The light changes every second across the lake. From dawn till dusk there is always something to watch at Elmenteita in Kenya’s Great Rift. There are over 400 species of birds to spot for one thing – among them the endangered white pelican that breeds there. The main stars, though, are the surely the huge flocks of flamingos, both lesser and greater varieties, that turn swathes of the lake to rose-petal pink. Even a passing glimpse from the nearby Rift highway is enough to catch the breath. A pink lake – how can that be?

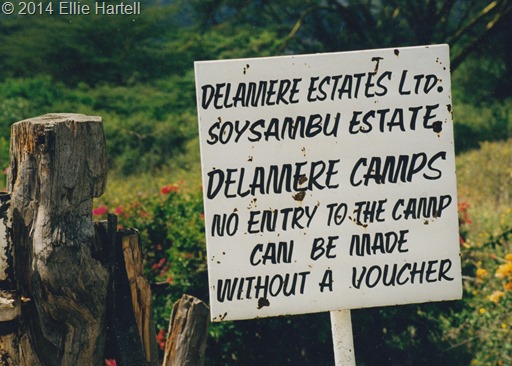

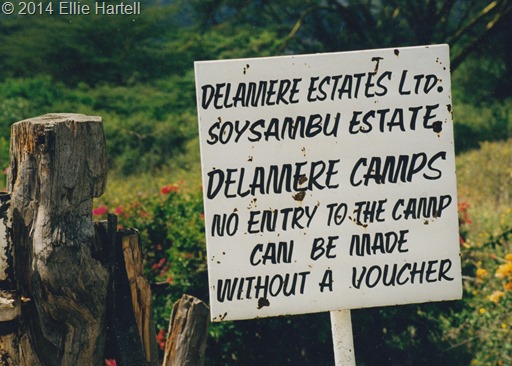

We came here often while we lived in Nairobi, staying at Delamere tented camp on the lake shore – a quirky, step-back-in-time establishment within its own nature reserve. The camp, itself was wholly unobtrusive -16 large tents, each sheltered by a thatched canopy and set out beneath fever trees that, here and there, hosted a sturdy canvas hammock.

The tents were functional – two wood-framed beds, simple cupboards, rattan chairs all locally made. They came, too, with a plain little bathroom attached out back – running water, flush loo and shower – all facilities that would still be an unobtain-able luxury to millions of Kenyans. Inevitably, knowing this added to the discomforting ‘them and us’ awareness that accompanied us pretty much everywhere.

For us wazungu, then, Delamere Camp was an idyllic spot. I once spent a week here by myself while G was at a conference. There were no other guests for most of that time, external and internal tourism having been hit both by El Nino rains that had caused weeks of havoc, and by widely reported bouts of pre-election violence. Manager, Godfrey Mwirigi, treated me as if I were his personal house guest.

