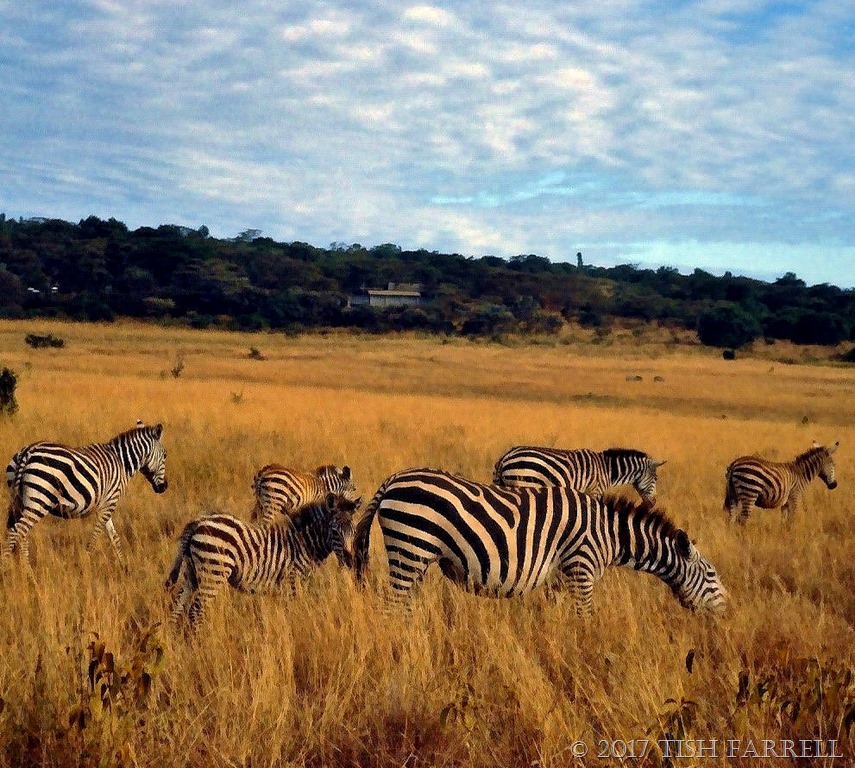

There are the experiences we had, and the ones we think we had: so many versions of the ‘truth’. And much like conscious memory, the Kodak negative from which this image comes, is much degraded; the colours distorted. I’ve had to do some de-saturating to reduce the negative’s livid cast. Not very successful, but the result, I think, is all my own ‘Out-of-Africa-nostalgia’ effect.

Naturally my writer-self loves the romance of this and related yarns of the old safari era. And yet these are not the real story. They never were. That’s one of the problems with nostalgia, particularly the Anglo-African variety. It’s usually a longing for something that never was. It was the kind of longing that brought British settlers of the gentry class out to East Africa in the first place. Anything would grow there, they said. Fortunes would be made. And until the predicted riches rolled in – from ostrich feather farming, flax, wheat, coffee and tea – the hunting potential for the sporting man (and sometimes woman) was limitless – herds of wild game from sky to sky, and a country full of cheap household servants and farm labourers. And all so handily available just when home supplies of both (animal and human) were on the wane.

Here’s a poster of the time, pre-1920, summing things up. The similarity to a Punch Magazine cartoon was apparently deliberate.

As railway advertisements go, this one truly takes the biscuit, and on so many fronts. Please note the very small print towards the bottom: ‘Arrival of the first Cook’s excursion and the result of carefully preserving the big game’. Also I’m not sure what the bipedal beast behind the train is meant to be. It looks like a bear to me. Perhaps he came with the aristocrats, captured on one of their North American shooting expeditions – also popular at the time.

So: elite settlerdom in East Africa seemed a fine idea. And as long as the European lower classes were kept out, the incomer Indian labourers and traders kept in their place (these mostly the survivors of the 18,000 ‘coolies’ imported from India in 1896 to build the Mombasa-Uganda Railway), and the local Africans did the field work for minimal pay while their own traditional hunting practices were outlawed, then, by Jove and St. George, it would be paradise on earth. The British East Africa Protectorate (Kenya Colony after 1920) was, and forever would be, a dedicated White Man’s Country. A lordly sporting estate writ large. The happy hunting ground of new white landowners who believed that only they, gentlemen (and under certain circumstances, gentlewomen) had the god-given right to hunt. All the game was theirs.

But hang on a minute. In this safari story the real protagonists are invisible, or overlooked, deliberately excluded; these, the many African hunters and expert trackers who facilitated the pursuits of their white overlords on the imperial safaris of the early 20th century; they who risked arrest for the crime of poaching if they dared to hunt for their own pot as their people had done for countless generations before the British invaded.

It is not for nothing that the settlers referred to their African workers as boys, reducing them to beings of little or no account. From such aristocratic notions of superiority and entitlement – a mind-set that persisted among many until Independence in 1963 – does the modern state of Kenya derive. In some ways little has changed. Ever since Uhuru, the post-colonial rulers (and with a similar sense of dynastic entitlement) have been intent on commandeering all resources for themselves, and ignoring the needs of those they rule.

*

But back to the aging photo of magnificent beisa oryx. It was taken nearly 20 years ago. The Farrells were, in the manner of Kenya’s well-honed, post-colonial tourism model, ‘on safari’; flown in a twenty-seater plane – out of Nairobi and into Lewa, winging left at Mount Kenya. Touching down on the airstrip cut from bush you could spot elephant and the strangely foreshortened view of Mount Kenya’s summit.

