In the last post I queried the large perforations to be found in the tops of some Derbyshire stone gate posts or stoops. I thought they made handy viewfinders, but could find no other explanation. Then I found some more photos I’d taken at Callow Farm. These are a pair – one with a partial orifice, the other without.

And it’s at this point things may become as clear as Derbyshire mud. But I have found an explanation. The only problem is I don’t wholly understand it.

It comes from a worthy volume published in 1813 and available for free from Google. (How I hate it that they have laid claim to all the old books in the universe, but how I love being able to access such works without leaving my desk, this despite the fact that much of the scanning is often execrable.)

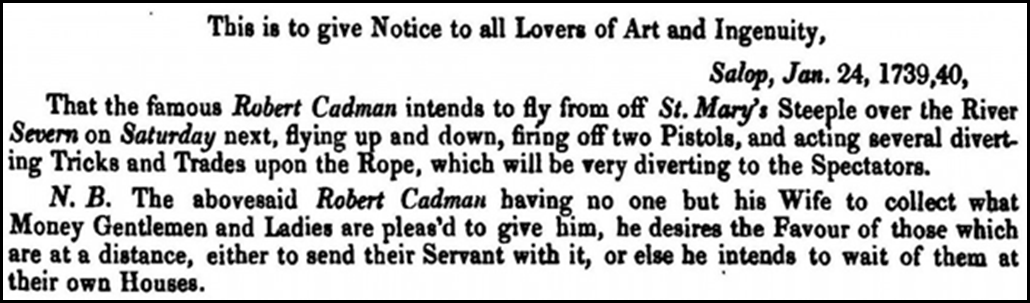

The book in question is volume 2 of General View of the Agriculture of Derbyshire by John Farey senior, Mineral Surveyor of Upper Crown Street, Westminster. This is what he says. I’ve increased the font in hopes comprehension might strike:

Anciently, the Gates in the Peak Hundreds were formed and hung without any iron-work, even nails, as I have been told; and some yet remain in Birchover and other places, where no iron-work is used in the hanging: a large mortise-hole is made thro’ the hanging-post, perpendicular to the plane of the Gate, at about four feet and a half high, into which a stout piece of wood is firmly wedged, and projects about twelve inches before the Post; and in this piece of wood, two augur holes are made, to receive the two ends of a tough piece of green Ash or Sallow, which loosely embraces the top of the head of the Gate (formed to a round), in the bow so formed : the bottom of the head of the Gate is formed to a blunt point, which works in a hole made in a stone, set fast in the ground, close to the face of the Post. It is easy to see, by the mortise-holes in all old Gate-Stoops, that this mode of hanging Gates was once general.

From this it seems clear that any iron hinges and latches were later additions to such old stoops. John Farey goes on to praise this kind of improvement:

A great contrast to these rude Gates, is exhibited, on the Farm of Mr. Thomas Harvey of Hoon Hay, who has four sets of hooks and catches, all adjustible by nuts and screws, fixed in his Gate-Posts, which are very stout, in the line of a private and bridle Road thro’ his Farm ; so that from whichever quarter the wind may come, in blowing weather, the Gates can readily be shifted, so as to be shut too by the wind, instead of being forced open thereby : there is also a screw for adjusting the top thimbles of these Gates, for making them shut more perfectly.

So there we have it – a loopy length of ash or willow used to do the job of a gate, though I still can’t quite picture it. But then instead of wondering about that, I found myself distracted by Mr. Farey’s genuine enthusiasm for more efficient gatery with all its iron trappings.

In this modern era we all assume a well functioning gate is a good thing – guarding property, keeping out vagrants and cold callers. But this notion of privately controlled land is fairly new. And to my mind it has had every one of us hoodwinked. Simon Fairlie puts it succinctly at the start of his very enlightening essay A Short History of Enclosure in Britain from The Land magazine:

Over the course of a few hundred years, much of Britain’s land has been privatized — that is to say taken out of some form of collective ownership and management and handed over to individuals. Currently, in our “property-owning democracy”, nearly half the country is owned by 40,000 land millionaires, or 0.06 per cent of the population, while most of the rest of us spend half our working lives paying off the debt on a patch of land barely large enough to accommodate a dwelling and a washing line.

He then explains that from Saxon times, and continuing under Norman rule into the Middle Ages, the Open Field System was the norm. It was also the norm in much of Europe until modern times, wherein each family had its own plot within a communally managed ecosystem.

The notion of one man possessing all rights to one stretch of land would have been unthinkable to British medieval smallholders. The king or lord of the manor owned an estate, but not in the way we understand ownership. The peasant population also had rights and, at specified times of the year, could graze stock, cut wood or peat, draw water or grow crops on various pieces of land, often in a number of different places. English farmers also met twice a year at the manor court where land management issues were discussed, and those taking more than their fair share of communal resources challenged.

The benefit of the Open Field System is explained as follows:

A man may have no more than an acre or two, but he gets the full extent of them laid out in long “lands” for ploughing, with no hedgerows to reduce the effective area, and to occupy him in unprofitable labour. No sort of inclosure of the same size can be conceived which would give him equivalent facilities. Moreover he has his common rights which entitle him to graze his stock all over the ‘lands’ and these have a value, the equivalent of which in pasture fields would cost far more than he could afford to pay. CS and C S Orwin The Open Fields, Oxford, 1938

A group of peasant farmers could also share equipment such as a good plough and a full team of oxen to haul it, a facility that would benefit them all. One herdsboy could supervise the daily grazing of the community’s cattle, taking them out after family milking, bringing back in for evening milking at their individual homesteads, so leaving farmers free to carry out other income producing pursuits. Everyone’s sheep could also be driven out to the common moorland to graze, each animal identifiable to their owners by a sheep mark.

