When we lived in Kenya we made three trips to the Maasai Mara, staying not at one of the luxury hotels inside the national park reserve, but at the small Mara River Camp. The camp’s landlords were the Maasai themselves, the Koiyaki Lemek Wildlife Trust, whose clan elders jointly owned three hundred square miles of plains grazing – albeit a tiny pocket of the Maasai people’s original rangeland i.e. the entire run of East Africa’s Great Rift Valley. Such jointly owned remnant land holdings are known as group ranches, though they not ranches as Europeans understand the term. Here clan members and their families live, tending their herds while also claiming daily game viewing revenue from the foreign visitors staying at the camp.

And in case anyone thinks staying outside the national park might be second best, it wasn’t. In fact there was so much wildlife to see everywhere, there was no need to go into the park proper. Die hard conservationists like to contend that wildlife and humans don’t mix, that humans have a detrimental effect on habitat. This attitude has caused, and will continue to cause extreme hardship to the world’s remaining traditional communities, people who actually know very well how to care for their own natural resources.

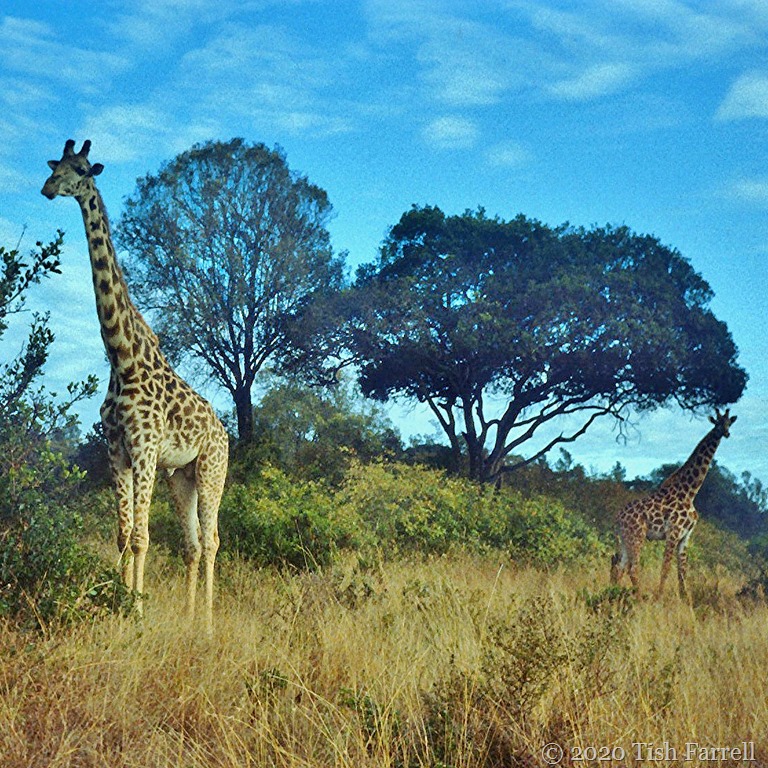

But back to our first game drive beneath the Oloololo Escarpment.

We set out from camp at 3.30 p.m. in a re-purposed Land Rover: six seats in the back, one per window and three viewing hatches cut in the roof. Daniel Mahinda, our driver-guide, was keen to please us. When he asked what interested us most Graham said ‘grasses’. A surprising answer in ‘big game’ territory. He had recently finished his doctoral thesis on smut disease in Napier grass, an important local fodder crop, but I suspected he was being a touch facetious. I had stopped him from taking a nap, saying he could not sleep through Africa. And he had grudgingly agreed. But, looking back, I should have left him in our riverbank tent – to be serenaded by grunting hippos. The crop protection project he was running in Nairobi was often very stressful, and for all kinds of reasons that could never be foreseen. Probably the last thing he needed was to be bumped around in the back of a Land Rover.

Daniel (on a later December trip) with our niece, Sarah and distant elephants

*

Anyway, Daniel took Graham at his word. Grasses it would be. This is what I wrote back then:

‘As we drive up the rocky valley out of camp there are several stops while Daniel picks us some red oat grass (characteristic of the Mara plains), pyramid grass, Maasai love grass and Bamboo grass. Then we stop to taste the leaves of the muthiga tree (the Kenya greenheart) which are very bitter, and Daniel says the tree’s twigs make good toothbrushes and the bark has medicinal properties – good for sore throats and toothache.

We look at the white tissue paper flowers that hug the ground and the tall sunbird plants (Leonotis leonotis) and the invasive thorn apple (Datura stromonium) and then Daniel picks us a pink flowering spike and says it is called devil’s whip. We also look at the clouds of white butterflies that are clustering round the thorn tree blossom. Then we forget about plants for a while and consider the sooty chat (a small bird that is a Mara speciality) and watch a huge breeding herd of impala. Then we drive along the meanders of the Mara River looking at baboons.

Daniel says there are about fifty in the troop with three alpha-males, and adds that they’re not averse to tackling a Thomson’s gazelle. We see those too. Then there is a grove of muthiga trees with every trunk bearing a series of scars (old and new) from where, over the years, small pieces of bark have been removed to make dawa (medicine). The Maasai are usually far from clinics, and so rely greatly on herbal remedies both for themselves and their cattle.

Soon after this we see elephants – first two males, one who shakes his big head aggressively as we draw near. We pause briefly for photos before driving across the marsh to see a family group whose matriarchs and young don’t mind us watching them for a while.

Among the muthiga trees

Among the muthiga trees

*

By now it is late afternoon and Daniel has been doing a lot of talking in Swahili on his truck radio. He sets off with purpose across the open grassland. After a while we see two stationary safari trucks on the horizon. We bump over tussocky ground towards them and pull up beside a swampy bank, and there they are – simba. Cubs and lionesses idling in the grass. The drivers confer over their radios, and once agreed that no hunting is in progress we move in closer. At first Daniel pushes along a grassy peninsula away from the pride and we wonder why, for all we can see is grass. But he knows where he’s going. And when a young adult lion raises his big head, I am stunned. Anyone on foot would scan this meadow-like terrain and not have one inkling that the lions were there. When the head goes down, he is gone: lost from view in twelve inches of grass.

Daniel tells us there are six cubs, survivors from a litter of ten, the other four having died because the hunting has been poor; but, he adds, the wildebeest migration is about to start and these six now look likely to survive. We watch eleven big and small lions till the light fades to grainy grey and then leave them in peace. On the track not far from the camp we see a pair of bat-eared foxes – ‘Very rare,’ says Daniel. They eye us anxiously before trotting away into the grass.

copyright 2020 Tish Farrell

Lens-Artists: Distance This week Tina sets the challenge. One of the safari guide’s key skills is knowing when it’s best to keep a distance and especially when it comes to elephants and lone buffalo.