In 1992-1993, during the first years of Zambia’s multi-party democracy, we were posted to Lusaka, Zambia’s capital. Graham was charged with organising the distribution of European Union food aid to drought-stricken Zambians. (Part 1 is HERE and part 2 HERE and part 3 HERE and part 4 HERE)

Early in April 1993 Graham has another upcountry mission, this time to check on the arrival of maize at the Ukwimi refugee settlement area near Petauke, Eastern Province. The initiative, in an area north of the Mozambique border, is managed by the Lutheran World Federation, an organisation overseeing some 25,000 refugees in 73 villages spread over 300 square kilometres, an area that also includes several indigenous Zambian communities.

The incomers are village farming folk who have fled the civil war in their own country. Many among them share both language and cultural traditions with Eastern Province Zambians (i.e. communities historically divided by colonial map makers). At Ukwimi they are settled on parcels of land and given every assistance to become self-sufficient. In April 1993, with peace negotiated between Frelimo and Renamo forces, most recent cross-border arrivals in Ukwimi have been driven there by hunger.

*

It’s a 400 kilometre drive to Ukwimi HQ*, and another Monday morning appointment. We set out on Sunday at midday, leaving Lusaka on the Great East Road. The sky is overcast and it’s rather cool. As we pass by large dairy farms, among them Waterfall Farm owned by mining conglomerate Lonrho, the sight of green fields with Friesian cattle tells the brain we’ve somehow been flipped to Cheshire in the English Midlands.

But no. Now there are here-and-there banana thickets, palm trees with swollen boles and dishmop tops. And now we’re in bush country and the road stretching out. And now there are no other vehicles, but there are people, and we soon find that Zambians have many uses for highways beyond driving on them. We begin to see many people carrying palm fronds. It is Palm Sunday and the devout are walking down the middle of the road. And why not choose a smooth path.

Young lads sit on the road edge, leaning back, hands on the tarmac. They simply seem to sit and sit.

At Changwe there is a roadside trading centre with a few stores and a smart hacienda style bar and restaurant. We pass a bicycle race there.

At one point we bowl over a crest in the road and come on a big church gathering, filling both carriageways. People are singing and drumming. The crowd parts like magic and with great good humour, they wave us through.

*

Bush country flanks the asphalt, tall grasses on either hand and beyond them glimpses of shaggy thatched roofs, clusters of dwellings under thorn trees, small plots of maize. In places where the bush meets the tarmac there are hand-painted signs announcing the presence of bus stops, the gates to small farms: Mulenga, Mulaliki, Mulawzi; to the local medicine man.

We are travelling along a low ridge, to the south the land falls away in lightly wooded plains; to the north is a spine of blue hills. There are road-side stalls selling pumpkins and squashes of all shapes and sizes. There are wigwams of sugarcane, neat cords of firewood, sacks of charcoal. A woman walks by with a large zinc bath on her head. As she stops to adjust the load, a wave slooshes over the edge. The sight takes my breath away. I feel my spine contract.

And still there are few other moving vehicles along the road although we see many stranded broken ones.

Now the countryside is more hilly and densely wooded. There are roadside flowers, deep yellow daisies, pale yellow hibiscus, and a plant that looks like broom (also yellow). The villages have little thatched gazebos on the top of knolls with seats so you can look out to the blue hills. Meanwhile, the road that was good is not so good. There are big potholes, and to add to the driving confusion, some are filled with red dirt and others not. Where the road cuts through rock, it is carmine red and glinting with quartz.

We cross the broad expanse of the Luangwa River between wooded gorges. There is a suspension bridge opened in 1968 by former President Kenneth Kaunda. It looks sturdy enough, but a sign instructs drivers that only one vehicle at a time may cross, speed limit 10 kph. And so we cross.

About 50 km from Petauke we drive through a small village and fail to stop at the police check point. There is no one manning it. But ahead a khaki figure dashes from a roadside hut and waves us back. My heart sinks. We’ve had some uncomfortable moments at Kenyan checkpoints. But the young officer is charming. He apologises for not being in the road where we would have seen him. He had been growing too hot standing there, he says. We can see his point, but he still wants to see some I.D.

As Graham fumbles with his brief case, trying to find something that might serve, he says he works for the European Union. Ah, says the policeman, the man with the yellow maize. Some of your trucks have already gone through.

