For those of you who read my recent post Valentine’s Day Runaway this is one of the things Team Farrell got up to next; it had a lot to do with smut. And no: it’s not what you think.

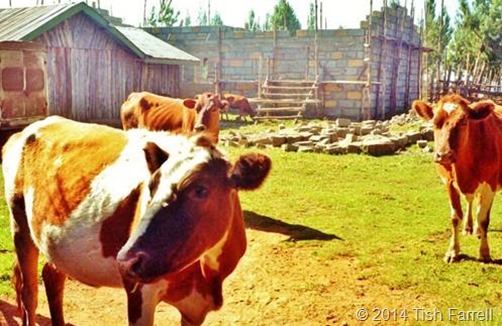

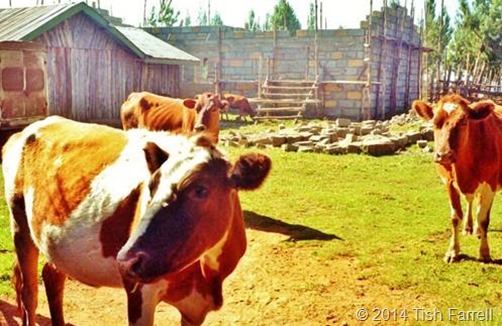

Smallholder farms on the Great Rift Escarpment, Kenya

*

For most of the 1990s we were based out in Kenya, where Team Leader Graham, food storage expert and all-round fix-it man, was one of several British scientists running a crop protection project alongside Kenyan scientists at the National Agricultural Research Laboratories (NARL). This work was funded by DFID, Britain’s Department for International Development, which in turn is of course funded by British taxpayers.

Most of Kenya’s farmers are women. Their efforts feed their families and feed the nation.

*

Many of the project’s programmes of work were done on farms, and involved helping farmers to devise their own research methods for controlling the numerous pests that attack their crops both before and after harvest. Since just about every Kenyan, from the President down, is some kind of farmer, or has a farm in the family, this was an important project, and just about everyone was interested in the outcomes. (Next time you are buying French beans or mange tout peas in the supermarket, look where they have come from. Much of this kind of produce is grown under contract on small farms like the ones below.)

A typical farmstead in the Kenya Highlands north of Nairobi. The volcanic soil is very fertile, but also susceptible to erosion.

*

Today Kenya is undergoing a massive hi-tech revolution through the proliferation of cell phone and computer technology, but it still relies on agriculture for survival. When you discover that only 15% of Kenya’s landmass has enough rain or is fertile enough for arable production you may begin to see the scale of the problem for a nation that is only now beginning to industrialize. There are of course the big multinational outfits that grow wheat, coffee, tea, flowers and pineapples, but most of the food that Kenyans eat is grown on thousands of tiny farms, many less than an acre in area.

Gathering Napier Grass from roadside plots to feed ‘zero-grazed’ dairy cows. Most farms are so small that cattle are kept in small paddocks and their food is brought to them: yet another daily chore, along with gathering cooking fuel and attending to children and fields.

Furthermore, most of Kenya’s farmers are women. Providing most of the the country’s food, they are in every sense the backbone of the nation. They stay in their rural homes, tending the crops and bringing up the children while husbands work away to earn extra cash to repair homes, buy fertilizer, educate their children and fund small business enterprises.

These men usually head to the cities where they work as security guards, clerks, hotel staff, house servants and drivers. Most take their annual leave at harvest and planting times so as to be back on their farms to help with the year’s most arduous tasks. So however you look at it, everyone in Kenya works very hard. Certainly in the nineties even most professional Kenyans believed that owning a plot of land to work at weekends was an essential insurance policy in a nation with no social services.

Most of the milk from smallholder’s cows is sold to provide cash to pay for children’s education and medical bills. While primary education has been free over the last few years, there are still expensive books and uniforms to buy, and secondary education is not free. On this farm the owner is also using any disposable income to bit-by-bit replace his timber farm house with a good stone house.

*

So back in 1998, as part and parcel of protecting Kenya’s agricultural production, Team Leader Graham invited Nosy Writer (me) to accompany him on a fact finding mission around the farms north of Nairobi. We were on a quest to plot the incidence of SMUT, a fungal disease that was affecting Napier Grass, an important fodder crop. Most smallholders kept a small number of dairy cows because the selling of milk provided a valuable supplement to their income, helping to pay for school fees and medical expenses.

Most farms are too small to include pasture and so the cows are ‘zero-grazed’, that is, kept in small paddocks and their fodder (mostly Napier Grass) brought to them. This grass, if well-tended, grows into huge perennial clumps that can be cut at intervals. It can also be usefully grown on vertical banks to consolidate field terraces, or wherever the farmer can find a space, often on roadside verges. However, once smut gets a hold, the plant will gradually weaken and its food value decrease. Not only that, smut spores blow on the wind, and infect other plants. The only remedy is to root up the infected plants and burn them.

