Elmenteita December 1997

*

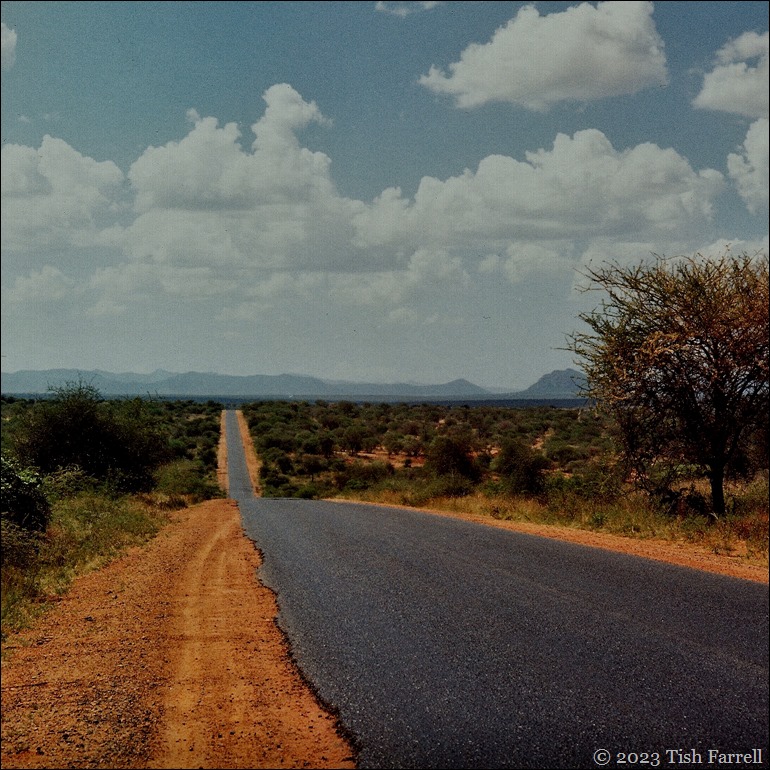

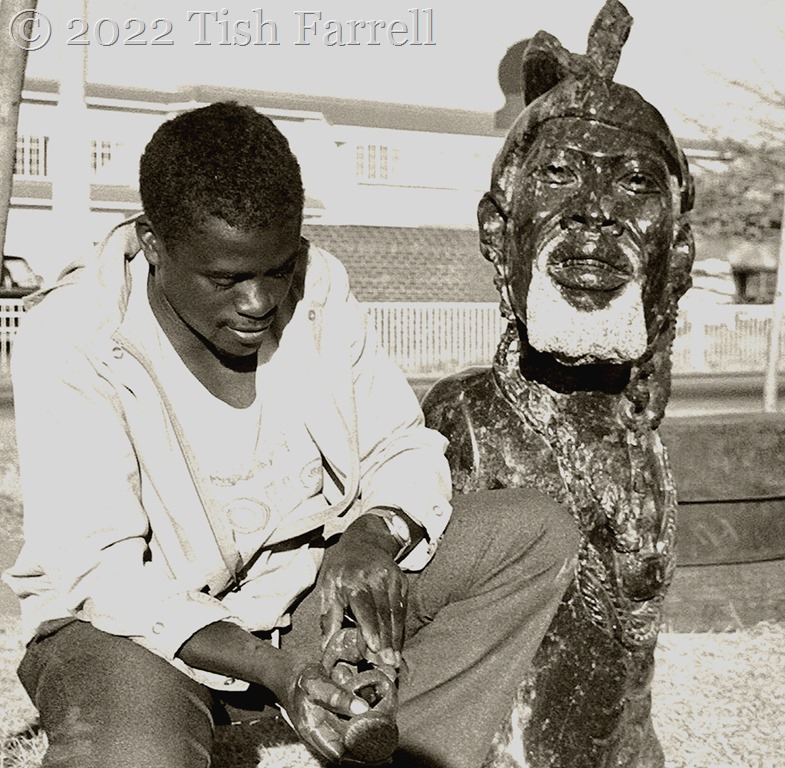

I’m having camera problems when I take this first photo, but in its way, it speaks of the times. It is early December 1997, our sixth year in Africa. There have been recent months of crazy weather with Kenya awash from El Niño floods and devastating downpours. When the rain rolls into the Great Rift, a lugubrious twilight descends, lowering in all senses. It feels cold too, and especially for a month that is usually hot; the equatorial summer in fact. Normally, too, October to December is the time of the short rains, the season for seed sowing. But instead of hopeful cultivation, there are reports of whole hillsides, entire farmsteads, being swept clean away.

The day I take this photo I’m with a Kenyan ecologist, Michael, a quietly spoken young man whose community belongs to the Central Province highlands. He has driven me out from Delamere Camp for a day’s excursion across the westerly reaches of Lake Elmenteita. We don’t have rain, but the light is poor and the landscape, at times, looks as dreary as an English November. We are heading south to an area of the lake known for its hot springs. But that story comes later.

*

And the reason this trip is happening is because my other half is some twenty miles further north up the Rift Valley, attending a three-day Crop Protection workshop at Lake Nakuru. And since he must drive past Elmenteita to get there, he’d had the kind thought to book me into the Soysambu Delamere Camp; once the workshop was done he would join me there for a couple more nights.

*

When I am dropped off on a Sunday afternoon, I find the camp sorely lacking in visitors. The bad weather, plus political tensions in the run up to the general election, including riots and a killing spree down at the coast back in August, are keeping tourists away. The only other guests are an English couple who have won the Kenya trip in a charity raffle. They are well-heeled, with connections in publishing and arms dealing, but know nothing of Kenya’s current political unrest. Having flown to the tropics out of a wintery England, they are put out to find they should have packed sweaters, raincoats and sturdier shoes.

