Believe me, the family gathering depicted in these two murals has more tales to tell than most. They could be the very depiction of Tolstoy’s famous opening to the tragic novel Anna Karenina: (and I paraphrase) all happy families look alike, but the unhappy ones are unhappy in their own inimitable way. I leave you to decide which sort we have here.

But before the stories, first a little about the murals’ setting. They face one another across the top of the grand staircase in the Palais Masséna in Nice. This imposing house was one of the last of its kind to be built on the Promenade des Anglais, looking

out on the sparkling blue Mediterranean. It was designed by Danish architect Hans-Georg Tersling (1857-1920), and finished in 1901. By then Nice had long been a thriving upper class resort, a trend begun in the 1730s when British aristocrats such as Lord and Lady Cavendish first began to gather at Nice and along Côte d’Azur for the winter season. Back then Nice was an ancient fishing town. The Scottish poet, Tobias Smollett describes it in 1764. He went there in hopes that the benign winter climate would help improve his consumption:

“This little town, hardly a mile in circumference, is said to contain twelve thousand inhabitants. The streets are narrow; the houses are built of stone, and the windows in general are fitted with paper instead of glass. This expedient would not answer in a country subject to rain and storms; but here, where there is very little of either, the paper lozenges answer tolerably well. The bourgeois, however, begin to have their houses sashed with glass. Between the town-wall and the sea, the fishermen haul up their boats upon the open beach.”

As time went on the Tsars of Russia and the Romanov family made the South of France their second home, which circumstance, in 1912, prompted Tsar Nicholas II to build the Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Nice to serve the Russian nobility. Even Queen Victoria came on holiday to Nice, staying in the magnificent Excelsior Régina Palace which looks down on the city and the sea from the hill of Cimiez. It was apparently built in response to her requirements for a place to stay that matched her status. And so the hotels and palaces grew up around the old town of Nice to provide for the royal, rich and famous.

![Le_Regina_à_Cimiez_6_Fi_09_0041[1] Le_Regina_à_Cimiez_6_Fi_09_0041[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/le_regina__cimiez_6_fi_09_00411_thumb.jpg?w=512&h=383)

Excelsior Regina Palace built 1895-7; Photo: Nice Archives copyright expired

*

![Angelo Garino Promenade des Anglais 1922[1] Angelo Garino Promenade des Anglais 1922[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/angelo-garino-promenade-des-anglais-19221_thumb.jpg?w=507&h=329) Detail from Promenade des Anglais 1922 by Angelo Garino (1860-1945)

Detail from Promenade des Anglais 1922 by Angelo Garino (1860-1945)

*

Some of these elite visitors and palace owners acquired their riches and nobility by rather questionable means, and this includes the erstwhile owners of the Palais Masséna. It was built for Victor Masséna, 3rd Prince d’Essling, 3rd Duc de Rivoli and the grandson of André Masséna, son of a Nice shopkeeper who acquired wealth and royalty while serving and plundering in Bonaparte’s army. More of him later.

The two family murals are dated 1902-3 and include members of the intermarried Masséna, Murat and Ney families. The reason for the elevated positions and princely titles is entirely due to Napoleon Bonaparte and his ambitions of military conquest. The founders of their ennobled dynasties were three ordinary men from ordinary backgrounds who joined the French army. All three proved to be brilliant and courageous soldiers who ascended rapidly through the ranks to become Marshals of Empire.

Joachim Murat, an innkeeper’s son, married Bonaparte’s youngest sister, Caroline, and for services rendered was made the King of Naples. He ruled between 1808 and 1815.

*

Michel Ney, a public notary and surveyor of mines, gave up being a civil servant and enlisted in the hussars. After great battle victories he became 1st Prince de la Moskowa, 1st Duc d’Elchingen.

*

As mentioned above, André Masséna earned the titles 1st Duc de Rivoli and 1st Prince d’Essling.

*

But status and wealth are not everything. Nor were they enjoyed for long. Masséna, long suffering from ill-health, died in retirement after being serially dismissed by Napoleon, first for excessive war looting, and then (after reinstatement) for military failures against the British in the Peninsular War. In his last days before his death in 1817, he supported the restoration of King Louis XVIII to the French throne. Doubtless a wise move for his descendants.

In 1815, after the capture and exile of Napoleon Bonaparte, both Murat and Ney were executed by firing squad for treason. Murat’s two sons went to North America in the 1820s; the elder stayed and became a citizen, but the younger, Napoléon-Lucien-Charles returned to France in 1848 when his title as Prince Murat was recognised by Napoleon III under the Second Empire.

*

And so we come back to the descendants of the three brave Marshals on the walls of the Palais Masséna. The more you look at these murals, the more curious they seem. They were painted by the then successful French artist François Flameng (1856–1923). He later went on to paint Great War battle scenes, and document new kinds of families, the close-knit comradeship of companies of men under siege.

