Biswajit Dihidar captures the most beautiful images of his homeland on the Viewfound blog. This image I think is especially striking…

Heritage

Gazing into Hell’s Mouth at Plas yn Rhiw

Surely Plas yn Rhiw is too lovely a place for visions of Hell? The ancient Welsh domain on the road to Aberdaron has a benign and slumbering air; here are gentle and delicate spirits.And it is not simply in the subtle shapes of the garden’s planting or the soft hues and scents of fading flowers;

or in the cobbled paths and woodland walks where wild strawberries and ferns grow alongside fuchsias and hydrangeas;

or in the fabric of this old, old house whose stones reflect the end-of-summer sky and the steely blue-greys of the sea below.

Even the air around the house feels strangely soft. It is the kind of late September softness that makes you want to lie down in the grass and dream for days and years, listening only to insect hum and the chatter of sparrows. The setting anyway is blissful; all enclosed by woodland at the foot of Mynyth Rhiw Mountain, and embraced by the seeming sheltering curve of Hell’s Mouth Bay (Porth Neigwl). So now you have it, an inkling that the tranquil surface overlays some deeper, darker currents.

Hell’s Mouth lies on the southerly tip of Llyn Peninsula, overlooking the broader sweep of Cardigan Bay. The calm view from Plas yn Rhiw is transfixing. How can it have such a name? Yet watch this space and see a different scene. For when the south westerly gales come roaring in, this bay becomes a death trap. Over the years it is said that some thirty ships have been run aground, their holdfast anchors dragging before the driving storm. Wrecks include the Transit that foundered with a cargo of cotton in 1839. In 1840 it was the Arfestone carrying gold. An Australian ship was lost there in 1865, and in 1909 the sailing ship Laura Griffith was wrecked. And there is more.

Reel back to the 8-900s AD and Llyn was the scene of bloody raids. At this time the Vikings occupied coastal Ireland across the bay. Llyn was then part of the Welsh Kingdom of Gwynedd and Powys and its prominent position made it seem an easy target from over the Irish Sea. The Welsh, under Rhodri Mawr (Rhodri the Great 844-878 AD) fought valiantly to keep the raiders at bay, although accounts of the time attest to their terrifying attacks. But whatever the truth, the sight of a raiding party, sixty five ships strong, and coming fast into the bay must have truly chilled the blood. By the 10th century Llyn was still holding its own against Viking incursion, but only through constant vigilance. And this is where Plas yn Rhiw comes in. Local history has it that Meirion Goch, great-grandson of Rhodri Mawr, was instructed to build a fortified house at Rhiw and hold the coast against invasion. It is also thought that this stronghold occupied the site of the present house, although no provable traces have been yet been found. The descendants from this royal dynasty appear then to have occupied Plas yn Rhiw for the next thousand years, eventually adopting, in the English fashion, the surname Lewis. ![IrishSeaReliefmap[1] (2) IrishSeaReliefmap[1] (2)](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/irishseareliefmap1-2_thumb.png?w=386&h=480) The Llyn Peninsula is the finger of land above Cardigan Bay. Hell’s Mouth is due north of the ‘d’ in Cardigan. The port of Dublin in Ireland was founded by the Vikings, along with other coastal towns that they used as raiding bases. (Map: Creative Commons).

The Llyn Peninsula is the finger of land above Cardigan Bay. Hell’s Mouth is due north of the ‘d’ in Cardigan. The port of Dublin in Ireland was founded by the Vikings, along with other coastal towns that they used as raiding bases. (Map: Creative Commons).

*

The house we see today, then, has its own stories – cycles of re-building, abandonment, decay, renewal. Now , as a National Trust property, it is frozen in time; as if its last elderly inhabitants, the Keating sisters, have simply popped out to the shops and left you to gaze upon their hats and gloves, and recently received letters. But more of these sisters in moment. First a quick history of the house. The lintel over the French window is carved with the date 1634, which probably marks the re-modelling of an existing medieval house by the then owner John Lewis. In 1820 the house was further extended and the grand Georgian facade and a further storey added. But in 1874 the long connection with the Lewis family ended and the house was sold for the first time in its existence. The new owner then let it to a succession of tenants, and it was possibly one of these, Lady Strickland, who created the gardens. She apparently also introduced the first bath tub to the district. And there is a tale of a ghostly visitation during her tenancy – a drunken squire roaming the house in search of a drink (lost spirits perhaps?). But by 1938, when the house was once more for sale, it was in a sad state of repair. The nearby millstream had left its bed and was running through the hall, rotting the staircase, brambles blocked the front door and the garden was a jungle. Enter the saviours, Welsh conservationist and architect, Clough Williams-Ellis (creator of Portmeirion ) and his friends the Keating sisters.

In this newspaper photo of 1960 (www.rhiw.com/) we see Eileen, Lorna and Honora Keating at Plas yn Rhiw. It is down to them that Llyn does not have a nuclear power station. They bought up coastal land to prevent it, and than gave the land to the National Trust. They also opposed overhead power lines and caravan parks, and in 1939 Honora received an OBE for her work for the National Council for Maternity and Child Welfare. They were the daughters of a Nottingham architect who was killed in a traffic accident when they were small. Their 32-year old mother Constance was left to bring them up, and she ensured, among other things, that they received a good education. Every year from 1904 the family spent their summers in Rhiw. In 1919 they bought a cottage above Hell’s Mouth, and it was from here that they first saw Plas yn Rhiw. In 1934, after Constance became an invalid, the sisters settled permanently with her in Rhiw. There are tales of them shunting mother around the locality in a wheeled bed. By this time Plas yn Rhiw was abandoned, and although there were hopes of saving it, the owner could not be found. Then in 1938 a FOR SALE notice went up. Six hundred pounds was the asking price, and it was Clough Williams-Ellis who alerted Honora. He sent her a telegram: “Will you invest savings Plas”. She replied: “Yes, but haven’t got much.”