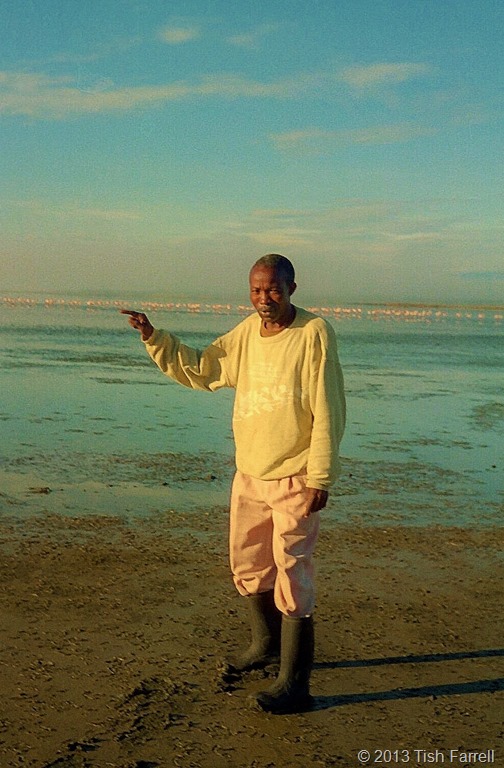

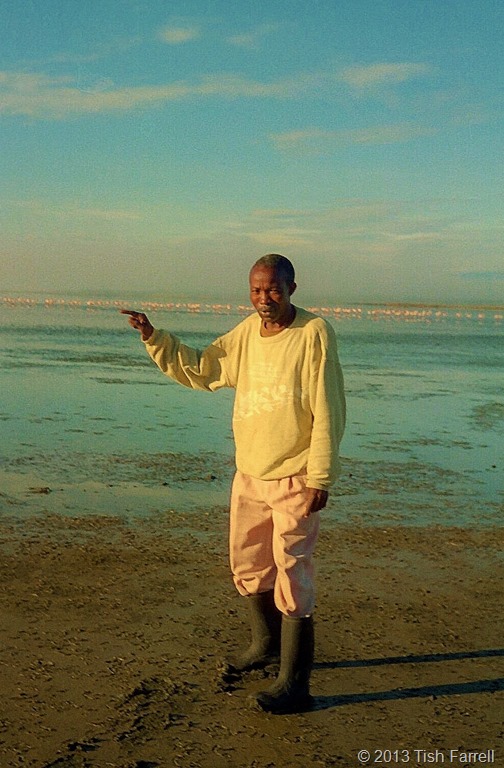

I thus spent my days and nights being driven around Soysambu nature reserve in a safari truck with zoologist, Michael Kahiga as my expert guide, or taken on early morning bird walks through the bush, or on late afternoon hikes up through the sage-scented leleshwa brush to Sogonoi cliff-top to watch the sun set over the lake with a glass of wine in my hand. This, the daily late afternoon pilgrimage to the sun-downer cliff, was a pleasing piece of hospitality thought up by Paul Kabochi, the camp’s ethno-botanist. I have written about him in an earlier post, but here he is again on the lake shore at dawn.

On this solitary sojourn I was sorry to find that he was away setting up another camp. He is a man whose great fund of knowledge is sadly missed, and I would have been glad to have had another chance to speak with him. Instead, I talked to Godfrey about tourism. He kindly ate his meals with me so that I did not have to sit in the dining room alone.

Between times, hot water bottles and extra blankets appeared like magic in my bed, or indeed in the truck for the evening game drives. (Nights in the Rift can feel frosty). And all the time I watched and watched until my brain ached with sensory overload.

The camp overlooked the lake and the remnant volcanic cone that has long been known by the Maasai as the Elngiragata Olmorani, the Sleeping Warrior. During colonial times it acquired a further name – Lord Delamere’s Nose, this apparently in tribute to the impressive dynastic proboscis of the third baron Delamere who, in the early 1900s, and as one of the first pioneer colonists, acquired 19 hectares (46,000 acres) of shore-land around the the east, north and west of the lake.

His brother-in-law, Galbraith Cole, son of the Earl of Enniskillen, farmed the southerly shores at Kekopey. He was a man who was later exiled from British East Africa because he shot dead one of his labourers for stealing a favourite sheep. He later sneaked back to Kekopey disguised as a Somali, and his mother, Countess of Enniskillen successfully pleaded his cause. At the age of 48, and looking out over the lake, he shot himself, unable to bear the constant pain of his rheumatoid arthritis.

The descendants of these early settlers still live and retain most of their lands (including estates at nearby Lake Naivasha). In fact the only way to gain access to Elmenteita is to book into one of the exclusive safari lodges that now stand on the land that belongs to these old colonial families. This sense of British aristocratic exclusivity inevitably strikes a sour note. Doubtless these landowners will say they are custodians and that, without their dutiful care, the place would be wrecked by ramshackle trading operations and squatters, and the wildlife decimated.

Even in my home town in Shropshire we are still ruled by such feudal argument. ‘Keep Out’ signs exclude the people of Much Wenlock from the ancient Priory parkland that is now owned by one family. In Great Britain we take for granted (or are even unaware of) the power of the self-appointed, self-aggrandizing elite who own most of our countries’ lands. I imagine, though, that many people would be surprised to know that super-squiredom is also alive and well in East Africa.

Before the British annexed East Africa in the 1890s, and all the (deemed) unoccupied territory became the property of the British Crown, and the locals obliged to stay forever on the land where the British happened to find them, land usage and territorial ownership was a much more fluid affair. For instance, up in the Rift highlands, and going back hundreds of years, the Kikuyu farmers had negotiated the legal acquisition of new land with the indigenous Okiek hunters, whom the Kikuyu judged to be the land’s original owners. Over the centuries this process of colonisation caused an occupational creep: as land became exhausted or overcrowded, so clan scions left their fathers’ homesteads and sought out fresh territories for their own families to cultivate. It is a similar story over much of the continent as the Bantu agriculturalists sought fresh ground.

As the boundaries of allotted farm and pastureland nudged further into the Rift, so there was competition and conflict with the pastoral Maasai. The herders anyway believed themselves masters of the Rift, shifting up and down it as need for fresh grazing and water dictated. The farming communities with whom they traded and inter-married also at times presented an alluring target. This was inspired by the cattle herders’ belief that Enkai, the creator, had bequeathed all the cattle on earth to the Maasai. For young warriors intent on proving their courage and amassing cattle to augment family honour, armed cattle raids on their farming neighbours were a matter of necessity.