![300px-A_Machine-Gun_Company_of_Chasseurs_Alpins_in_the_Barren_Winter_Landscape_of_the_Vosges._painting_by_Francois_Flamenge[1] 300px-A_Machine-Gun_Company_of_Chasseurs_Alpins_in_the_Barren_Winter_Landscape_of_the_Vosges._painting_by_Francois_Flamenge[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/300px-a_machine-gun_company_of_chasseurs_alpins_in_the_barren_winter_landscape_of_the_vosges-_pa1.jpg?w=521&h=411)

A Machine Gun Company of Chasseurs Alpins in the Barren Winter Landscape of the Vosges, François Flameng, photo Wikimedia Commons.

*

![DSCN4945[1] DSCN4945[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/dscn49451_thumb.jpg?w=529&h=480)

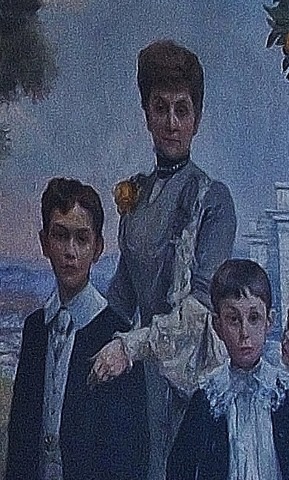

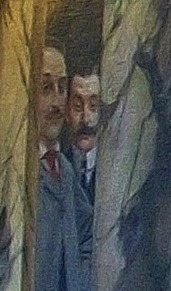

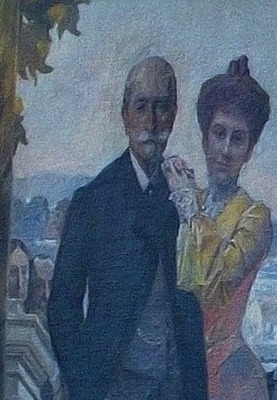

I suppose my first question is why would the mural people wish to have themselves depicted in this way? Certainly there is a sense of entitlement and much self-regarding, but at the same time it is also as if they are not quite self-aware. Flameng verges on caricature for most of his subjects. For surely there are suggestions of secrets, collusion, factions, conspiracy, loss of status within the gilded circle. There are shared misfortunes and private sorrows; anxiety and repression; no one smiles; the children look utterly constrained. And then there are simply too many people peering round pillars, or only half seen despite their prestigious titles.

The two men on the far left of the second painting look distinctly rascally, their almost-smiles, sardonic, malicious. They are related, brothers I think; the nearest to the viewer is Napoleon Ney, Prince de la Moskowa; behind him Claude Ney, Duc d’Elchingen. In 1903, the year the murals were completed, the Prince and Princesse de la Moskowa were divorced. La Princesse is the sad woman in the blue gown at the other end of the mural, only partially seen behind the column. Is Flameng intimating her loss of status in relation to the others? She is Eugénie, youngest daughter of Napoleon Bonaparte. She married the Prince in Rome at the Villa Bonaparte in 1898, and with all the Ney family in attendance. The couple had no children.

Here is Eugenie on her wedding day. The photograph is attributed to Count Guiseppe Primoli.

*

Further along the mural from the Ney brothers is Victor Masséna, Prince d’Essling, the builder of the palace. His eldest daughter, Anne, has a proprietorial hold on his shoulder. He will die in 1810 in a Paris nursing home after an operation, and she will marry the Duc d’Albufera. The two faded souls at Victor’s elbow are his long-dead parents, also named Anne and Victor.

The only calm and truly sympathetic face among the whole gathering is that of Rose Ney d’Elchingen. She leans over the balustrade accompanied by two macaws and an expensive tapestry. Beside her (with the pince nez) is the Princesse Joachim Murat, born Cecile Ney d’Elchingen, probably Rose’s sister. Her husband, Prince Joachim Murat, is across the stairs, lurking between a pillar and a large urn. Rose, herself, will marry the distinguished Italian politician Duca Guiseppe Lanza di Camastra, and he will die prematurely in 1927 at the age of 31. Before that though, a 1916 newspaper photo will show Rose La Duchesse in full nurse’s gear, apparently assisting the surgeon with the war wounded at Val-de-Grâce military hospital in Paris. She is well-known for her beauty and philanthropy.

Also in this mural detail is Prince Eugene Murat and the boy Charles Murat. The prince will die, aged 30, in 1906 when he overturns his car while driving to Karlsbad. The report says he lived in Paris and left three children. It does not mention that he was married to the notorious Violette Ney d’Elchingen, Princesse Eugene Murat, and Rose’s sister. We are about to meet her across the staircase. They could not be less alike, at least in their demeanour.

In fact you can hardly miss her, can you, Madame in the royal blue blouse. She seems to dominate the gathering on both sides of le grand escalier. The hand on hip gesture looks coarse, suggestive more of a nicoise fishwife than a princess. She is also the only one taking an active, indeed aggressive stance. She looks out at us visitors as if we were something unpleasant she has stepped in.

But what did the artist Flameng mean us to understand from this image? And what is going on with sad, submissive girl who leans against the redoubtable Violette? After all, this is not mother and daughter. The girl is Victoire Masséna, younger daughter of Victor. She is around 14 years old here. In 4 years she will be married to the Marquis de Montesquiou. She will have two sons and at 30 she will be dead. Perhaps she foresees her future. Perhaps when you know that Violette, besides being a mother of three, is also a predatory bisexual, you might think there is something more sinister here. But then maybe one should not jump to conclusions.

