Some of you will have already read the essay below. It won first prize in a Quartos Magazine competition years ago. The magazine is no more, but I’m posting the piece again for those of you in need of a long, soothing wallow beside an African beach. Enjoy!

Going to the Dogs on Mombasa’s Southern Shore

It’s a dog’s life on Tiwi Beach, the white strand where ocean roars on coral and trade winds waft the coconut palms; and where, best of all, as far as the local canines are concerned, there are quiet coves sparse in holidaymakers. It means they may do as they please. After all, it is their own resort, and every morning they set off there from the beach villages along the headland, nose up, ears blown back in the breeze, ready for the day’s adventures.

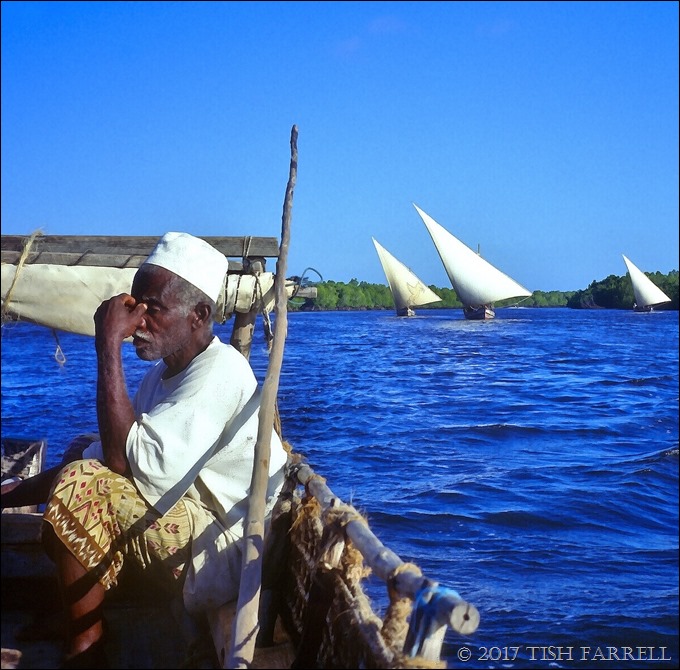

But the dogs are not churlish. They can take or leave the odd pale human wrestling to right his windsurfer on the still lagoon; ignore the sentinel heron that marks the reef edge beyond; pay no heed to the etched black figures of the Digo fishermen who search the shallows for prawns, parrot fish, or perhaps a mottled lobster or two.

But in this last respect at least, the dogs are smug. For the fishermen come down to the beach only to make a living. And when they are done hunting, they must toil along the headland from beach village to beach village, then haggle over the price of their catch with the rich wazungu who come there to lotus eat. Hard work in the dogs’ opinion.

The dogs know better of course; know it in every hair and pore. And each morning after breakfast, when they take the sandy track down to the beach, they begin with a toss of the head, a sniff of the salt air, a gentle ruffling of the ear feathers in soft finger breezes. Only then do they begin the day’s immersion, the sybaritic sea savouring: first the leather pads, sandpaper dry from pounding coral beaches, then the hot underbelly. Bliss. The water is warm. Still. Azure. And there can be nothing better in the world than to wade here, hour on hour, alongside a like‑minded fellow.

There’s not much to it; sometimes a gentle prancing. But more likely the long absorbing watch, nose just above the water, ears pricked, gaze fixed on the dazzling glass. And if you should come by and ask what they think they’re at, they will scan you blankly, the earlier joy drained away like swell off a pitching dhow. And, after a moment’s condescending consideration, they will return again to the sea search, every fibre assuming once more that sense of delighted expectation which you so crassly interrupted. You are dismissed.

For what else should they be doing but dog dreaming, ocean gazing, coursing the ripples of sunlight across the lagoon and more than these, glimpsing the electric blue of a darting minnow? And do they try to catch it? Of course they don’t. And when the day’s watch is done, there is the happy retreat to shore ‑ the roll roll roll in hot sand, working the grains into every hair root.

And if as a stranger you think these beach dogs a disreputable looking crew, the undesirable issue of lax couplings between colonial thoroughbreds gone native: dobermanns and rough‑haired pointers, vizslas and ridge‑backs, labradors and terriers, then think again. For just because they have no time for idle chit-chat, this doesn’t make them bad fellows: it’s merely that when they are on the beach, they’re on their own time. But later, after sunset, well that’s a different matter. Then they have responsibilities: they become guardians of the your designer swimwear, keepers of your M & S beach towel, enticing items that you have carelessly left out on your cottage veranda.

By night they patrol the ill‑lit byways of your beach village, dogging the heels of a human guard who has his bow and arrow always at the ready. And when in the black hours the banshee cry of a bush baby all but stops your heart, you may be forgiven for supposing that this bristling team has got its man, impaled a hapless thief to the compound baobab. It is an unnerving thought. You keep your head down. Try to go with the flow, as all good travellers should.

But with the day the disturbing image fades. There is no bloody corpse to sully paradise, only the bulbuls calling from a flame tree, the heady scent of frangipani, delicious with its sifting of brine. You cannot help yourself now. It’s time to take a leaf out of the dogs’ book, go for a day of all‑embracing sensation ‑ cast off in an azure pool.

And in the late afternoon when the sun slips red behind the tall palms and the tide comes boiling up the beach, the dogs take to the gathering shade of the hinterland and lie about in companionable couples. Now and then they cast a benign eye on you humankind, for at last you are utterly abandoned, surrendering with whoops and yells to the sun‑baked spume. They seem to register the smallest flicker of approval: you seem to be getting the hang of things.

copyright 2016 Tish Farrell

Edge