The sisters bought the house, along with 58 acres of land that were all that remained of the original estate. With Clough Williams-Ellis to help and advise, the restoration began, and the following year the Keatings moved into the house. They then set about buying back the estate’s former land, which they gave to the National Trust in 1946 in memory of their parents. The house was donated in 1952, although the sisters lived there for the rest of their lives, the last and youngest sister, Honora, dying in 1981. Inside, the house has no pretensions to grandeur, although it is filled with personal treasures – everything from fine Meissen figures to the cottage vernacular of a Welsh spinning wheel. Along with the family portraits and antique furniture are paintings by Honora who studied at the Slade, and also works by M E Eldridge, the often overlooked artist wife of the poet R S Thomas. (When Thomas retired from being parish priest at nearby Aberdaron, the Keatings leased to him Sarn Rhiw, a stone cottage in the grounds below the house).

The Yellow Bedroom

*

Honora’s room – alongside the Victoriana there is in the fireplace a c.1916 Royal Ediswan electric fire which operated by means of 250-watt bulbs. Beside the bed is an early Pifco Teasmaid.

*

Today the National Trust is continuing to restore the house while staying true to the Keating sisters’ aesthetic sensibilities and conservation principles. The garden has its striking seasons: carpets of wild snowdrops along the woodland walks in winter, a magnificently flowering Magnolia mollicomata in spring, the early summer azaleas, the September cascades of crimson magnolia fruits and fuchsias. So perhaps the final words should be left to Clough Williams-Ellis. In a letter that now hangs framed in the hall, he writes to the sisters: “In these serene spring days your little kingdom must be heavenly indeed.”

Related: Arch Wizard of Wales: Clough Williams-Ellis Bright Fields on Llyn Warrior Wind-Singer of Llyn Post inspired by Sue Llewellyn’s A Word A Week: Delicate

Uluru on top of the world: one view, several perspectives

“Then the earth itself rose up to mourn the bloodshed—this rising up in grief is Uluru.”

Norbert C Brockman Encyclopedia of Sacred Places

*

This striking eruption of earthly sorrow is only one of the stories that the Anangu people of Australia’s Northern Territory tell about the origin of Uluru (also known as Ayers Rock). Uluru is a sacred place in their tribal land. It is now part of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, which since 1985 has been jointly managed by the Australian Government and the Anangu people. In Brockman’s version of the origin story he says that back in the time of ancestral spirits, two tribes were invited to a feast. But on the way, the guests became captivated by a group of Sleepy Lizard Women and lingered at a waterhole where Uluru now stands. The party hosts took umbrage at their guests’ nonappearance and, feeling insulted, sang evil into the mud they were moulding until it sprang to life as the dingo. Next, a terrible battle broke out and all the tribal leaders were killed. The spilling of their blood caused Uluru to rise up.

Geologists will of course give another explanation. They will say that Uluru is an inselberg, literally an island mountain, a sandstone dome that is the sole remnant after the slow erosion of a mountain range. Tourist guides will tell you that it is Australia’s most famous natural landmark, that it rises over 300 metres above the flat desert scrub, that the tough trek to the top is 1.6 km, and the walk around the base over 9 kilometres.

As I write these facts and figures, I feel myself becoming irritated. Surely they are not the point. I begin to see a little of why the Anangu people do not want people scrabbling all over the place. Come there, by all means, they say. But do not climb. Watch and listen. This is the place where several songlines intersect, and where many sacred ceremonies are performed. It is filled with great meaning and resonance.

Genetic studies have shown that Australia’s indigenous people arrived in that land some 50,000 years ago. In all that vast expanse of time, and until the arrival of Europeans, their cultural view was presumably uninterrupted. They lived a hunter-gathering life well fitted to a demanding environment. There were people living around Uluru 10,000 years ago. What to European newcomers appeared utterly undeveloped and primitive, was rich in metaphor and codes of conduct. And if I have rightly understood what the Anangu people say (see the links below), then physical reality, metaphor, and time itself are meshed as one. Past, present and future are all part of the becoming that began with the first ancestral spirits.

In the beginning, then, the earth was flat and featureless. Next came the spirit ancestors who took the forms of people and animals. In their wanderings across the surface of the world, they instigated acts of both creation and destruction. These brought into being the physical landscapes we see today. They are journeys of becoming, iwara or songlines, and through them was engendered the law, tjukurpa (chook-orr-pa). These are ethical pathways, ways of being and doing that honour the interconnectedness of all things; the relationships between plants, animals, humans and the land itself. The law is remembered and passed on by elders to the rightful inheritors through song, art, stories and ceremonies.

One can see, then, why the Anangu people might feel that the word ‘dreamtime’ does not do justice to the meaning of tjukurpa (law). To the European mind the term suggests something fey and otherworldly. Yet in the physical sense Anangu law is absolutely worldly; it is about showing responsibility towards the land and all living things; honouring existence. This, I would suggest, is the kind of moral geography that we ‘Rich-Worlders’ could do well to acquire—and PDQ? Our trail of destruction across the planet speaks for itself. Our presumption of being ‘on top’ in the civilization stakes is more than a little flawed. We forgot a few hundred years ago to leave only our footprints.

For more about Anangu culture go HERE and HERE and HERE

copyright 2014 Tish Farrell

Looking inside ‘The House of Belonging’: remembering artist Sheilagh Jevons

The following is the account of a conversation I had with Sheilagh in 2014, a year before her death. She is sadly missed.

*

I thought it was time I welcomed good friend and artist, Sheilagh Jevons, to this blog. She lives a few miles from me along Wenlock Edge, in the little village of Easthope. There, and in her studio not far away, she creates arresting work that explores the sense of belonging that people have with landscape. From time to time she and I have involving conversations about the creative process – the stumbling blocks, the sources of inspiration, the way we work (or in my case, don’t work).

A few weeks ago she came round for coffee. I wanted to ask her about a painting I had seen in her studio. I had thought it striking and mysterious, and wanted to know what she meant by it. Besides which, it is hard to resist the opportunity to grill an artist when you have one captured inside your house.

The header image is a small detail from a work called The House of Belonging. This figure has appeared in Sheilagh’s other works and represents women artists. Some of their names are written on the smock, artists perhaps not well known to the general public. Here she pays homage to their work, but also alludes to the fact that, overall, very little work by women artists is to be found in museums. The writing of names and of repeated key-words and equations is characteristic of many of Sheilagh’s pieces. It was one of the things I was going to ask her about. But first, the painting.

