*

I rather miss having the Iron Bridge on our doorstep. It’s now a good hour’s drive across the county from our house in Bishop’s Castle. We used to like wandering along the Wharfage beyond the bridge, gazing up at the hanging woodland along Benthall Edge. It’s a great place for promenading, or at least it is when the River Severn is safely in its bed.

River Severn on the rise

*

The Iron Bridge, though, has withstood the most tremendous deluges, including the great flood of 1795 that took out most of the old stone bridges from Shrewsbury to Worcester. It was a show of resilience that proved to anyone who had doubted the capacities of large cast iron structures, that its builder, Abraham Darby III, had been right all along: cast iron was the material of choice for the industrial age.

Nor did its adoption take long. Soon it would be used to build the frames of factories; seen as a boon for the owners of textile mills whose combustible raw materials made them prone to ruinous conflagration. The several-storeyed iron-framed buildings that ensued were forerunners for the skyscrapers of the modern age.

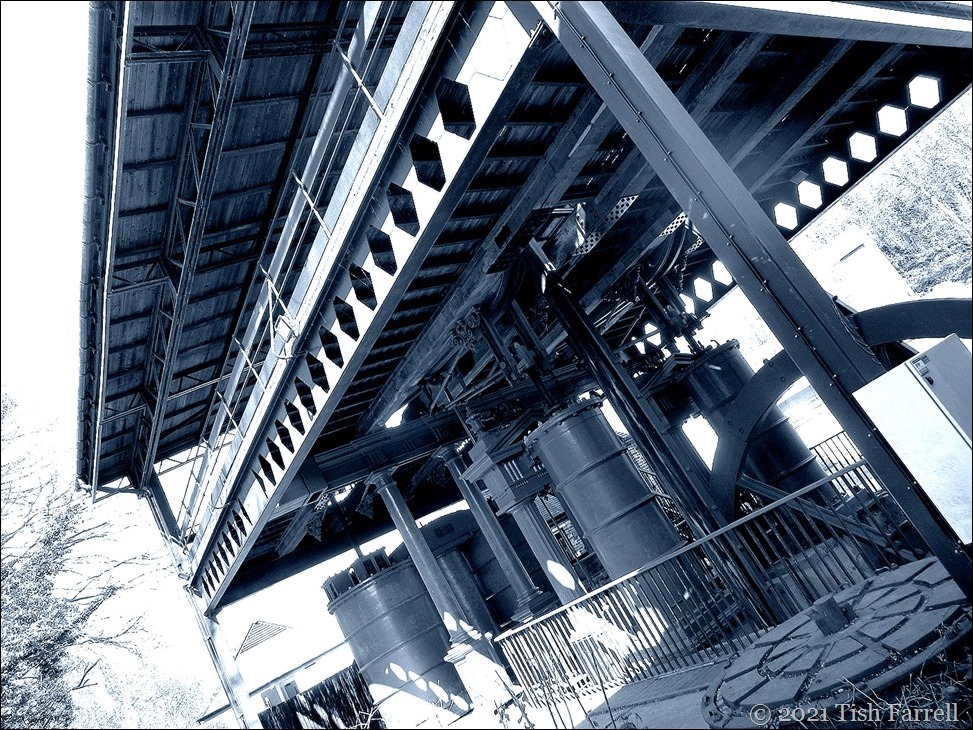

On closer inspection, though, Abraham Darby’s ‘world wonder’ innovation came with more than a hint of sticking to the tried and trusted. After all, the man was an ironmaster, from a dynasty of ironmasters, and thus a pragmatist, and while the use of cast iron for so big a project was breaking new ground, the hundred foot span was achieved by the jointing of over 1,700 castings, some weighing over 5 tons, and using centuries’ old woodworking techniques of dovetail, mortise and tenon joints.

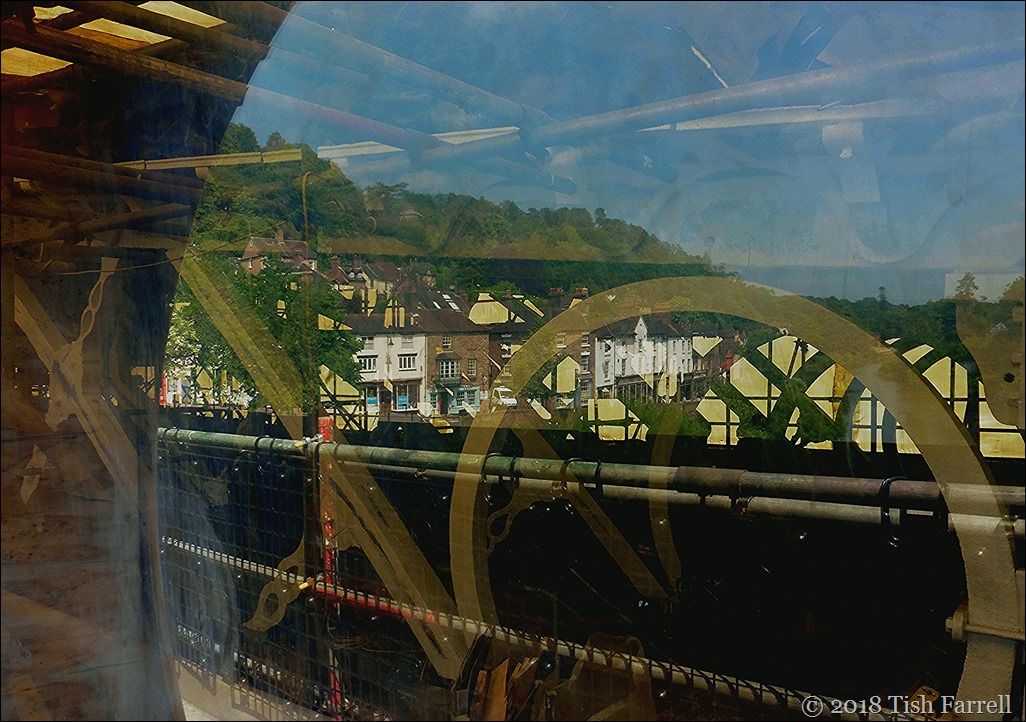

Besides, there was something else he was wanting to prove: that a bridge with a single arch could be made to span a waterway, busy with large sailing barges. To achieve this meant another significant breakthrough: the Severn trows could pass beneath without the nuisance of lowering their masts. It was all good for publicity.

‘The Cast Iron Bridge near Coalbrookdale’ by William Williams 1780

*

The bridge and the foundries, furnaces and forges of Coalbrookdale became the tourist venue of the age. Engineers, ironmasters, industrial spies and scores of artists flocked to wonder at what many likened to a vision of hell. The William Williams image above was painted a year before the official opening of the bridge to the general public. You can see three trows moored along the right hand river bank.

*

And of course, as a World Heritage site, the Iron Bridge is still a huge tourist attraction, seen here spanning a quiet and sluggish summer river.