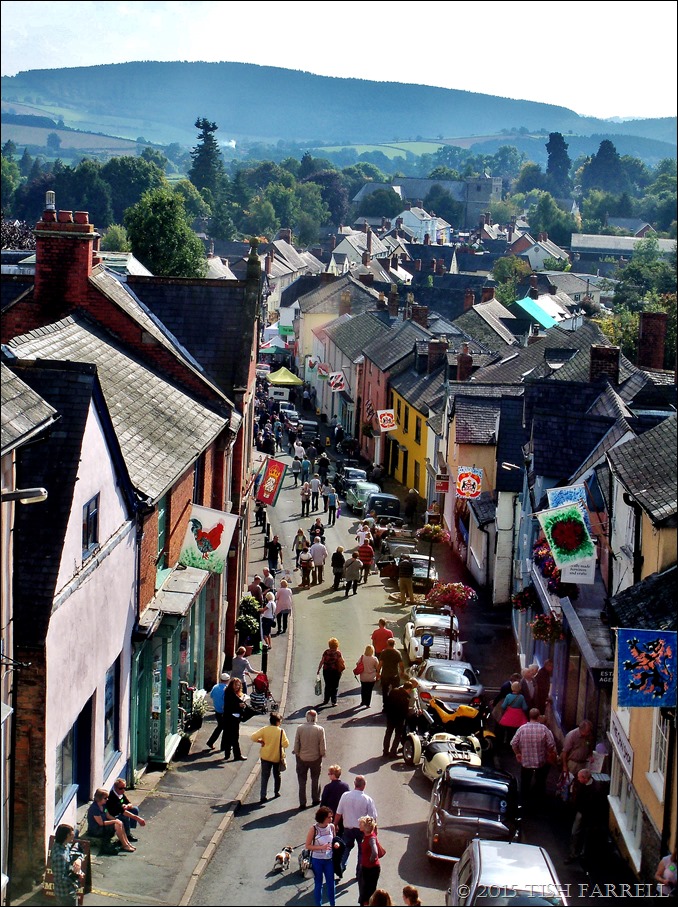

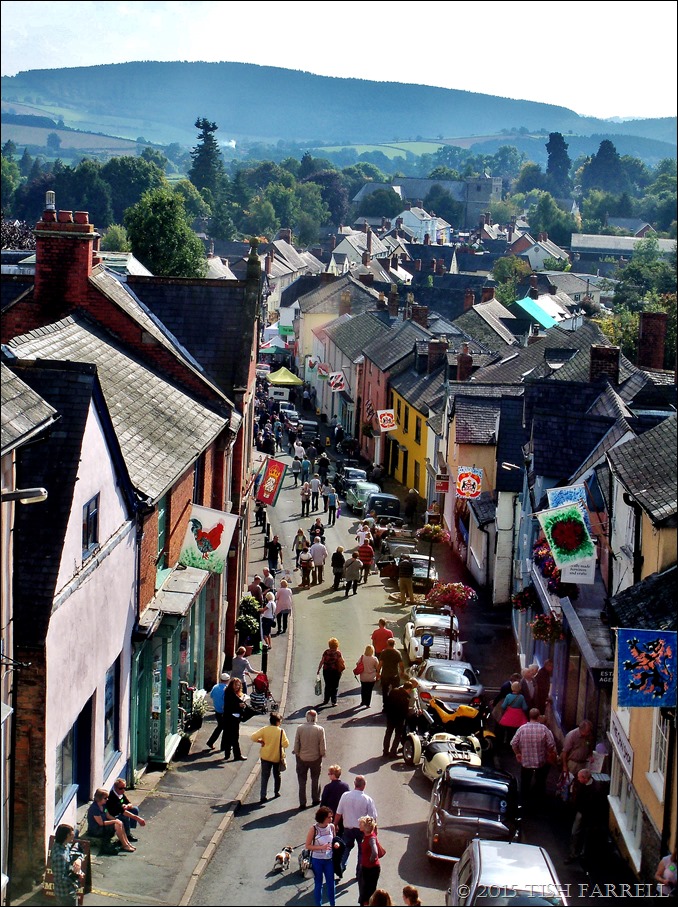

…to the Bishop’s Castle Michaelmas Fair, to be precise. And not only did summer come back to us after a week of dreary coldness, it was warm, and bright and stayed ALL day.