It is a large canvas, some 4 feet (120cm) square. The next photo gives a better sense of scale. Here it is hanging in Sheilagh’s studio:

I asked Sheilagh how the work began. She told me that some years ago the idea of belonging had become very important to her. As she says on her website:

Our ‘sense of belonging’ ripples out from our homes to our village, street, town, county, region and country and help to shape our identity…

Key, then, to her work is a sense of connection to land and how that relationship defines us. This in turn has physical expression in community repositories, the places where we keep artefacts, our history, the knowledge of ancestors – all the familiar things we recognise and which tell us something of who we are. In other words, the museum, or as Sheilagh describes it: the house of belonging. The script running down the left-hand margin of the painting in fact repeats over and over the words ‘the museum’, ‘the house of belonging’. The repetition reflects the strong political stance of Sheilagh’s work.

To me this is ‘the writing on the wall’, a statement of collective ownership; The House of Belonging staking a claim. Its contents are manifestations of how humans have interacted with their landscape and the place they call home. Sheilagh also says that adding text creates a certain texture; that the sense of a hand moving across the work creates a connection with her, its maker. The wheeled blue structure, then, is the House of Belonging. The words written inside say ‘everybody’s knowledge’. This is written twice so there can be no mistake. It feels like something to stand up for, a rallying call.

It is also important, Sheilagh says, that the House can move across the landscape to where the people are, rather than the other way round; this makes it more egalitarian. Inside the House are images and artefacts, symbols of creativity. Some of them are stereotypical of ‘heritage’ and therefore instantly recognisable. For instance, the chess pieces (centre left in the painting) are derived from the Scottish Isle of Lewis Chess Set in the British Museum. The set dates from AD 1150-1200 and suggests Norse influence or origins.

Sheilagh copied and simplified the images from a sales catalogue that specialises in heritage reproductions. The placing of the queen in the central position is also significant. She says she feels bound to redress an imbalance: the fact that in most of our media women only occupy centre stage when they are being commodified in some way. And then there is the mathematical equation painted in red beneath the red tree, centre right of the painting.  The presence of equations in Sheilagh’s works adds a further layer meaning for her, and although she doesn’t think it necessary to explain them, she is always very pleased when people recognise them. This particular one refers to mathematical research by American academics in the 1920s called The Geometry of Paths. The appearance of equations in Sheilagh’s paintings also has more personal origins. She tells me she started to include them some years ago – after she had been helping her daughter revise for her Maths and Physics A’ level exams. It is another connection. There are many more signifiers in the work: motifs that have links and resonance with Sheilagh’s other works. The red tree above the equation is a symbol of timelessness, indicating ‘forever’ in human terms.

The presence of equations in Sheilagh’s works adds a further layer meaning for her, and although she doesn’t think it necessary to explain them, she is always very pleased when people recognise them. This particular one refers to mathematical research by American academics in the 1920s called The Geometry of Paths. The appearance of equations in Sheilagh’s paintings also has more personal origins. She tells me she started to include them some years ago – after she had been helping her daughter revise for her Maths and Physics A’ level exams. It is another connection. There are many more signifiers in the work: motifs that have links and resonance with Sheilagh’s other works. The red tree above the equation is a symbol of timelessness, indicating ‘forever’ in human terms.  The red arrow in the top right creates a sense of energy and direction; a ‘look what’s here’ sign. There is the sense of a force field, drawing people to the House of Belonging.

The red arrow in the top right creates a sense of energy and direction; a ‘look what’s here’ sign. There is the sense of a force field, drawing people to the House of Belonging.

Finally, we talked about the overall composition. Sheilagh says that she began the work some years ago after she noticed that a small building denoting ‘museum’ often appeared in her landscapes. This time she wanted it to have it as the main subject, and to make it both an enticing and a mysterious place. At this point she also created the friezes at the top and bottom of the picture, these in order to suggest other layers of reality behind the surface painting. The top frieze is the wider, timeless landscape of which the museum is also symbol. The bottom frieze is deliberately ambiguous and suggestive; it invites the viewer to consider what might lie behind.

And having created the work’s essential structure, the painting was then abandoned. It was only some fifteen months later, when Sheilagh, looking for a large canvas to start another work, returned to it. She was fully intending to paint over it, but when she looked at it again she suddenly knew how to proceed and completed the work very swiftly. She says it probably is not quite finished, and suspects that something may still need to be added. In the meantime she has been occupied with a large body of work relating to Scotland.

And having created the work’s essential structure, the painting was then abandoned. It was only some fifteen months later, when Sheilagh, looking for a large canvas to start another work, returned to it. She was fully intending to paint over it, but when she looked at it again she suddenly knew how to proceed and completed the work very swiftly. She says it probably is not quite finished, and suspects that something may still need to be added. In the meantime she has been occupied with a large body of work relating to Scotland.

Notes and reference materials from Sheilagh Jevon’s studio

© 2014 Tish Farrell

Bright Fields on Llyn: windows in time, mind and space and other stories from Cymru

Oh all right, I confess. My take on the WP photo challenge is a little tangential. Also I have combined it with Ailsa’s travel theme ‘illuminated’ and Frizztext’s ‘B’ challenge (links below). But for me, photographs are windows in their own right, focusing the eye, mind and sensibility. The ones in this post seem to reveal a glimpse of something that require my special attention. And while some shots do in fact include actual windows, most are about those tiny ah-ha moments: the event, image, artefact that opened a window in my mind, whether a crack, or a full-blown throw-back-the-shutters moment.

And so it was stormy September, and the holiday-season well and truly over when Nosy Writer and the Team Leader headed to Wales for a few days. G. had a brand new camera to learn. I, as ever, was happy to snap whatever caught my eye.

We stayed in an odd, but well-meant B & B in Llanbedrog, and set off each day to explore North Wales’ Llŷn Peninsula. The weather was deeply discouraging. Wales has much wet weather, and, with it, an oppositely equal lack of indoor places to visit, especially out of season. The first day it rained so hard there was no choice but to head for the nearest large town in hopes of finding something to do under cover. We drove up the coast to Caernarfon,and once there sat in a car park for an hour while the rain teemed down on the windscreen. Finally, it eased off enough to venture out. By then, the ludicrousness of coming on holiday to sit in a Welsh car park watching supermarket deliveries was beginning to grate.

