Long ago when we lived in Kenya, we spent one Christmas on the Indian Ocean island of Lamu – a never-to-be forgotten, all too brief safari. We stayed in the roof-top quarters of an ancient merchant’s house in Shela Village, a thatched eyrie that, being open on three sides, allowed to us eavesdrop on all our neighbours. It was breezy too, the natural air conditioning more than welcome in December’s steamy heat.

Our first view of Stone Town, Lamu’s main settlement, was on Boxing Day when we were taken on a dhow trip out to the reef. It was a good introduction, sailing along the entire quay, hints of Sinbad magic.

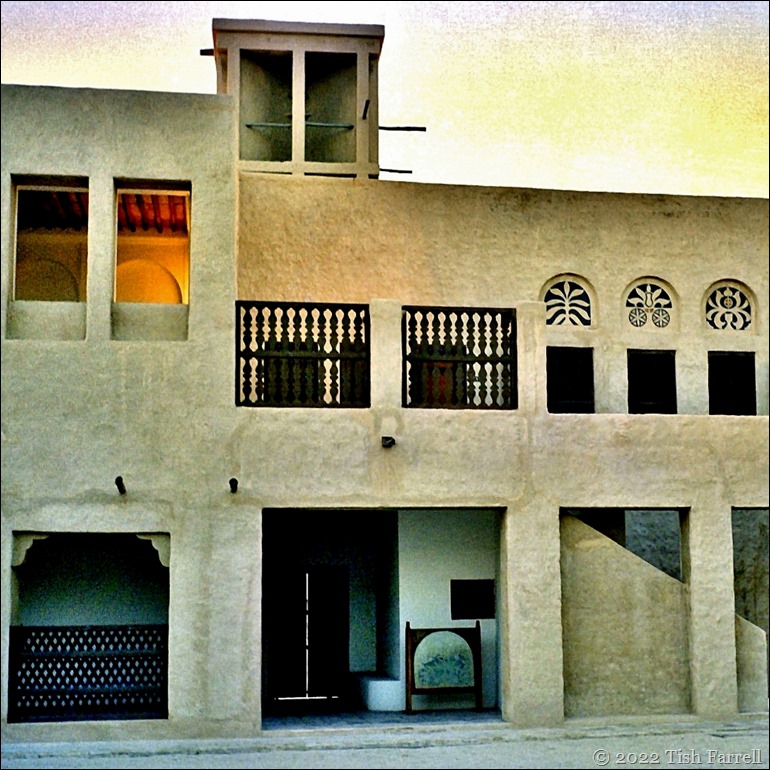

Lamu’s Stone Town is one of the best preserved Swahili towns on the East African coast, lived in for over 700 years. It is not one of the earliest by any means, nor the finest, but it has its own particular history as a one-time city state, ruled by its own sultan. Its wealth back then was built on the seasonal dhow trade with Arab seafarers. Now its residents make their living from tourism, fishing, boat building and farming. It is also a place of pilgrimage. Lamu is devoutly Muslim, and each year holds a five-day Maulid festival, celebrating the birth of the prophet, Muhammad.

For more about the Swahili people here’s a segment from an earlier post:

“You could say that Swahili culture was born of the monsoon winds, from the human drive to trade and of prevailing weather. For two thousand years Arab merchants plied East Africa’s Indian Ocean shores, from Mogadishu (Somalia) to the mouth of the Limpopo River (Mozambique), arriving with the north easterly Kaskazi, departing on the south easterly Kusi. They came in great wooden cargo dhows, bringing dates, frankincense, wheat, dried fish, Persian chests, rugs, silks and jewels which they traded with Bantu farmers in exchange for the treasures of Africa: ivory, leopard skins, rhinoceros horn, ambergris, tortoise shell, mangrove poles and gold.

By 700 AD many Arab merchants were beginning to settle permanently on the East African seaboard, and the earliest mosques so far discovered date from around this time. These new colonists would have married the daughters of their Bantu trading hosts and doubtless used these new local connections to expand their trading opportunities. Soon the African farming settlements were expanding into cosmopolitan port towns. Itinerant merchants and their crews would also have had plenty of chances to get to know the local girls. The weather served this purpose too. Between August and November the trade winds fail. Voyaging captains would thus put in to a known safe haven to wait for good winds. And while this was not a time to be idle, since boats had to be beached and the crew put to cleaning and sealing the underwater timbers with a paste of beef fat and lime, three months was a long time to be ashore and far from home… continues HERE

Main Street, Stone Town

*