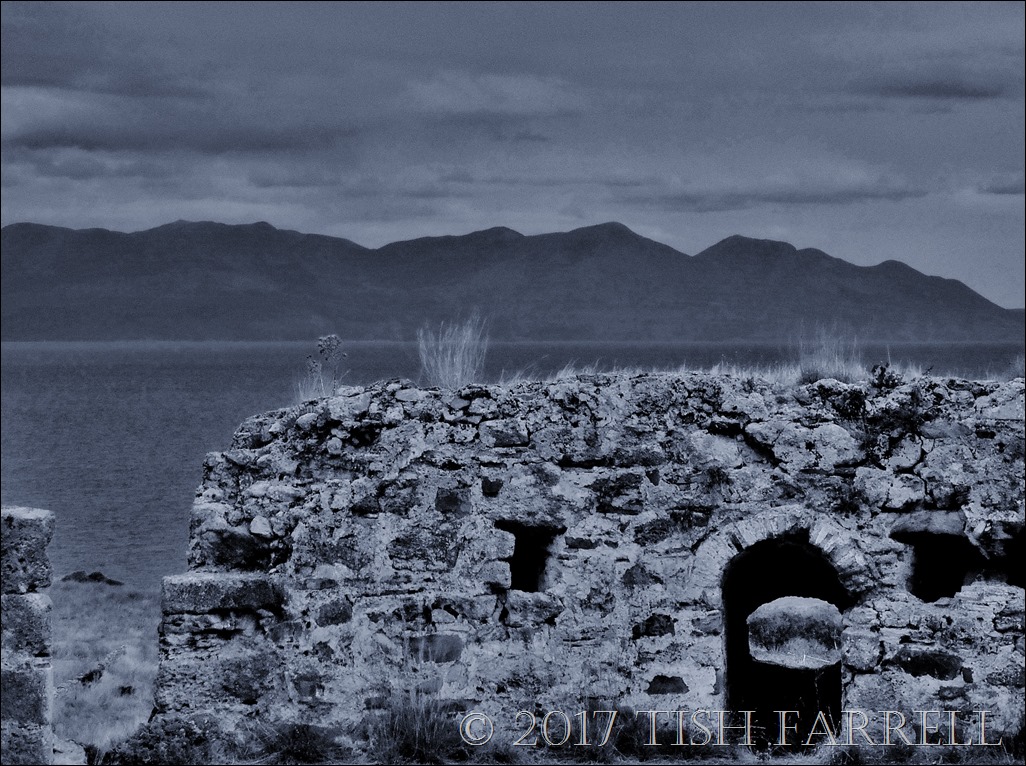

Somewhat strangely I have learned that the sheep mark of my Callow Fox ancestors was still in existence in 1930s, when the fiery right-to-roam campaigner G H B Ward, editor of the Sheffield Clarion Ramblers’ Handbooks went to interview my great uncle Robert Fox about the history of the Callow Foxes. Ward visited him in his cottage at Foolow and there saw the sheep mark belonging to an earlier Robert Fox (1780-1863), who used it to mark the horns of his sheep communally grazed on the Longshaw pasture. Enclosure took place there during the early 19th century, the Inclosure Act commissioners awarding the Duke of Rutland nearly 2,000 acres. And so the former sheepwalk used by William and Sarah Fox of Callow during the 18th century, and by their son George and grandson Robert into the early 19th century was turned into the headquarters of the largest grouse-shooting estate in the Peak District (David Hey The History of the Peak District Moors).

For nearly a century this former common land was policed by gamekeepers, and the general populace denied age-old rights including access to paths and bridleways. It was only with the mass trespasses of ramblers like G H B Ward during the early 20th century that the countryside began to be opened up once more. One cannot help but cheer when one learns that the decline in Rutland fortunes led to the sale of the estate in 1933. Ramblers and other members of public raised the necessary funds to buy the park and then handed it over to the National Trust. Sheffield Corporation bought the moors, which are now part of the Peak District National Park. Humanity is now free to roam there once more, as we saw on our recent visit – hundreds of families striding out in the fresh upland air.

The fact remains though that Britain’s big landowners exploited the Inclosure Acts to enrich themselves by taking for their own use alone (and still hanging on to them) thousands of acres that were once communally used for centuries by their tenants. But I leave the last words on the Commons land rights to Simon Fairlie. At the risk of sounding totally reductionist I contend that this is how we ended up where we are now; the wretched state of the planet; and the current tax-haven millionaires’ mortal fear of any notion of communal rights or shared resources. If we continue to let such people control and grow rich on resources which should benefit all – more fool us.

Britain set out, more or less deliberately, to become a highly urbanized economy with a large urban proletariat dispossessed from the countryside, highly concentrated landownership, and farms far larger than any other country in Europe. Enclosure of the commons, more advanced in the UK than anywhere else in Europe, was not the only means of achieving this goal: free trade and the importing of food and fibre from the New World and the colonies played a part, and so did the English preference for primogeniture (bequeathing all your land to your eldest son). But enclosure of common land played a key role in Britain’s industrialization, and was consciously seen to do so by its protagonists at the time.

copyright 2018 Tish Farrell