Caught in some dreamworld – it was often how it seemed that first year in Kenya. And nowhere verged more on the surreal than the Taita Hills Hilton*. A 5-star hotel in the bush. There it lies beside the road and rail to Taveta and the Tanzanian border. It is the territory of William Boyd’s First World War novel An Ice-Cream War, of a failing sisal plantation and border skirmishes between German Count Von Lettow Vorbeck’s Tanganyikan askaris and Kenyan British forces backed by coerced young Africans of the Carrier Corps.

And it is the place we often stayed when Graham was overseeing field work experiments up in the Taita Hills. After breakfast he would drive up the mountain to Mgange to speak with farmers and check on the Larger Grain Borer’s voracious appetite for stored maize…

![230_thumb[6] 230_thumb[6]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/230_thumb6_thumb.jpg?w=1026&h=677)

*

…and I would start my day, reading or writing beside the hotel pool. The pool was shaped like a teardrop, shaded on its southerly edge by flame trees. A thick hedge protected the garden from the adjacent wildlife reserve, the land there a failed sisal plantation run back to wilderness.

I’d look out there for hours, watching impala or zebra, sometimes giraffe nibbling the thorn trees, their slow passage through the brush; the soundscape a fizz of insects, swelling ever louder as the day warmed, the non-stop call of ring-necked doves, both strains somehow fusing into the heat haze that shimmered over the bush country. You can see how it might drive you mad. Meanwhile, inside the garden, a hosepipe hissed and swished, watering the lawn, where clouds of black butterflies with azure flashes came to sip.

*

The hotel was usually very quiet in the mornings. The staff went about their daily chores, tidying, sweeping, making ready for the next arrivals. I often saw them in the garden quietly picking hibiscus flowers to put in the rooms or to decorate the dining tables.

Garden tidying – a never ending job

*

The maintenance men

*

Around noon, fleets of safari vans, up from Mombasa, or down from Amboseli, would start arriving, their occupants spilling out, mostly young folk clothed in skimpy beach wear. They would be welcomed into the great hall with gentle decorum, glasses of chilled fruit juice set out on flower decked trays, but the tide of newcomers could never be quite contained – the rush to the bar, the scramble to join the lunch queue in the baronial dining room. Those tourists who did check in, usually only stayed one night and were off after breakfast. And so we became the centre of enthusiastic attention from the hotel staff. We stayed longer; five days on one occasion. ‘That’s almost a week,’ one waiter told us approvingly; we were doing them and the place proud.

![Taita Hilton - safari vans come and go_thumb[5] Taita Hilton - safari vans come and go_thumb[5]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/taita-hilton-safari-vans-come-and-go_thumb5_thumb.jpg?w=1026&h=658)