It is interesting, then, that colonial aristocrats such as Delamere, who established large stock ranches in the Rift, were inordinately admiring of the Maasai, seeing them as nature’s aristocrats. It is also tempting to put this down to a congruence of world vision: recognition of a mutual case of droit du seigneur? In fact in those early days, Delamere was the only white man for whom the Maasai would deign to work, although this did not stop them from making off with large numbers of his sheep and cattle.

That the Rift was once Maasai territory is indicated by the many place names – Naivasha, Nakuru included – that are European renderings of Maa originals. Elmenteita derives from ol muteita, meaning “place of dust” and, from time to time, this shallow soda lake does turn to dust. At the best of times it is only around 1 metre deep. It shrinks and expands depending on the rains. But when not blowing away to dust, it extends over some 19-22 square kilometres.

The alkaline waters are rich in the crustacea and larvae that the greater flamingos feed on, and in the blue-green algae that the lesser flamingos syphon up through the top of their bills. The former have white plumage with a pink wash; the latter are more the colour of strawberry ice cream. Both honk, and grunt and mutter in a continuously shifting mass. All night you can hear them as you lie awake in your tent.

A view to dine for: Losogonoi Escarpment and the lake shore

*

But it is not only the bird life that make this place so special. The traditional ‘big five’ may be lacking in this part of the Rift, but it is still home to Rothschild giraffe, eland, buffalo, zebra, ostrich, impala, gazelle and a host of smaller game – aardvark, zorilla, porcupine, African wildcat. Since our time in Kenya much has changed at Soysambu. In 2007 the private Delamere Estate began operating as a not-for-profit conservation organi-zation called Soysambu Conservancy.

Delamere Camp has long gone. In its place is a new enterprise, the very expensive Serena Elmenteita Luxury Camp, a sort of out-of-Africa manifestation with bells on, the kind of set-up that intrudes a different kind of exclusivity on this piece of Kenya. But then of course there’s always the usual argument: that the provision of luxury on this scale does at least provide many, many jobs for Kenyans. Across the lake, however, something of the original Delamere Camp ethos has been re-created at the Sleeping Warrior Eco Lodge and Tented Camp – all within the Soysambu Conservancy.

In fact things have not been going well with the Delamere family. The sheer mention of the name has been enough to evoke great fury among many Kenyans. In 2005 and again in 2006, Thomas Cholmondeley, sole heir of the 5th Baron and Soysambu’s manager, admitted to shooting dead an African. The first case involved a plain clothes officer working for the Kenya Wildlife Service, apparently on the Soysambu farm to investigate a poaching incident. Cholmondeley says he thought the man was robbing his staff. Action against him was dropped.

In the second case, he caught a group of poachers with a dead impala, and said he was shooting at their dog when he fatally wounded one of the men. Later he claimed it was his friend, Carl Tundo, who had shot the poacher, and that he was covering for him. The whole sorry story was featured in the BBC Storyville film Last White Man Standing. Later the charge of murder was changed to manslaughter, and in any event Cholmondeley spent 3 years in Kamiti Maximum Security Prison, Kenya’s toughest jail. To many, though, it was thought to be far too lenient a sentence. The high profile media coverage also reminded millions of landless Kenyans that certain individuals had in their sole possession unimaginably vast estates. The old skeletons of racism and colonial oppression came rattling out of the cupboard to fuel the general furore, as the poacher’s widow asked for justice.

And so what in the end are we left with – a beautiful place enmeshed in tales of human intrigue, slaughter and misadventure.

I know I was lucky to spend so much time there when I did, and to see it through the eyes of the Kenyan naturalists who were my guides. I hope that many of them still work there – for Serena or Soysambu. They taught me how to watch out in that landscape: to recognize tracks of genet cat and mongoose, to poke through the little piles of dik dik droppings that marked this tiny antelope’s territory, to identify a black-breasted apalis or shy tchagra, to listen for the calls of the red-fronted tinkerbird, to know that an infusion of bark from the muthiga or Kenya Greenheart tree is good for toothache and stomach upsets, and most especially not to fall into aardvark holes as I was walking through the thornscrub.

Finally then, a few glimpses of Soysambu’s beautiful creatures.

Photos from bottom up:

Superb starling comes to breakfast

Waterbuck females

Dik Dik (one of the smallest antelopes, slightly larger than a hare)

Saddlebill stork, impala in the background

Eland (the largest of Africa’s antelope) and ostrich

Burchell’s zebra

Rothschild giraffe

© 2014 Tish Farrell

A Word A Week Challenge for more stories

![colonyinmakingor00cranuoft_0023[1] colonyinmakingor00cranuoft_0023[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/colonyinmakingor00cranuoft_00231_thumb.jpg?w=695&h=1097)