The fair was to be found in every quarter of the town, from St John the Baptist Church at the bottom of the hill to the Three Tuns Inn at the top of the hill, and with here-and-there enclaves in between.

This shot of the High Street looking towards the church was taken from the window from the Town Hall. This handsome civic building (coming up next) has recently been refurbished and doubles up as the town’s market. This year it is celebrating its 250th birthday…

Wending on upwards past the Town Hall, and bearing to the right, you come to the Three Tuns Inn. It is one of Shropshire’s real ale treasures. They’ve been brewing beer there since 1642, so they must be doing something right. It’s apparently the oldest licensed brewery in Britain, but…

…it is not the only micro-brewery in this small town. For those who don’t care to climb hills for a pint, you can sample the Six Bells’ Cloud Nine, a piece of real ale heaven, down on the corner of Church Street.

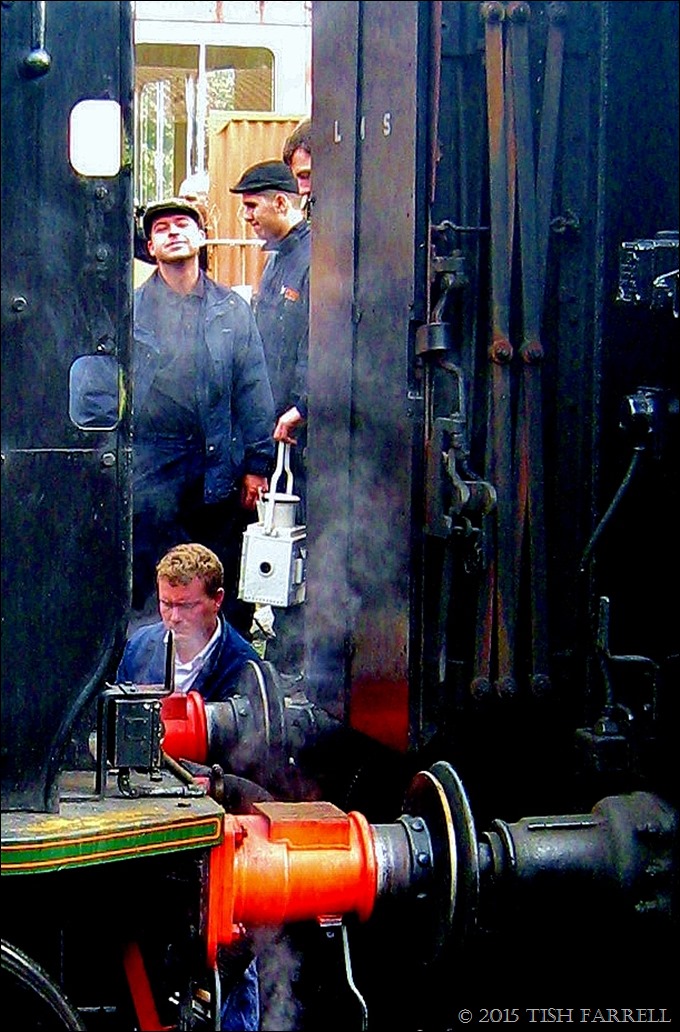

A nice set of wheels, chaps?

Which brings me to another big excitement of the day – the Michaelmas Fair Parade. Not only did we have beer, bubbles, folk songs, indie rock, ballads and wall to wall bonhomie, there were also classic cars, tractors, and steam powered vehicles. But before all that we had…

Oh ye, oh ye. Make way for the Bishop’s Castle Elephant…

He’s called Clive, and was created by local maker, Bamber Hawes, with help from the town’s Community College students. Bishop’s Castle artist, Esther Thorpe designed Clive’s ‘skin’, and the primary school children did the printing. And if you want to know why Bishop’s Castle has an elephant on parade, I’ll explain later.