Our destination was a small tented camp in Laikipia, northern Kenya, a three night sojourn out in the wilds. I should say at once that when we stayed at the Lewa Downs safari camp it had not accrued the expensive, life-style look it has now, nor the uber-nouveau-colonial glamour of Lewa House and its secluded guest cottages. (Prince William apparently proposed to Kate Middleton while staying there as a family guest). In our day we had a big green tent, one of a dozen. There was a small shower room and WC attached, and the whole lot camouflaged by a thatched canopy. When the flaps were back we could lie in our bunks and gaze at miles and miles of Africa and inhale the sweet aromatic scent of thorn brush. The accommodation was simple and functional although we naturally thought a tent with its own clean, running water and a flush loo was a great luxury. But then as many travellers in Africa before us, and in pursuit of our own pleasure, we chose to ignore any moral issue associated with this provision. The camp was otherwise low-key, mostly set up to attract birding photographers, and one of several similar small camps run by the East African Ornithological Society.

*

The camp we stayed in occupied a small corner of the Lewa Downs estate, once a colonial cattle ranch staked out from former Maasai grazing territory in 1922 under the British government’s post-war Soldier Settlement Scheme. The colonial administration’s plan at that time was to double the colony’s European population. Meanwhile the Africans’ side of the story was as follows. All Kenya’s indigenous peoples had to live on their allotted tribal reserves unless they were working for Europeans. They could not acquire land outside the reserves. All men over the age of sixteen had to wear the kipande pass book containing their work record. All Africans paid poll and hut taxes, which had just then been increased to recoup costs from the European war effort. Taxation also had the aim of impelling Africans into the labour market. Africans who had served in the Great War were not eligible for the new settlement land (10,000 soldiers, 195,000 porters of whom 50,000 had perished).

For Europeans, however, that it is to say for ‘men of the officer class’, there was on offer by lottery or at cheap rates, large blocks of land in the fertile Central Highlands and the Laikipia Plateau below Mount Kenya. Officials apparently believed that such men, newly returned to civilian life and most with little or no practical farming experience, would in an untried African environment, produce export quantities of cash crops. This trade in turn would fund the upkeep of 600 miles of now largely purposeless, but very expensive Mombasa-Uganda railway that the colonial administration had built between 1896 and 1901. (Also known as the Lunatic Line).

The railway’s original purpose was to provide access to land-locked Uganda, then believed to be the future source of vast natural resources. There were strategic reasons too. In the last decades of the 19th century, during the big European land grab of Africa, relations with Germany had become increasingly scratchy, and especially over possession of Uganda. British paranoia raised the spectre of the Germans sabotaging the source of the Nile at Jinja in Uganda, thereby scuppering Britain’s major shipping lanes in the faraway Suez Canal which relied on Nile water. Once thought of, only a railway would serve to bring troops swiftly to the scene to defend the vulnerable head waters.

Africa 1914 (St. Francis High School website)

*

Twenty years later, these functions unrealised or redundant, only large-scale European settlement would make the best of a bad job. Along with this ‘House that Jack Built’ mode of thinking was the idea that veteran officers, used to handling men, would be well fixed to manage and ‘civilise’ (i.e. instil discipline in) African labourers, this despite knowing nothing of their employees’ traditions or way of life or their language. Also if things went wrong at some future time, an uprising for instance, the officer chaps would usefully know how to handle a gun and not be afraid to use it.

As I’m writing this, I’m thinking that it sounds like a very bad joke with a dollop of Wodehouse daftness thrown in. But this is how the British Empire did things in East Africa. They were not prepared to invest in indigenous Africans, but they were prepared to take a punt on the ‘right sort’ of Europeans of whose farming prowess they knew not one single thing.

*

Roll forward 96 years…

Today Lewa Downs is still owned by descendants of the Craig/Douglas families who began the ranch. But now, and in cooperation with local indigenous communities, and the Kenya government, the owners use their 62,000 acres not for farming, but to protect threatened wildlife. Among their wards are populations of black and white rhinos whose territory is watched over around the clock by vigilant rangers, and whose horns are defended from poachers by armed Kenya Police Reservists.

It is an award-winning, avowedly non-profit-making enterprise that has set out to demonstrate that up-scale tourism can serve both wild life conservation and local community development. Other funding comes from donation and sponsorship, and a big proportion of the total income is spent on community projects including clinics, education, water management schemes, and low-interest loans to kick-start women’s small businesses.

Anyone who stays at Lewa Conservancy can be guaranteed unforgettable experiences – the full-on African wilderness, magnificent game viewing in breath-taking country, the chance to see how some of the tourist dollars are being spent. There are bush breakfasts, night game drives, camel riding, and star bathing. It would seem to be the 21st century eco-socio-sensitive take on the self-serving champagne safaris of the 1920s and ‘30s when white hunters – John Hunter, Bror Blixen and Denys Finch Hatton et al – ran commercial shooting expeditions for the elite of Europe, India and America.

And while the trophies these days are photos and memories, and not elephants’ feet, tusks and antelope heads, and while the safari guests’ presence may help to fund laudable causes, and not the free-booting life-styles of maverick aristocrats and misfit adventurers, still the packaging of today’s safaridom evokes something of the old elitist romance. If we don’t watch out it clings like a parasitic infection and blinds us to the many ironies.

But have a look for yourself at what the Lewa Conservancy is doing for people and wildlife. The model is not without its critics. Other settler descendants have pointed out that big landowners who stayed on in Kenya after Independence have been increasingly under pressure to start sharing their acres if they were not seen to be doing something very useful with them. The Craigs and their management team seem to have come up with quite a solution. The safari story continues…

copyright 2018 Tish Farrell