Nothing pleases plant pathologists more than to find a nicely diseased plant. After a morning spent searching for smutted plants out on the farms, Doctors Graham Farrell and Jackson Kung’u are amused to spot a case back in the city. Here it is on a highway verge near the National Agricultural Research Laboratory in Nairobi. Smut lives up to its name and turns the flowering stems a sooty black. The fungus gradually weakens the plant and reduces it in mass and nutritional value.

*

My job on the smut quest was to hold the clip-board and the other end of the measuring tape while we sampled farm plots. Our third, and most essential team member, (in fact he was the real team leader) was Njonjo. He was the one who heroically drove us up and down the hilly Kikuyu lanes that had recently been ravaged by torrential El Nino rains.

As well as being one of NARL’s top drivers, Njonjo was himself a farmer, and so had a vested interest in getting to the bottom of the smut infestation. Since Graham’s Kiswahili was a bit rusty, and many of the older farmers preferred to speak Kikuyu, Njonjo provided them with on-the-spot lectures on what they should do with their smut-infected plants. He also talked our way onto every farm, where we welcomed in with huge courtesy, despite arriving uninvited.

Njonjo and Margaret the farmer. She was busy making compost when we arrived on her farm.

This farmer was so grateful to be told about his smutted Napier Grass he presented us with some sugar cane. We also came home with chickens, maize cobs and bags of pears

*

One of our tasks on the farm was to sample farmers’ Napier Grass plots to see how far they were infected, and to what extent the affected plants had lost mass. Njonjo organised a team of unemployed lads to help with the sampling.

Before the cell-phone revolution of recent years, farming information was hard to come by. Here Njonjo delivers his Smut Lecture to an impromptu gathering of smallholders who have spotted our arrival in their district and want to know what we are up to.

*

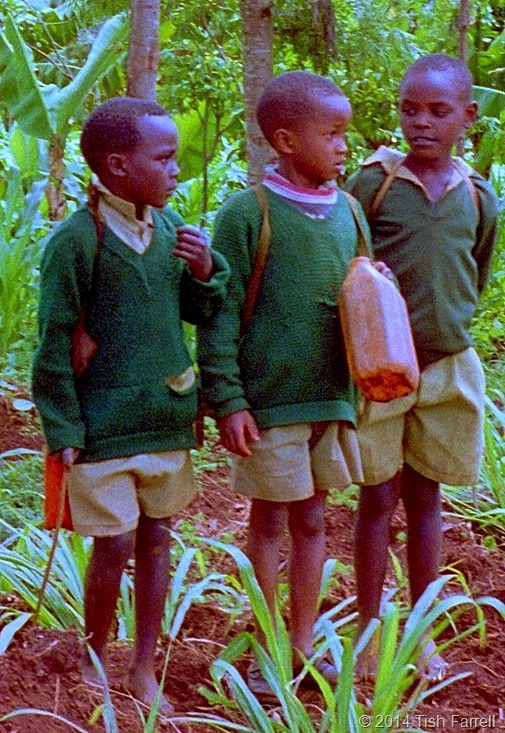

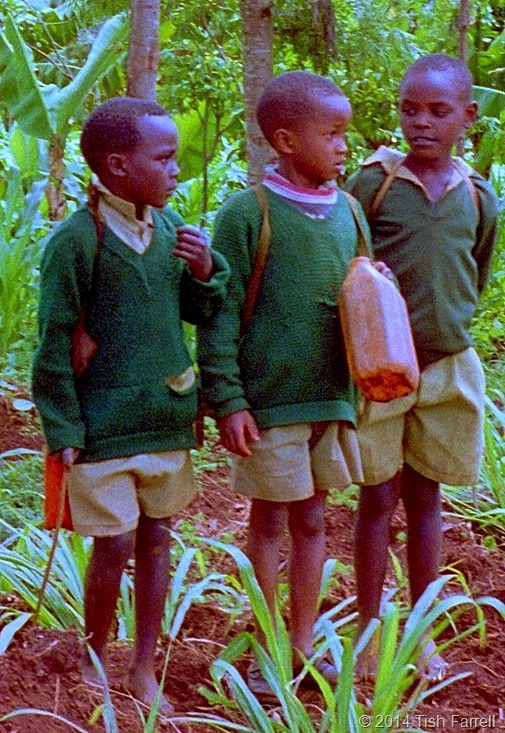

And here are three good reasons why Kenyans work so hard…

…education, education, education.

© 2014 Tish Farrell