View from Soysambu Delamere Camp: rain in the Rift and the Sleeping Warrior, a volcanic plug also known as Lord Delamere’s Nose.

*

*

I find myself in the care of Godfrey Mwirigi, the camp manager. He quietly ensures I do not eat alone, and joins me at every meal. Like the best party host he also presides over the clifftop sun-downer that happens each day at around 5.30. It is part of the camp ritual, guests are driven up through the sage scented leleshwa scrub to a high terrace above the lake. There they are met by the catering team presiding over a full bar and trays of tasty hot canapes. There is no stinting even though there are only three of us to please.

It is more than a touch surreal, both of itself and the Great Rift setting. Below us, the Sleeping Warrior sinks into blackness, while the lake slips through many shades of washed out pink and grey, and the day drops swiftly behind the Mau Escarpment. It is both beautiful and unsettling, one of those many times in Africa when I ask myself: where am I exactly?

*

Come nightfall and it’s time for a game drive around the reserve. The truck is roofed but open sided. We’re given blankets to fend off the chill. The air is dank, and the lakeside tracks perilous even with 4 wheel-drive. Now and then, disagreeable swarms of tiny hard-cased beetles fly in our faces. But then discomfort dissolves as the night theatre begins. While Michael drives, Dominic, another expert guide, rakes the trackside vegetation with the spotlight.

Eyes glow in the dark: eland, Africa’s largest antelope that can leap its own height over farm fences; buffalo, the most vengeful of all the big game; impala; waterbuck and, then among the fever trees and sheltered by underbrush, a shy steinbok. Out on the flood plains, spring hares, curious jumping rodents, bounce in every direction, creating their own mad light show before our spot-lamp. We come upon a genet cat and an African wildcat out on their night prowl. Then mongooses, a zorilla, porcupine parents with tiny porcupine twins in their new quill coats. And then Michael stops the truck and slowly reverses as Dominic scans along a grassy ridge.