Graham says he is going to Petauke to check on their arrival. The officer smiles broadly and asks Graham for his name, salutes me with a “Madame” and bids us farewell, all without need of paperwork.

Further on at the turn for Petauke there is another road block. This time we are questioned by a young man who is clearly not a policeman. He tells us he is acting on his brother’s behalf. “Just to be friendly”, he says, “my brother needs to know who you are.” He is happy with Graham’s business card, finally retrieved from the brief case.

Now the roadside shopping opportunities include furniture, items parked in splendid isolation in the bush – a bed, a dining table, a row of Adirondack chairs.

Most striking of all is a lone Welsh dresser – the full deal, cupboards below, shelves above. There it stands, surrounded by elephant grass, challenging me, like one of the White Queen’s six impossible things before breakfast. And I wonder from what colonial or mission original was this piece so faithfully copied? And who does its maker think will buy it, here on the road to Petauke where so few people with the means to transport it seem to pass?

I’m still wondering when we check into the Nyika Motel and are shown to our bungalow. The bedroom walls are turquoise with orange paintwork, the chandelier green with most of its drops missing, curtains blue, the bedspread blue and black nylon, dark green cloths on the coffee table and sideboard – a colour scheme to jangle the nerves. But it does not matter. The place is scrupulously clean, with plenty of hot water, although we have to improvise a bath plug.

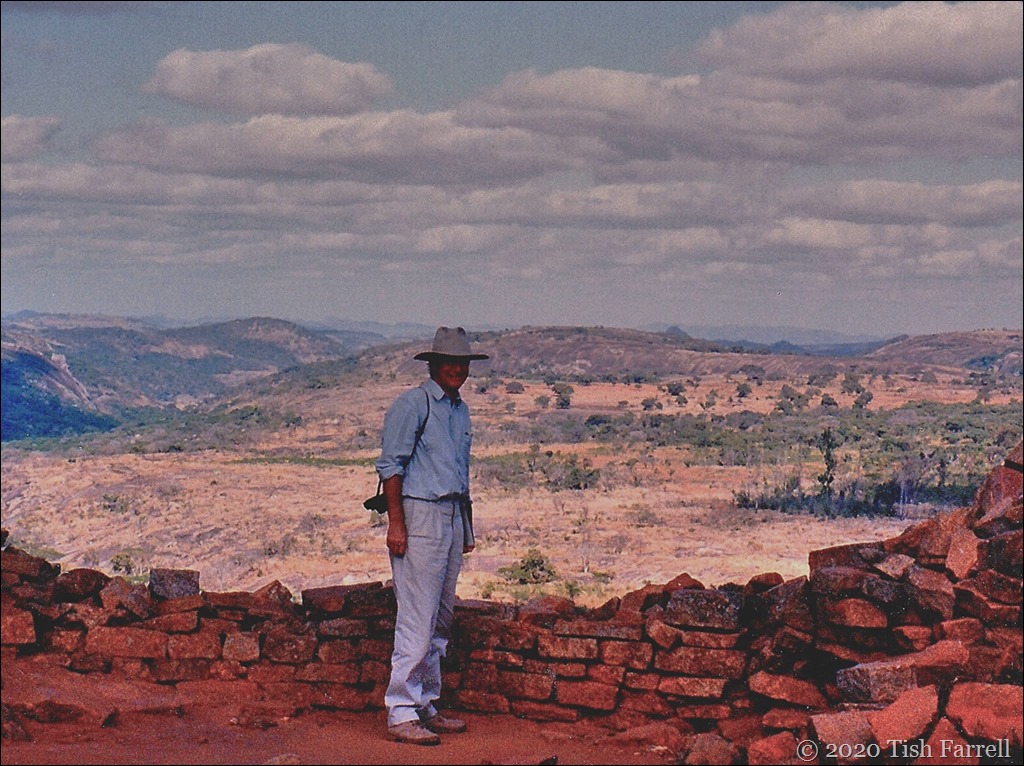

By now, the late day sky has seen off its gloom. There are magnificent cumulus cloud formations against the blue. We sit on the doorstep and watch the sun go down over the bush country, strange rocky outcrops to the south. There are rufous swallows, drongos, mousebirds, the bubbling call of the water bottle bird. The crickets tune up. There is lightning, wind in the thorn trees. I’m so glad to be there.

Copyright 2024 Tish Farrell

*Ukwimi HQ is now a Trades Training Centre for Zambians, the refugee centre no longer needed.