Swathed in raingear we trailed around an impressive but dreary Caernarfon Castle, the remnant expression of Edward I of England’s systematic oppression of the Welsh people. In 1283 he extended a small Norman motte and bailey castle into a massive fortress – all the better to assert English rule over the Welsh and their princes. In design it is said to recall the walls of Constantinople, seat of Roman imperial power, thus invoking memories of more ancient times when the Romans also subdued the Welsh. These earlier invaders built the nearby fort of Segontium and, like the castle, it commanded the Menai Straits and the island of Ynys Môn (Anglesey) beyond.

Segontium was built in AD77 by the Roman governor of Britain, Gnaeus Julius Agricola, in preparation for the capture Anglesey (see Island of Old Ghosts). Over a thousand years later the castle was built as one in a circle of mighty fortresses to control the people of North Wales. In 1284 Edward’s heir, later Edward II, was born there, and thus proclaimed the first English Prince of Wales. Though English born and bred, I find this hard to swallow.

And so I think I would have found Caernarfon Castle depressing even in broad sunshine – too much death and domination. The best part of the day was definitely lunch in one of the town’s meandering back-streets. At the bistro Blas they welcomed us in from another downpour, and kindly allowed us to drip on their carpet while feeding us delicious food. Not only that, it was so soothingly lavender, both inside and out.

It was the next day, with the rain abating and the sea roiling over the Cricieth breakwater (beneath another Edward I castle) that we spotted the bright field in the first photo. G. thought it was a good opportunity to start getting to grips with his Fujicamera. I snapped the sea.

But seeing that bright field, so astonishingly luminous against the grey sky, reminded me of the poem of the same name, written by the great Welsh poet-priest R.S.Thomas. This craggy, slab of a man was as redoubtable as one of Edward Longshanks’ castles.

In fact he might have been hewn from the bed-rock of his native Wales. And like all such formations he had his fissures, faults and flaws. Many thought him morose, cantankerous, and rife with ambiguity and contradiction. For one thing, he abhorred the Anglicisation of Wales, yet he wrote in English despite being a Welsh speaker. In 1996 he was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature, but lost out to Seamus Heaney.

As a priest he was kindly and sympathetic to the hardships of his parishioners, although this would not stop him from hectoring them from the pulpit, urging them to foreswear any yearning for consumer durables such as refrigerators and washing machines. He could also be judgemental and, as a fierce Welsh Nationalist and political activist, withering about the failure of the Welsh to resist being swamped by Englishness.

Thomas’s poetry, then, can be both trenchant and transcendent. While I do not subscribe to his religion, I honour the spirit of his words. His poems are among those I love most. Here it is then:

The Bright Field

*

I have seen the sun break through

to illuminate a small field

for a while, and gone my way

and forgotten it. But that was the pearl

of great price, the one field that had

the treasure in it. I realize now

that I must give all that I have

to possess it. Life is not hurrying

*

on to a receding future, nor hankering after

an imagined past. It is the turning

aside like Moses to the miracle

of the lit bush, to a brightness

that seemed as transitory as your youth

once, but it is the eternity that awaits you.

R.S. Thomas

*

On our final day it was with R.S. Thomas in mind, and with a little sun at last, we drove down the narrow lanes of the Llŷn Peninsula to Aberdaron where the poet served as a parish priest between 1967-78.

The ancient church of St. Hywyn’s stands right beside the sea. Since the Middle Ages, pilgrims have come there on their way to Bardsey Island, Ynis Enlli, Island of 20,000 Saints. Inside the church are two ancient grave stones belonging to Christian priests of the late 5th/early 6th century. There is also a welcome there: a bookshop full of R.S. Thomas’s poetry books; even a poem to take away. There are also piles of sea pebbles, shells for contemplating your journey, a kneeler that has been stitched with the single word cariad, beloved.

And beside the knave the clear glass window that needs no further embellishment looks out on the sea and islands of Gwylan Fawr and Gwylan Fach. And outside in the sea wind is the graveyard whose stones seem to cluster like a meeting of villagers in their own bright field. And so it is, as we ponder on all these things that our creedless souls, one atheist, one agnostic, know that we too are on a pilgrimage – to seek out the things that truly matter.

R.S. Thomas 1913-2000 Photo: BBC Cymru Wales Walesart

See this brief biography of the poet, made in 1996 when it was thought he would win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Related: Warrior Wind-Singer of Llŷn

© 2014 Tish Farrell

Warrior Wind-Singer of Llyn

It is said that the Iron Man of Mynydd Tir y Cwmwd sings in the wind. I can believe it too: bold laments of long ago battles, a proud Celtic warrior fending off invading Roman governors and power-hungry English kings. Sadly, the cause was lost on both fronts, although at least these days Cymru,* Wales, has its own Welsh Parliament, and Cymraeg, the Welsh language, is nurtured, learned in schools and spoken widely with great pride. And so it should be. It is one of the world’s wonderful languages, the words formed from the rush of sea on rocks, the wind whistling down from the heights of Yr Wyddfa** (Snowdon, Wales’ highest mountain). Under past times of English domination much was done to stamp out the Welsh culture altogether. It is what invaders do – belittle, ban, override heartfelt expressions of a conquered people’s culture.

{*roughly pronounced Kumree and Ur Oithva}

Llyn Coast Path, Mynydd Tir y Cwmwd

*

Recently I have been writing much about preserving and respecting heritage (Valuing the Past…and also Is the Past past saving in The Heritage Journal) but I recognise, too, that nothing stays the same – at least not in the physical world. The Iron Man is a case in point.

The first man standing was a carved ship’s figurehead placed there in 1911 by Cardiff entrepreneur, Solomon Andrews. Andrews had bought the nearby grand house of Plas Glyn-y-Weddw some twenty years earlier and turned it into a public art gallery, the first of its kind in Wales. Today the house is the home of the wonderful Oriel Gallery, run by a trust, and the place where Welsh creativity is celebrated.

Oriel Plas Glyn-y-Weddw from Llyn Coastal Path

*

The ship’s figurehead did not fare so well. In 1980, after it had been set on fire by vandals, local artist, Simon Van de Put replaced it with a figure of an ancient warrior made from recycled sheet steel. As had been envisaged, the warrior , exposed to the sea winds, weathered away until only his boots remained. But in 2002 reinforcements arrived, delivered to the headland by a helicopter and winch.

Today this new Iron Man surveys Cardigan Bay with the kind of stance that says he means to stay. In fact I’m not altogether certain that he might not also be a woman. This warrior, then, is the work of local craftsmen Berwyn Jones and Huw Jones.