The damp vegetation glistens, and in the halo of light a face looks back at us. A large leopard face. We’ve clearly disturbed him, lying in the grass, the intrusion prompting him to lift his head to check us out. For several moments he simply regards us. I’ve no idea if he can make us out behind the spotlight, but I have a sense of amber eyes looking deep inside my head: a non-consensual injection of leopardness; it does change me.

Finally, he blinks and lies back in the grass. The audience is over.

*

Masked weaver and nests

*

By day, the camp runs other activities. If you opt for the early morning bird walk, a tray of tea and biscuits is brought to your tent at 5.30. At six you set off with Dominic or Michael for an hour or two’s ramble around the camp perimeter. You can find yourself walking among impala and waterbuck while your guide runs off the names of all the birds that may be heard calling from trees and bushes.

If a bird reveals itself, you are told where to look for it, and the characteristics that define it. A morning walk thus can yield grey back fiscal shrikes, rattling cisticolas, Ruppell’s starlings (in brilliant violet and turquoise), the shy tchagra, a scarlet chested sunbird, and blue-naped mousebirds. You might also spot fish eagles or hear a golden oriel call or the song of an olive thrush or a robin chat whose repertoire makes me think of an English blackbird. There are 400 species to choose from here.

Later, after breakfast, there is usually a two-hour game drive, but on my third morning there is only me to be entertained. Godfrey says he has arranged for Michael to take me on a longer drive to the hot springs. We can take a picnic lunch.

*

As we set off along the estate’s perimeter road, Michael gives me the background on the Delamere Estate. He tells me there are 10,000 beef cattle on the Soysambu ranch, which adjoins the reserve. The name Soysambu is a Maasai word meaning mottled rock. He tells me, too, that the reserve was set up by Lord Delamere in 1990 as a means of protecting the lake shore from developers.

The estate had also included land on the East Rift escarpment behind the camp, but this had been sold off cheaply, and was now settled by some 15,000 people, each family farming 5 acre plots. Most of Delamere’s 200 employees have smallholdings there. But this has caused problems. Game that once lived in the former wilderness has now moved onto the ranch. And so his lordship’s cross-bred cattle also share their pasture with 600 eland, 300 buffalo and 200 zebra. It is literally a bone of contention among big landowners, that they are not allowed to cull the game for food.

Eland graze with Lord Delamere’s cattle

*

Michael also spots wildlife as he drives: a secretary bird, an augur buzzard, hoopoe, wheatear, Grant’s and Thomson’s gazelle, open-billed storks. There are zebra, giraffe and ostriches. The pink haze of flamingos across the water.

As we head out behind the lake, it looks as if we’ll be lucky with the weather. No rain, but very overcast. In a moment of brightness, as we rattle through thorn scrub, Michael spots a Kirk’s dikdik and I remember he has told me on an early morning walk how these tiny antelopes are fiercely territorial. They create middens where they go to defecate and urinate. While visiting, they scratch up the dung heap so their hooves can deposit their scent and reinforce the boundaries of their domain. It sounds a touch grubby for a creature so daintily pretty, but then that’s my problem.

Kirk’s dikdik – not much bigger than a hare

*

We drive past the Sleeping Warrior. The skeins of power lines running by take me by surprise. Electricity is often in short supply. That year there are daily three hour cuts in Nairobi, and most rural areas anyway have little or no access to the grid. Michael tells me the lines import electricity from Uganda.

*

Then suddenly, as if fallen in a time slip, we are among the Maasai. I have noticed a settlement, an ‘enkang with its mud domed dwellings. Now an elder in red kilt and blanket passes by us with a herd of goats. There is no obvious exchange. I see the dark bare legs, ebony hewn; not a pinch of flesh.

When we roll up at the hot springs on the southern lake edge, Maasai women are finishing up their washing in the hot water. Children, fully clad, are whooping and wallowing in the shallows. All soon retreat as if they have never been. When I look back I see the elder standing on a ridge with his goats, the red shuka against a stormy sky. I do not attempt to photograph any of this. This is not my place.

