white plumes in the mist. Winston briefly pats each dewy nose in order of seniority: Lois, Lola, May, Primrose, Mumbi. All present. All correct. And yet?

He turns and looks around the farmyard, scanning the acanthus hedge where the fog hangs in shrouds. But it is not the fog that disturbs him; it is something else. It is silence. Not even a dove or starling calling. After the night’s thundering rain so much quietness is uncanny. He thinks of Rahab then, and wonders if she is awake yet. She sleeps so much these days; not even last night’s din disturbed her. Sometimes she seems to slip into another world, as if she is submerged in an old-age, silent fog all her own. He wonders if the endless rain is to blame (water on the brain?). All he can do is hope that she will come back to herself.

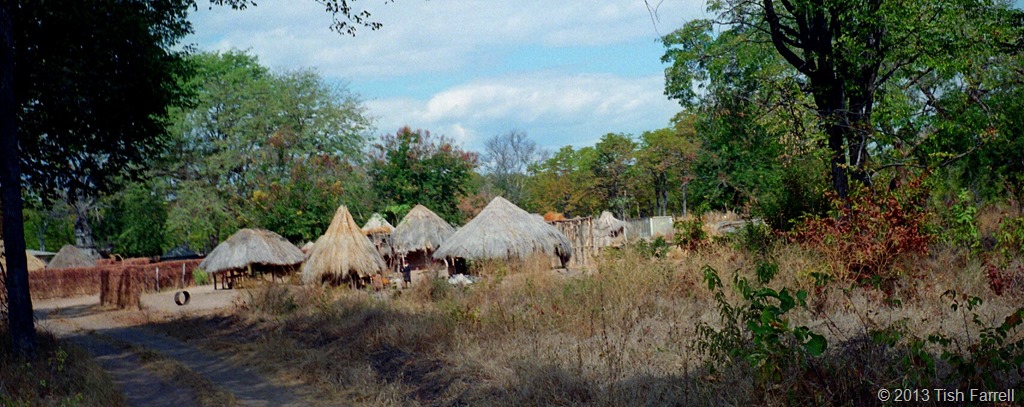

He presses on slowly across the yard, telling himself that he is not the only one to be worried by weather. Two days ago, during a lull in the rain, he and Rahab walked to Ingigi’s general store. They needed tea and maize meal. Along the lane the lantana bushes steamed under a misty sun, and people stopped to commiserate over the general quagmire. Not everyone was complaining though. Outside their neighbour’s Faith Muthoni’s place little Kui and another child were playing shop. They were having a fine time shaping rounds of mud and mango leaves, and setting them out on a banana leaf.

‘Mud pies,’ Kui cried when she saw them. ‘I will give you a good price.’ Then she dissolved into shy giggles when Rahab sparked into life and ordered ten. Winston at once repeated the order, trying to join in the children’s fun. The only problem was he could not be sure if Rahab was joking.

Further on at the market crossroads they found a big crowd trying to shunt Joybringer out of the mudslide that had spilled down the plum orchard above the bus stop. While the windows sparkled with old Christmas tinsel and Mickey Mouse grinned like a mad thing, tempers began to fray. City-bound travellers were suddenly sprayed in mud from a spinning back wheel, and this was the moment that Sergeant Njau turned up and tried charge the bus driver for causing a public nuisance. It was very poor timing on the sergeant’s part. Also Winston was astonished to learn there was such a crime. But Sergeant Njau had pressed his luck too far this time. The passengers, furious that any fine would be added to their fares, turned on him. The officer, faced with a mob of such unexpected ferocity, muttered something about ‘mitigating circumstances’, and quickly retreated to the Police Post.

Meanwhile Jimmy Mwangi, the local bar owner, caught Winston’s eye.

‘It’s like the Plagues of Egypt,’ he said, nodding at Sergeant Njau’s departing back. ‘If we’re not scourged by flood or drought or bugs eating our crops, it is swarms of bloodsuckers like him. Making money from other people’s misery. I ask you.’ But before Winston could think of a suitably non-committal reply, since he had learned from past experience not to voice opinions about officials in public, Samwel the butcher chipped in, ‘End of the world, that’s what this El Niño means. God is reminding us to repent, sending us these mudslides and floods. The Millennium will soon be upon us.’

By then Winston wished that he and Rahab had stayed at home, away from such alarmist forecasts. Even when they reached Quality General Store, Mrs. Kuria wailed that there had been no maize meal delivered and surely God was sending an absence of ugali to punish them for their wicked ways.