To me the rope-like ironwork suggests sinew and muscle. It is thus simultaneously symbolic of both decay and regeneration; a rare act to pull off. The tilt of the head is dignified, but wistful too. I would like to feel I have the courage to stand up behind this guardian.

I am not Welsh of course. As far as I can tell my ancestors were Anglo Saxons and Normans. But if we do not celebrate the best of our culture, our own and other peoples’, then think how much is lost – all those things that make us truly well nourished humans – the poem, the saga, the dance, the metaphor, the hymn, the riddle, the rune, the touching words, the art – all that makes us recollect and care, confers insight and wisdom, gives us heart and good heartedness. For now though I take joy in the knowledge that when the wind blows across Mynydd Tir y Cwmwd (The Headland), even though I am not there to hear it, the iron warrior sings.

The cliff top path to the Iron Warrior

© 2013 Tish Farrell

Related:

For more on Oriel Plas Gwyn-y-Weddw

http://www.oriel.org.uk/en/home/lost-woodland/69-winllan-history

Frizztext’s WWW Challenge

And also: Ailsa’s Travel Theme: Sky

Valuing the past: how much for Old Oswestry Hill Fort?

SIGN HERE: Change.org petition against developing land below the hill fort

*

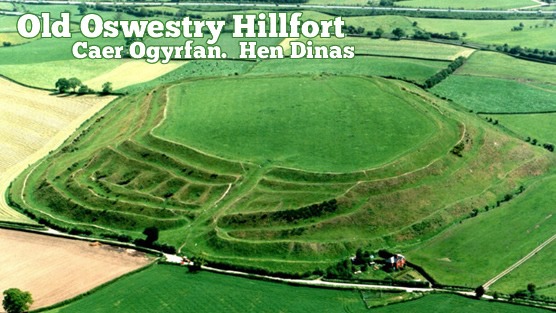

Last Sunday it made the national press – the campaign to stop housing development beside Old Oswestry Hill Fort. You can read The Guardian/Observer article HERE.

Recently I wrote about the Great War poet, Wilfred Owen. Oswestry is his birthplace, and I mentioned that the garden of his former home has planning approval for several upscale houses. All of which leads me to ask, who values heritage the more – the developers trying to cash in on its cachet and so add mega-K to their price tags; or the rest of us, who too often ignore, or take for granted threats to the historic fabric of our towns and countryside? Or who only find out after the event when it’s too late to speak up? Of course, some of us may not care at all: what has the past ever done for me?

In Oswestry, however, they are rallying to the cause of their hill fort, and they have every reason to. It is one of the best preserved examples in Europe, built around 3,000 years ago. On its south side is another important monument – a section of the 40-mile long Wat’s Dyke, probably dating from the early post-Roman period.

Unusually, too, for a hill fort, Old Oswestry is very accessible, being close to the town; it is an important local amenity and landmark and currently in the care of English Heritage. This government funded body does appear to be objecting to at least some of the development plans, but not strongly enough in some people’s opinions. EH will apparently be meeting the developers to discuss matters in December.

Photo from: The Heritage Trust Old Oswestry Hill Fort Under Threat

*

The photo above shows (along the top edge) how close the town is to the fort. The farm complex in the upper left-hand corner, nearest the hill fort, is one of the sites allocated for upmarket housing. Hill Fort Close, Multivallate Avenue anyone?

Below is the view from the other direction, showing the proposed developments. These sites (in pink) are outside the town’s present development boundary. Usually there can be no development outside a development boundary, unless a good case can be made for an exception site for affordable houses. On such sites, houses must remain affordable in perpetuity and are thus normally managed by a housing association or social landlord. So, you may well ask, how come the environs of this hill fort are suddenly under threat, and not from affordable, but from upscale market housing?

*

SAMDev – who’s heard of it?

In Shropshire we have a thing called SAMDev (a nasty-sounding acronym standing for site allocation and management development). Shropshire is one of Britain’s largest counties, mostly rural and agricultural, but with light industry and retail zones on the edges of market towns like Oswestry. SAMDev is a response to National Planning Policy which enshrines the concept of presumption in favour of sustainable development. Spot the weasel word here.

For the last two years Shropshire Council has been ‘consulting’ (theoretically with the communities concerned) on areas of land outside existing development boundaries and identifying locations for housing and employment growth up to 2026. The final plan will be produced by the end of this year and it will be available for public scrutiny before going to an independent assessor.

As part of this process, land owners and developers have been invited to put forward their own development proposals. In other words, SAMDev is rather like a county-wide preliminary planning application. Developers are thus in negotiation with Council planning officers throughout this process. This usually happens anyway with any large development proposal.

This means that when a formal application is finally submitted, it is likely to be passed by the Planning Committee with little argument. The Planning Committee is made up of councillors, people who may have little understanding of planning matters. They rely on the reports presented to them by planning officers. It is the officers who are compiling the SAMDev document.

Although this entire process is available for public scrutiny (all draft plans including individual communities’ Place Plans are on Shropshire Council’s website) I think it’s safe to assume that most people in Shropshire don’t know that SAMDev has been happening. They might have been invited to consult, but somehow they did not understand the invitation, or the implications of not responding. Most people have thus not participated in the consultation process.

The biggest problem is that most normal people do not understand the kind of words that planning people use. I may be cynical, but is this not deliberate? What is clear is that inexplicable quantities of houses have been allocated for big and small towns throughout the county. SAMDev, through its provision of specific sites for specific purposes, is the means by which they will be realised.

*

A case close to home – Much Wenlock

In my small town of Much Wenlock the local landowner has offered up farmland along the southern and western boundaries of the town. This has enabled Shropshire Council’s Core Strategy to make an astonishing allocation of up to 500 new houses in the next 13 years – this in a flood-prone, poorly drained town of 2,700 people, where employment opportunities are poor, and the mediaeval road system is not fit for purpose, either for traffic or for parking. In other words, the town is already full, and its ancient centre cannot be changed, short of flattening it.

Shropshire Council’s Core Strategy states that Much Wenlock needs up to 500 new houses in the next 13 years, increasing the town’s footprint by another 50%. The town sits in a bowl with a river running through it. The development in the foreground is one of the newer ones. Its drains were apparently connected to the old town sewer instead of to the separate system for which it had approval. New developments like this have hidden costs for existing communities. This particular problem has not been rectified six years on from the 2007 flood that damaged up to 90 homes.