The Eastern Rift from the hot springs in Lake Elmenteita

*

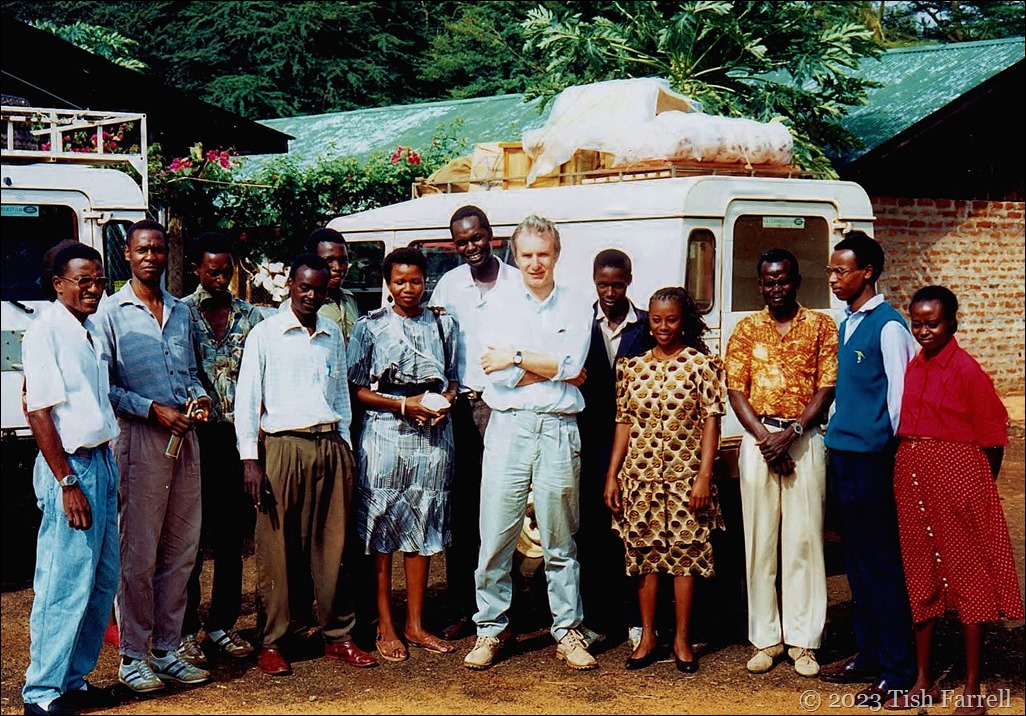

We sit under thorn trees and chat over the packed lunch. At some point the subject of Princess Diana’s death back in August crops up. I say am touched at how sorrowful Kenyans were, how they queued to sign the condolence book at the British High Commission, and how Graham’s colleagues at the research institute came to his office to offer their condolences. Michael tells me that his wife’s prized possession was a video of the royal wedding, although the only place they could play it was at the pub in their home village. You can guess the name of our daughter, he says.

I ask him where he worked before joined the team at Delamere Camp. He tells me that soon after he graduated with a degree in wildlife management, he was posted, as deputy wildlife district officer, to the remote quarter of mainland Lamu, in north-east Kenya. Somali cross-border bandit country, in other words. There, his job was to coordinate anti-elephant poaching operations, using local police or military, whoever he could rope in, sometimes using helicopters. He said that whenever he went into the bush, he never knew if he was coming back. The gangs were often 20-30 men strong, and with an official policy of shoot to kill, the stakes were high.

I am shocked as I listen to this account, told with such detachment: that an ecologist should be expected to do this kind of work. But Michael simply says he is finding Elmenteita much more to his liking, and especially as his wife and family are not far away. In the quiet understatement, I sense a man who has seen too much.

I feel uncomfortable too – some people don’t know they are born, do they, with all their sheltered good fortune. That would be me of course. Though I am learning. Kenya’s gracious people never stop teaching me. They teach me even now as I retrace my steps down the years.

*

copyright 2024 Tish Farrell