For now, watch your toes, here comes a huge steam roller…

…and Peterkin the Fool on his stilts. He nearly trod on me…

…and then there were tractors (I remember when farmers had these)…

…and cool types in classic cars…

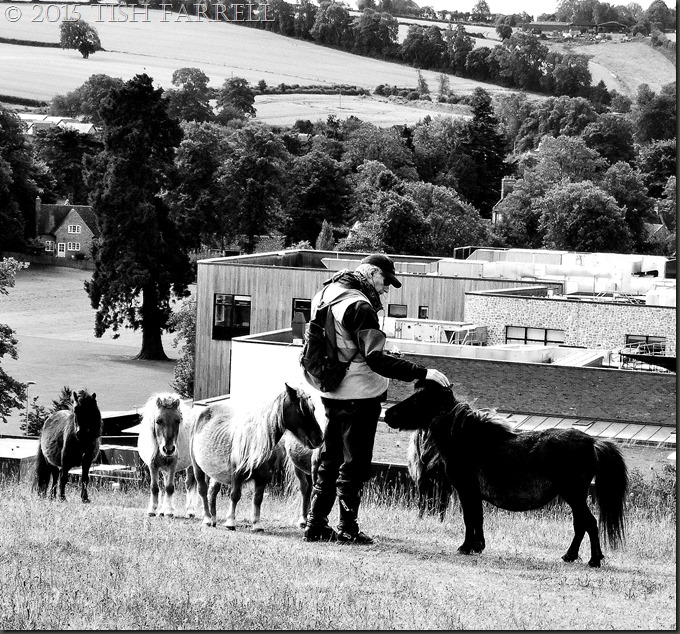

Then there were owls to hold, alpacas with socks to sample, more bubbles from the world’s tallest bubbleologist. We were so excited we had to resort to the Church Barn for soothing tea and brownies. After all, no good English ‘do’ is complete without afternoon tea…

And now as promised, a bit of a yarn about Clive the Elephant. It’s a tale of dirty dogs and political shenanigans of 250 years ago. These were the days when Bishop’s Castle was a notorious Rotten Borough. There were two Members of Parliament, and only 150 people with the right to vote. How people cast their vote was a matter of public record, and this meant voters could be intimidated into supporting particular candidates.

Enter Shropshire-born Robert Clive, aka First Baron Clive aka Clive of India. He was on a mission to build political power, and had the money to buy it. He had used his position in the (also notorious) British East India Company not only to found the British Empire in India, but also to return from the Sub-Continent with shiploads of loot. He then set about buying votes for the men he wished to have as MPs. As part of his scheme of self-aggrandizement he added an elephant to his coat arms. It symbolized India, and his personal power. Today, a stone carved version may still be seen in Bishop’s Castle’s old market place…

The reason Clive wanted power was so he could set about reforming the East India Company, and get rid of corruption in the administration. This did not come to much. Pots and kettles come to mind here. He died at the age of 49. All sorts of allegations were made as to cause of death – that he stabbed himself, cut his throat with a penknife, died of an opium overdose. It seems he suffered from gallstones, and was using the drug to deaden the pain. A more recent interpretation of events concludes he died of a heart attack due to the over-use of opium.

However you look at it, this is not a good elephant story. Far more heartening is the fact that during World War 2, a circus elephant was looked after in the town, and lived quietly in the stable of the Castle Hotel.

Finally a few more scenes of fun and jollification. I should also say that if I didn’t live in Much Wenlock, Bishop’s Castle would be the place I would most like to live – no longer a rotten borough, but a place bursting with community good spirits…

copyright 2015 Tish Farrell

Even though it was a Saturday, I’m linking this to Jo’s Monday Walk

Please visit her blog. There is no better place to be inspired to get out and about with your camera.