![tumblr_m74mcdKjfO1qjm0dlo1_500[1] tumblr_m74mcdKjfO1qjm0dlo1_500[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/tumblr_m74mcdkjfo1qjm0dlo1_5001_thumb.png?w=300&h=392)

Princess Eugene Murat c.1929; photo Berenice Abbott

*

In the decades of her widowhood, after the car-crash death of Eugene, Violette led a very gay life, and in all senses of the word. She was part of the Paris and Harlem Jazz Age scene. She entertained the likes of Stravinsky and Cocteau in her Paris home. She was a friend of the artist Augustus John who sketched her quite pleasingly while she introduced him to novel ways of taking hashish. In his autobiography he says:

“I had already tried smoking this celebrated drug without the slightest result. It was Princess Murat who converted me. She contributed several pots of the substance in the form of a compôte or jam. A teaspoonful was taken at intervals.”

She famously stormed out of a very famous Paris dinner party, held in 1922 for Europe’s artistic elite. The guests of honour included Diaghilev, Stravinsky, James Joyce, and Picasso. But it was the appearance of the reclusive Marcel Proust that evinced Princess Murat’s all too visible disfavour. At the time everyone who was anyone was trying to identify themselves and others in the characters of Proust’s À la Recherche du temps perdu. Violette, who was renowned for meanness had seemingly provided the model for an extremely miserly individual.

She was, in fact, exceedingly generous with the cocaine, or so we discover in Sebastian Faulks’ book The Fatal Englishman, which includes the biography of the English artist, Christopher Wood (1901-30). In it he describes Violette as “an enormous drug-addicted lesbian with a hunger for company.” She goes around with a bag of cocaine and lays out lines for Wood when he is struggling to complete a piece of work. Faulks tells, too, of Wood’s claim that she lost £5 or 6 million in the 1929 Stock Market crash. She ended her days, living in squalor, having overcome an earlier obsession with maintaining cleanliness, and died of barbiturate poisoning at the age of 58. A sad end to a damaged life.

And what was at the heart of this – sibling jealousy perhaps? Does that explain Flameng’s placing of the players in the murals – the beautiful Rose on one side of the stairs, blissfully unaware of her allure, and beloved even by the two family macaws? While opposite, the portly, coarse featured sister tries to outface her, and indeed the whole world that pays court to her much prettier sister. It’s a theory.

Finally, there is a more pleasing story, at least as far as the palace is concerned. Below on the left we see Victor Masséna’s heir, André, the future Prince d’Essling beside his mother, Princesse d’Essling. In 1919, with his father dead nearly ten years, he hands the Palais Masséna to the city of Nice on the understanding that it will be open to the public. Today it is the city’s local history and art museum.

And so what is there left to say about this self-aggrandizing family. With hindsight one could say that in real life, when these murals were painted, the Belle Époque was drawing to its close. Did Flameng already sense this? The world was changing. Soon there would no longer be the annual winter retreat to the Palais Masséna. Somehow, then, the murals do have a Proustian feel, perhaps a missing story thread from À la Recherche du temps perdu; the last moment of a perfect, and rarified age caught in two wall paintings, and now gawped at by the passing public.

And as for the three Marshals of France whose derring-do started all this social climbing, you may find them lying quite close to one another in the Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris. There they have long since made their residence – among the great and growing family of the dead.

Père Lachaise Cemetery, in Paris.Photo: Pierre-Yves Beaudouin / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0

*

Last but not least, I leave you with glimpses of former winter season glory chez Masséna.

© 2014 Tish Farrell

![Le_Regina_à_Cimiez_6_Fi_09_0041[1] Le_Regina_à_Cimiez_6_Fi_09_0041[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/le_regina__cimiez_6_fi_09_00411_thumb.jpg?w=512&h=383)

![Angelo Garino Promenade des Anglais 1922[1] Angelo Garino Promenade des Anglais 1922[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/angelo-garino-promenade-des-anglais-19221_thumb.jpg?w=507&h=329)

![300px-A_Machine-Gun_Company_of_Chasseurs_Alpins_in_the_Barren_Winter_Landscape_of_the_Vosges._painting_by_Francois_Flamenge[1] 300px-A_Machine-Gun_Company_of_Chasseurs_Alpins_in_the_Barren_Winter_Landscape_of_the_Vosges._painting_by_Francois_Flamenge[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/300px-a_machine-gun_company_of_chasseurs_alpins_in_the_barren_winter_landscape_of_the_vosges-_pa1.jpg?w=521&h=411)

![DSCN4945[1] DSCN4945[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/dscn49451_thumb.jpg?w=529&h=480)

![tumblr_m74mcdKjfO1qjm0dlo1_500[1] tumblr_m74mcdKjfO1qjm0dlo1_500[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/tumblr_m74mcdkjfo1qjm0dlo1_5001_thumb.png?w=300&h=392)