It seemed the greatest gift for this nosy writer when Graham said I could go with him to survey the Kikuyu farms just north of Nairobi. Yes, yes and yes. I would be delighted to look for smutted Napier Grass. And hold the clipboard. And manage one end of the tape measure.

We were all set then, along with Njonjo, senior driver for the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute, where Graham’s crop protection project was based.

It was the time just after the late 90’s El Nino rains. The Rift escarpment roads were terrible, many of them washed away. In other places great chasms had opened up, or the roads were strewn with boulders brought down the hills by flash floods. But this was also home territory for Njonjo. He had ancestral land there. A farmer then, when he was not employed as a driver. He anyway handled the Land Rover with great skill, and astonished us, too, by simultaneously negotiating giant pot holes and spotting plots of smutted grass growing many metres from the roadside behind kei apple and winter jasmine hedges.

Njonjo and Graham

*

Trading centre after El Nino rains

*

*

Of course, after a fine spell, the roads baked hard into gullies and corrugations. This next photo shows one of the Rift Valley lanes on the edge of the escarpment. You can just make out the valley bottom through the far haze:

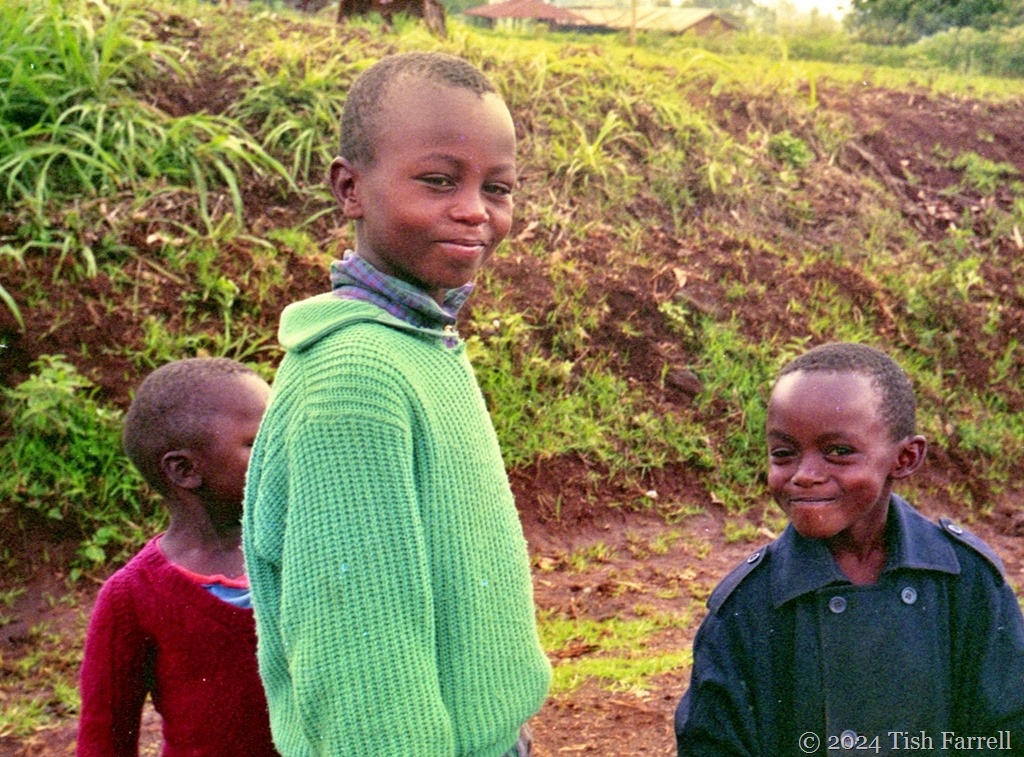

I don’t recall why we were all out of the Land Rover at this point. Probably Njonjo was asking directions. Even locals have problems finding their way across the ridges. Anyway, this was the moment I met this lovely young man:

*

Small-holder farms at Escarpment, in the Rift’s shadow, Mount Longonot in the background

*

As we jolted and slid along the country lanes, Graham was using a GPS to select farms at random. When a location was chosen, Njonjo then took further charge of operations and went to find the owner of the farm, and talk them into admitting a couple of wazungu , who would like to look at their Napier Grass.

Over the weeks of the survey it became a matter of pride that no one turned us away. In fact the opposite was often overwhelmingly true. Wherever we went, we were met with great courtesy, mugs of tea and presents of farm produce: plums, pears, sugar cane, a cockerel. We had brought useful information that must be reciprocated. Njonjo was particularly adept at fending off serial invitations to lunch, and did so without us seeming too rude. Otherwise the job would never had been done.

This farmer gave us sugar cane

*

One chilly morning Mrs. Njuguna served up mugs of hot chocolate before we went to examine her napier grass plot

*

Napier Grass (foreground in both photos) is an essential animal food crop for small-holder farmers who zero graze their stock. Zero graze means they have no access to pasture, but grow plots of grass wherever they have space, including on roadside verges, and then crop and deliver the grass to their animal pens. (Commercial tea gardens in the background). Most farms (shambas) are on ancestral land that has been subdivided down the generations and may be only a few acres or less.

*

By now you’re probably wondering what Napier Grass smut looks like. You will also have gathered that in this context, smut has nothing to do with off-colour jokes or questionable practices. (That said, everyone found it hugely amusing that Graham was doing a part-time doctoral thesis on smut). It is in fact a fungal disease that attacks grasses, including maize and sugar cane. On Napier Grass it becomes visible when the plant begins to flower; the florescent parts look as if they have been dipped in soot.

Two happy plant pathologists: Graham with Dr Jackson Kung’u admiring smutted grass growing on a road reserve in Nairobi, as spotted across a busy dual carriageway by Njonjo.

*

The diseased grass isn’t apparently harmful to the animals that eat it, but there are serious implications for farmers who rely on it for zero grazing. In time, smut weakens the plant and so less and less leaf mass is produced. The spores spread on the wind, although Graham thought the most likely source of infection was due to farmers unknowingly giving cuttings of infected plants to their neighbours. The only solution is to dig up the plant and burn it.

Farmers, predominantly women, were keen to hear anything and everything Graham could tell them. Impromptu roadside smut seminars became a feature, Njonjo providing lectures in Kikuyu or Swahili for those who did not speak English. Graham also distributed information sheets. We never seemed to have enough!

*

On some of the farm visits, it was inevitable that Graham would be consulted about other plant diseases that farmers had noticed. Here there’s some problem with the fruit trees.

The farmer’s daughter watches us. Her father had handed her one of Graham’s smut information sheets: the school girl in the family…

*

The Kikuyu uplands are mostly 5-6,500 feet above sea level, the settlements strung out along ridges. Although at the tropics, early mornings and evenings can be cool, and especially in June and July, when there may also be fine rain and fog. Some of the highest settlements at around 7,000 ft are in the frost zone, the landscape’s bleakness, with bracken growing along the roadside, reminding me of Scottish uplands.

*

All in all, Graham’s smut survey was among the highest highlights of our seven year stay in Kenya. Although not everyone was always keen to speak to us:

copyright 2024 Tish Farrell

Lens-Artists: This made me smile Ann-Christine is making us all smile with this week’s theme.