*

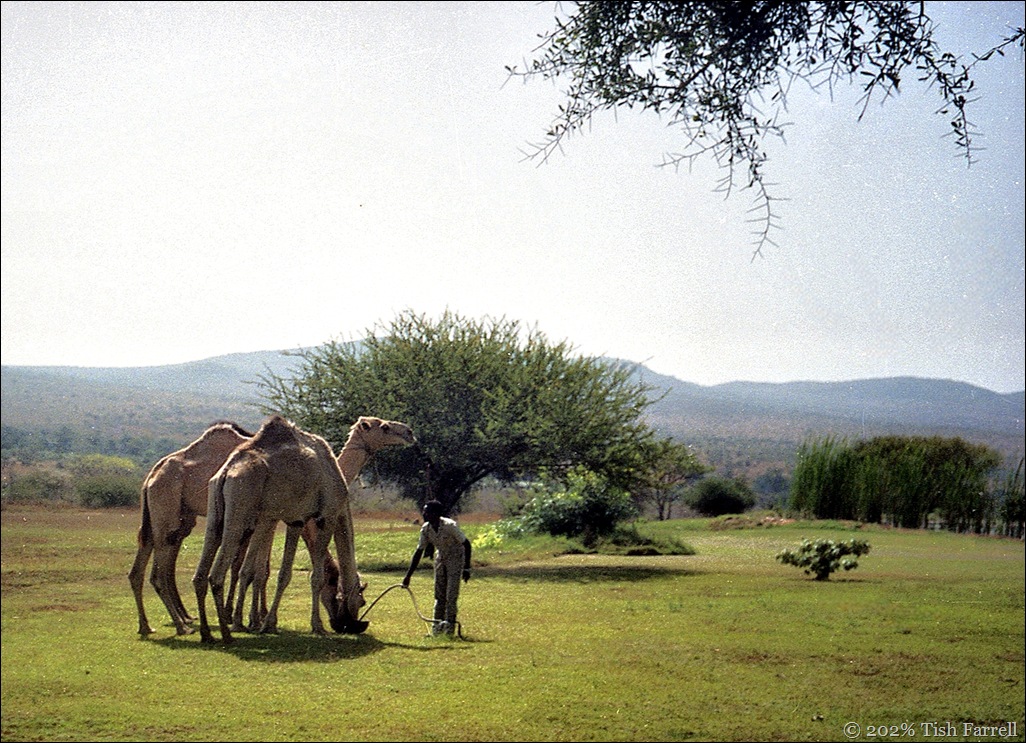

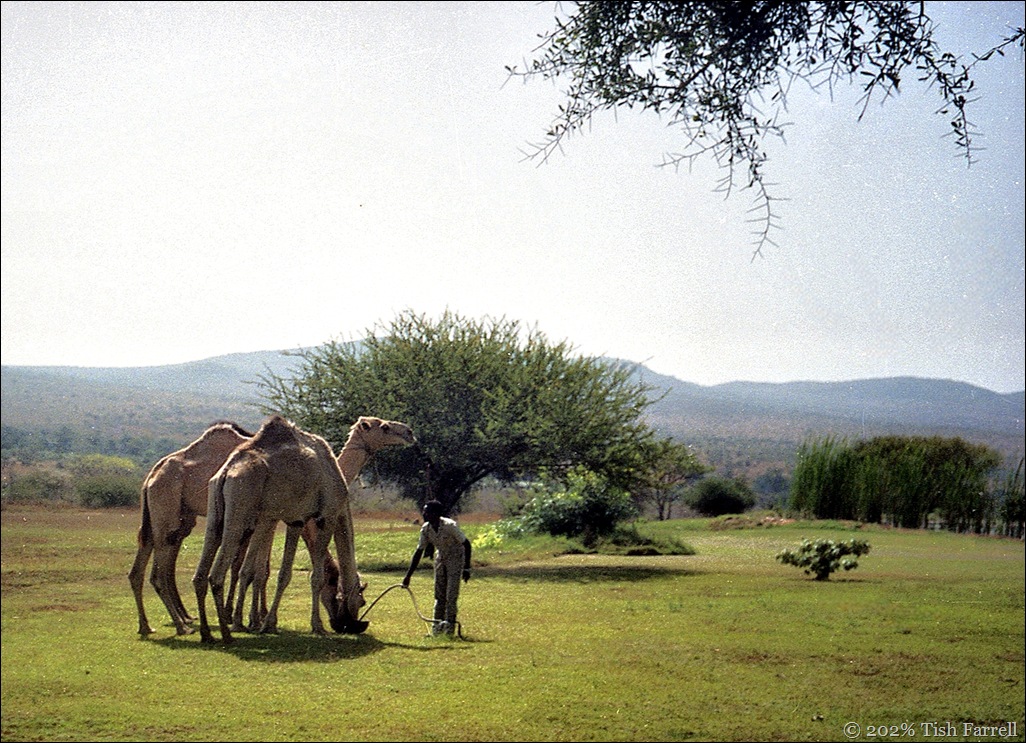

In the garden, somewhat oddly, were a trio of camels, kept for those moments when a tourist might have a burning ambition to ride one. They didn’t go far, just to the end of garden and along the edge of the reserve. Once on a family visit, our seven year old niece, Sarah, surprised us all by being very sure that she wanted a ride. Such savoir faire on the dromedary front. Here she is with Robert the camel fundi. Ah, how time passes. She’s now a chemical engineer working in fusion technology.

Taita Hills garden and the reserve beyond

*

In my wanderings about the place, I discovered I could climb up to the hotel roof. Sometimes, towards sundown, if Graham hadn’t returned from the mountain, I’d go up there and lean on the parapet, looking out for the Land Rover on the Taveta road. All around swifts and swallows swooped and swirled and, briefly, I’d think of the Shropshire home I’d left, and that soon these small birds would be leaving for their English summer.

And once when I was up there at twilight, the day fading fast, and no sign of headlights on the road, I saw shadow elephants crossing the railway line. At that moment Africa felt very very large. Unfathomable. Another dreaming interlude.

*now the Taita Hills Sarfari Resort & Spa

#SimplyRed Day 20

![Taita Hilton - header _thumb[5] Taita Hilton - header _thumb[5]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/taita-hilton-header-_thumb5_thumb.jpg?w=1282&h=565)

![230_thumb[6] 230_thumb[6]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/230_thumb6_thumb.jpg?w=1026&h=677)

![Taita Hilton - safari vans come and go_thumb[5] Taita Hilton - safari vans come and go_thumb[5]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/taita-hilton-safari-vans-come-and-go_thumb5_thumb.jpg?w=1026&h=658)

![Taita Hilton - header _thumb[5] Taita Hilton - header _thumb[5]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/taita-hilton-header-_thumb5_thumb.jpg?w=1282&h=565)