*

Development = Sustainable Growth?

The ensuing development fest that will be enabled once SAMDev is passed is seen as a means to stimulate growth. The argument seems to be that communities will die if they do not grow in huge tranches. But this is only a point of view, not an absolute truth. There are other models for sustainability, perhaps more meaningful ones. Besides, every community has its particular characteristics that might suggest other narratives; strategies that enable them to grow without necessarily expanding all over the landscape. Of course it is always easier, and presumably cheaper, to build over new ground than it is to reclaim old buildings and clean up brown field sites within existing settlements. Perhaps this is the reason why Councils do not take over unoccupied homes in towns, even though they have the powers to do so?

*

Trading on the past

In places like Much Wenlock house prices are high because, to quote estate agents and developers, “everyone wants to live here”. People want the best of both worlds, a high-spec modern house with multiple en suites, but in close proximity to gentrified antiquity where people live in homes that be cannot double-glazed because of listed building regulations. The new-home dwellers perceive acquired value by association with the past, and are prepared to pay for it. The kind of properties envisaged for the upscaled farmyard site near Oswestry hill fort will doubtless command a premium for similarly nebulous reasons.

Much Wenlock – view towards the town centre, a ‘60s development on the far hillside.

*

In this way, then, developers trade on something that does not belong to them – the historic setting that is cared for and maintained by other people. Buyers buy into the connection, distracted by the ‘look of the thing’. It’s all rather Emperor’s New Clothes-ish. But then if student debt can now be sold on by banks as a commodity, perhaps heritage detraction can also be a tradable commodity. Communities should exact compensation directly from those developers whose poorly designed housing schemes erode the quality of their environment, whether visually or through added strain on existing infrastructure. (In places like Shropshire effective infrastructure provision does not precede any new housing development; nor, if Much Wenlock is anything to go by, does it follow it.) And I’m not talking here about the modest Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) that developers must pay to communities to build the small but useful things like playgrounds and car parks that councils no longer provide. But something far more substantial.

*

How much for this ancient monument?

So what value do we set on a hill fort? Is it worth twenty million pounds say? Fifty? More? Perhaps august academic institutions around the world might invest in shares in our monuments for their scholarly worth, and provide us with the means to buy off developers, or at least keep them at a respectable and respectful distance.

And I am only half-joking here. It would not be so bad if developers in this country built wonderful, good quality eco-houses in versions to suit everyone’s financial capacity, but mostly they don’t. And in the case of Much Wenlock the cost of large new developments around the town has been high – homes flooded from backed up drains and flash-flood run-off.

*

Standing up for heritage

But where does this leave Old Oswestry and all those who are campaigning against developing the nearby farmland?

Since the Guardian article, support has been gathering from across the country and beyond. You can follow the campaign at Old Oswestry Hill Fort on Facebook. But the problem is that there are only so many arguments you can make against unwanted development, and they have to comply with planning law and the Local Authority’s Core Strategy. They include loss of amenity value, visual impact, access, safety and sustainability.

At present, planning laws and high property prices give all the power to developers. If planning authorities cannot base refusal on the strongest case, then developers will opt for a judicial review to get their way. This costs local authorities a lot of money, and so us a lot of money. Developers’ planning consultants write letters to planning officers threatening legal action. You will find such letters in Council files. This is one reason why authorities cave in without a fight.

The heritage consultant’s impact report on the proposed development near Old Oswestry concentrates on view, THE VIEW of the development from the hill fort, and of the development looking towards the hill fort. The impact is considered to be negligible, but this again is a point of view. Housing developments also come with multiple cars, parking issues, garbage storage areas, satellite dishes, and people living their lives as they might expect to do in their own homes. There is also the future to consider. The Trojan Horse concept is a familiar one in development: approval of one development in due course setting a precedent for the next one alongside.

*

So why protect our past?

One would hope that the land around the hill fort would remain as farmland; that the farm could be sold as a farm. Or it might make a good visitor centre for the hill fort, using existing buildings. In reality there is no need to build anything at all in the vicinity of the hill fort. Better that Shropshire Council use its powers to take control of unoccupied dwellings in the town rather than sanction intrusion into the setting of a historic monument of national importance.

After all, why would anyone think that this was a good idea? These ancient places are resorts, and in all kinds of ways. They feed our imaginations and spirits; for children they grow understanding of other times, and other ways of living: all things that in the end make us wiser human beings. And isn’t this the kind of development we really need? People development? And before we carry on building all over the planet, shouldn’t we stop to consider what we already have, and see if some creative re-purposing cannot shape un-used buildings and derelict sites for our future growth requirements? Or is this approach too much to ask of our elected representatives and public servants?

Copyright 2013 Tish Farrell

SIGN HERE: Change.org petition against developing land below the hill fort

*

Find out about protecting your heritage at Civic Voice and Council for Protection of Rural England and join your local CIVIC SOCIETY

*

Related:

Petition to Shropshire Council at Change.org

The Essential Oswestry Visitor Guide

Old Oswestry Hill Fort on Facebook

The Heritage Journal Oswestry Hill Fort Under Attack

The Heritage Journal Old Oswestry Hill Fort: a campaigner asks – “why aren’t EH entirely on the side of the Public?”

The Heritage Journal Old Oswestry Hill Fort Safe?

The Heritage Journal Oswestry Hillfort “top level talks”: will those who care for it stand firm?

The Heritage Journal Oswestry Hill Fort: is it a forgone bad conclusion?

Undervalued in his home county? Great War Poet Wilfred Owen – a true Shropshire Lad 1893-1918

“It is fitting and sweet to die for one’s country” Horace, Ode III

*

“Dulce et Decorum Est “

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys! — An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime . . .

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under I green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues, —

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

*

Wilfred Owen has been described as the greatest of the Great War poets. He surely was, although in terms of the brutal brevity of his career, it is a dubious honour. The young officer who wrote this poem was killed as he led his raiding party from the Manchester Regiment across the Sambre-Oise Canal on 4th November 1918. At the time, he was twenty five years old and only four of his poems had been published. One week later the war ended. His mother received news of his death in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, just as bells of the county town’s churches were ringing out in joyous celebration of peace. It is hard to imagine the pain of that moment.