Winston could summon no suitable response to this either. Now, though, he thinks the doom-mongers may have a point, but only so far. God, he is sure, is not the culprit. Recently he has been reading the newspapers more carefully. He has learned, for instance, that the felling of the highland forests is changing the Rift Valley’s climate, lowering the water table, and loosening the light tropical soils so that they wash away with every rainstorm. On top of this, everyone knows that officials have been plundering the valuable hardwoods for years, and then clearing the rest for charcoal burning and bhang farming. And so, with the sacred soil thus exposed, El Niño strips the land as a slaughterman flays a carcass.

He knows where that soil ends up too. He discovered this quite by chance, three weeks ago when he called in at Jimmy Mwangi’s for a glass of home brew, something he did not usually do. As he stepped into the bar, there on the T.V. was a scene that stopped him in his tracks. An aeroplane was flying over the Tana Delta, and filming the vast red slick as it spread into the Indian Ocean. It did not take him long to realize that this was the outpouring of their very own river that rose in the High Rift hills; their own good earth flowing into the sea. The image of a severed artery sprang to mind. He began to feel faint. And that is when he knew. The homeland he had fought for in his youth was simply bleeding to death – kwisho and bye-bye. He turned on his heel and went home without ordering the drink.

Even now, recalling that scene gives him a stabbing feeling in his guts. He hurries onwards. When he reaches the drier ground of the hillside path he strides out, sidestepping the chickens coming the other way. (How the devil have they got out?) But there’s no time to think about that now. He throws back the wicket gate at the end of the path, takes the long-drop key from his trouser pocket, and steps into the field. But as lifts his hand to the place where the door should be, he finds there is no lock to open. No door either. Winston’s hand hangs in space. The latrine is gone. The ground it stood on too. Nothing left but a bloody mud slick.

It takes another second to sink in. Ngai, help him. Now he knows what the jigger meant. His life’s work is gone – the plots of coffee, tea, maize, the terraced banks of cattle grass – all swept away by a massive landslide from the hills above. Only the red subsoil remains. And something else. A big rusty egg lying in the dirt where the latrine should be.

Winston drops his trousers just in time. Dear Lord. Then finishing fast, he runs to warn Rahab. He knows what that giant egg can do. Forty-four years it must have been lying there on his farm. Forty-four years waiting to blow.

‘Rahab. Woman. Move!’

Available in Kindle at:

YOU DON’T NEED A KINDLE READER TO READ OR DOWNLOAD E-BOOKS.

GET A FREE KINDLE READER APP FROM AMAZON FOR ALL OF YOUR DEVICES HERE

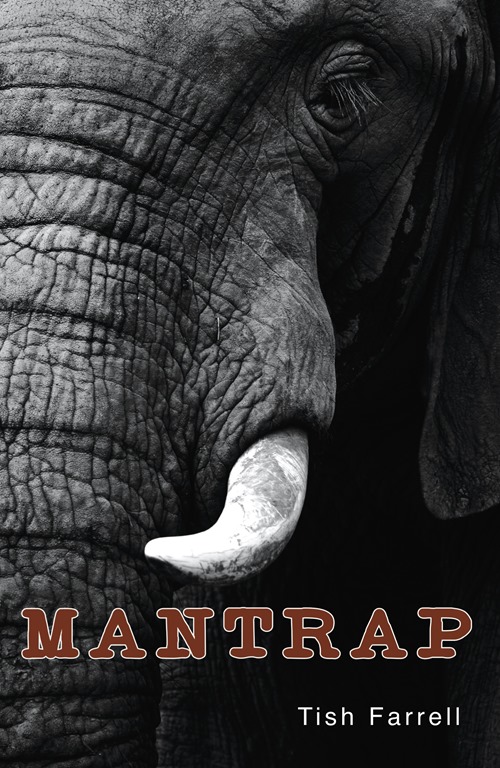

Secrets, conspiracies, tragedy, dark comedy – a fast-paced novella of interwoven tales set somewhere in East Africa

Things are going from bad to worse in Ingigi village. No one knows why five-year old Kui has gone missing. Nor does Sergeant Njau want to find out. He has his own problems, pressing matters that are far from legal. Then there is the endless rain. Will it never stop? Some Ingigi folk think it means the end of the world. Old man, Winston Kiarie, has other ideas. He senses some man-made disaster, and when it happens, it is worse than his worst imaginings. The fierce storms are causing landslides and throwing up British bombs, unexploded for forty years. Their discovery is giving the Assistant Chief ideas: how to make himself very rich. And then there’s young Joseph Maina and the primary school drop-outs thinking they have found treasure, and about to do something very foolish. Meanwhile, is anyone looking for Kui?

Available also on ePub Bud for Nook, iPod/iPhone etc HERE

© 2014 Tish Farrell