Owen, though, believed it was the duty of a poet to tell the truth, to show how it was for the men – this “Pity of War”. He did not have to return to the front after being treated for shell shock in Craiglockhart Military Hospital in 1917. But it was while he was receiving treatment here that he met fellow inmate, Siegfried Sassoon, who became his mentor, and encouraged the young poet to write of the cruel realities of war.

In August 1918 Owen chose to return to the front. In the following October he won the Military Cross for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty in the attack on the Fonsomme Line. And of course he did tell the truth, and in stark, excoriating detail.

*

Wilfred Owen was born and spent his early childhood in Oswestry, Shropshire on the Welsh border, in a gracious villa, Plas Wilmot, owned by his maternal grandfather, Edward Shaw. He was the eldest of four children. His father, Tom Owen, was a railway official, a job that took the family for a time to Birkenhead on the Wirral in Cheshire.

Plas Wilmot, Owen’s birthplace. Photo: Oswestry Family and Local History Group

*

In 1906 the Owens returned to Shropshire, this time to the county town of Shrewsbury where Wilfred attended Shrewsbury Technical School, now the Wakeman School. His last years of education were spent as a pupil-teacher as he struggled to study and win a scholarship to university. In this he failed, and although he won a place at Reading University his parents could not afford to send him. Instead, between 1913 and 1915 when he enlisted, he was went to work as a teacher in France.

The Square in Shrewsbury c 1909

*

The house of his birth is privately owned, and it was only last year, after lobbying by civic groups and historians that it was also given a grade 2 listing by English Heritage; this amid fears of development on the site. In August this year the surrounding gardens were put up for sale with outlined planning permission for the building of seven detached houses on three sides of Owen’s former home. Many have urged that the house and its gardens should be left intact, hoping that one day there might be a museum here. For it is a sad fact that while Wilfred Owen is known of in Shropshire, he is given only scant commemoration.

Yet Wilfred Owen’s words speak to the whole world, for all humanity, a fact recognised at least in France where in the village of Ors, where Owen died, they have commissioned Turner prize nominee, Simon Patterson, to transform La Maison Forestiere (The Forester’s House) into a wonderful place of contemplation and commemoration of Owen’s work. More than this, it is a place to acknowledge the futility of war. It was in this house on 31st October 1918 that Wilfred Owen wrote the last letter to his mother. A few days later he was dead, joining the millions of others lost in the vicious cull of youthful talent and potential. Those of us who come after can only wonder if the full cost of this loss has even now been fully reckoned.

You can see more about La Maison Forestiere in the links below, and a brief biography in the short video at the end.

La Maison Forestiere. Photo: Hektor Creative Commons

© 2013 Tish Farrell

Related:

- The Wilfred Owen Association official site

- Simon Patterson: La Maison Forestière. Dedicated to the British poet Wilfred Owen, 2011, AAJ Press

- Maison forestière d’Ors – Tourisme en Cambrésis

- Regeneration Trilogy by Pat Barker

- Regeneration/Behind the Lines film (1997)

- NO GLORY IN WAR 1914-18 CAMPAIGN

- #shropshirehour

- #nogloryinwar

Island of Old Ghosts

There are ancient, bloody-minded spirits here on Ynys Môn, the island where the Celtic druids made their last stand during the Roman conquest of Britain. This place, otherwise known by its Viking name of Anglesey, lies just off the coast of Wales, the narrow Menai Straits between. One Christmas morning we came here to Penmon on the island’s north-east tip. The light was very strange that day, darkness already gathering at noon. Then across the Straits, above the mainland, the sun bore down like a searchlight.

Penmon is the site of an early Christian monastery, founded in the 6th century by St Seiriol, but the roots of Ynys Môn’s sacred, and now mysterious practices, are far older than this. Across the island there are Neolithic and Bronze Age chambered tombs, and then there is the spectacular Celtic Iron Age hoard from Llyn Cerrig Bach, a seemingly sacrificial lake offering of weapons, chariots, slave chains, and highly crafted regalia. The Romans claimed that in their groves the druid priests made human sacrifices, but little is known of these people beyond the gory account in the Annals of Tacitus. What is known is that the Romans conducted a ruthless campaign against the Celtic clans of Wales. Anglesey, with its powerful druid priests, was the last bastion of British resistance. Here is how Tacitus describes the Menai Straits battle of nearly 2,000 years ago. Suetonius Paulinus, Governor of Britain, was in command.

He therefore prepared to attack the island of Mona which had a powerful population and was a refuge for fugitives. He built flat-bottomed vessels to cope with the shallows, and uncertain depths of the sea. Thus the infantry crossed, while the cavalry followed by fording, or, where the water was deep, swam by the side of their horses.

“On the shore stood the opposing army with its dense array of armed warriors, while between the ranks dashed women, in black attire like the Furies, with hair dishevelled, waving brands. All around, the Druids, lifting up their hands to heaven, and pouring forth dreadful imprecations, scared our soldiers by the unfamiliar sight, so that, as if their limbs were paralysed, they stood motionless, and exposed to wounds. Then urged by their general’s appeals and mutual encouragements not to quail before a troop of frenzied women, they bore the standards onwards, smote down all resistance, and wrapped the foe in the flames of his own brands. A force was next set over the conquered, and their groves, devoted to inhuman superstitions, were destroyed. They deemed it indeed a duty to cover their altars with the blood of captives and to consult their deities through human entrails.

Annals of Tacitus translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb 1884. XIV chapters 29-30. You can read the original work by following the link.

*

For more about Anglesey

In Much Wenlock An Inspector Calls

Much Wenlock, the place where I live, is a small town with a big history. You could say it owes its existence to the discovery of some holy bones. And no, this is not the reason for the inspector’s visit. I’ll get to him in a moment. (In fact his arrival in town relates to the making of some new history). But about those bones…

First of all, they are very, very old. In life they belonged to a Saxon princess, whom we know locally as Milburga, though she comes in other spellings. She was daughter of the Mercian King, Merewalh, who held sway over much of the English Midlands during the 7th century. These were turbulent times – the spread of Christianity going hand in hand with securing territory. To this end, Merewalh was a man with a plan. Instead of arranging dynastic marriages for his three daughters, he established them as rulers of new religious houses across his kingdom. Even his own queen, a Kentish princess, in later life returned to faraway Kent to become Abbess of Minster. In this way Merewalh consolidated spiritual and political prestige, commanding both bodies and souls.

In preparation for the religious life, Milburga was sent for her education to the double monastery of Chelles in Paris. According to the historian, and her contemporary Saint Bede, this was common practice for English girls. Sometime towards the end of the 7th century Milburga then took charge of an abbey in Much Wenlock. This was also a dual monastery i.e. for both men and women, and each sex had their own church. It was also the most important religious house in the region. There she presided for the next thirty years, ministering to the people of her extensive domain lands. Many legends grew up: that she had the power of healing the blind and of creating springs of water. After her death in 725 AD there were more and more stories about her miracles, and so in due course she became Saint Milburga.

Fast forward to the Norman Conquest of Britain (1066), and now we have brow-beating Norman earls establishing their power bases across the land. Their plan was to use ‘big architecture’ to dominate the natives: castles, fortified manors, churches and monasteries – the bigger the better. In Much Wenlock, Earl Roger de Montgomery built a Benedictine priory on the site of Milburga’s abbey. It was affiliated to the monastery of Cluny in France, and so French monks came over to live in it. The building was an impressive enterprise too. Today, the picturesque ruins in the heart of the town do little to indicate the vast scale of the original.

Wenlock Priory and the ruins of 12th century Benedictine monastery that was built on the site of Milburga’s Saxon abbey. In its day, this was one of the biggest and most prestigious religious houses in Europe. Photo: Creative Commons, Chris Gunns

But building big is not everything. The Normans faced a problem that every interloper faces: how to give their occupation legitimacy. Milburga was a much-loved saint and a Saxon saint to boot. It was essential to confirm possession, not only of her extensive lands (which was quickly achieved), but also of her remains.

The last proved less easy and, it may well be imagined, then, that when the French monks arrived in Wenlock and found the silver shrine of Milburga empty but for “some rags and ashes”, there was much consternation. Where were the saintly bones?

Bishop Odo unfolds the mystery in an account written after he visited the Priory in 1190. It appears that the nuns’ church of Milburga’s abbey (now our town church, Holy Trinity, above) still survived in Norman times, but lay in ruins. The monks decided on some restoration, and it was during work on the altar that a monastic servant found an ancient Saxon document. The monks, being French, could not read it and so a reliable translator had to be found forthwith. Thus was discovered the testimony of a priest called Alstan who said that Milburga had been buried near the altar in the nuns’church.

Of course by now nearly four centuries had passed since her death, but news of the document reached Anselm, Bishop of Canterbury and he gave the monks permission to excavate. But before this could happen, two boys playing by the dilapidated altar, caused the floor in front to collapse, which in turn led to the more rapid discovery of Milburga’s remains. This was in 1101 AD, and we know they were her bones because they were “beautiful and luminous” and accompanied by the requisite saintly fragrance deemed to be given off by such relics.

The discovery gave Much Wenlock instant pilgrim-appeal, and the monastic publicity machinery rolled. The Prior commissioned the leading writer on saints of the day, Goscelin, to write about the life of Saint Milburga and so firmly establish the cult of miracles that surrounded her. From that time pilgrims flocked to Wenlock, and the town grew to cater for them. Some of the surviving public houses have their beginnings in the Middle Ages. The Priory itself was wealthy in land and employed a large workforce who were engaged in agriculture and early industrial development including coal mining and iron working. Artisans and merchants were attracted to the area. Trades and services developed to cater for the pilgrims and the Priory. And over all this human business presided the Prior, delivering both spiritual and temporal edicts. It was not until 1468 that the town was handed over to a secular authority.

And so here we have the little market town of Much Wenlock, continuously occupied for a thousand years and presently home of 2,700 souls. It sits below the long limestone ridge of Wenlock Edge whose geology is of international renown. After the monastery was dissolved by Henry VIII in 1540, the town continued to thrive as entrepreneurs moved in to develop the industrial potential of former monastic holdings. The cloth trade and tanning became important. Agriculture and quarrying continued as mainstays since Much Wenlock’s limestone was not only useful for building, but was also burned in kilns to use as fertilizer. Most importantly, as time went on, it became an essential ingredient in the making of cast iron, acting as a flux to remove impurities from the iron.

Indeed, it was at furnaces on Milburga’s former domains at Coalbrookdale, Madeley, and in Broseley that many breakthroughs in the iron industry were made, thus setting off the World’s Industrial Revolution. And the reason these technological innovations took place here was because the locality had all the vital ingredients: limestone, ironstone, fireclay and coal. The tributaries of the Severn could be harnessed for water power, and the river itself provided a trading route down to Bristol. Not only that, generations of monastic workers meant there was a skilled workforce to be utilised when post-Dissolution entrepreneurs moved in to take over monastic mines, iron works and water mills.

We have other claims to fame too. The reason why one of the Olympic mascots was called Wenlock was because it was here in 1850 the town’s physician, Dr William Penny Brookes began the first modern Olympian games. For the next few decades people flocked to Wenlock in thousands to see them. Brookes passed his ideas on to Baron de Coubertin who often visited the town, and so began the International Olympic Committee. The Wenlock Olympian Games are still held every year and provide a popular competition venue for sportsmen and women from all over the country.

But back to the inspector who was left stranded at the top the page. Two years ago Much Wenlock was one of the seventeen front-runner communities in the country chosen by Government to create a Neighbourhood Plan. Since then, cohorts of Wenlock and other volunteers have worked with the community to produce a plan that sets out the kind of development we want in the parish over the next thirteen years. Last week the inspector, the man assessing the plan, came to the Priory Hall, the town’s community centre, to conduct a public hearing.

For reasons that may become apparent by looking at the next photos, large scale development is not a popular proposition in the community. Most of us feel that we have had more than enough. The town sits in a basin. Wenlock Edge and surrounding hills drain through it down a culverted medieval watercourse once known as the Schittebrok. The Victorians did the culverting and there have been so-called remedial schemes since. Some argue these ‘improvements’ have made the problem worse. The town’s footprint has increased some 300% in the last decades with much unsympathetic development that has covered agricultural land with hard surfaces that speed up flooding. Our narrow medieval street system turns roads into rivers during heavy rain. The other serious problem then (apart from traffic congestion) is drains.

In 2007, after 91 homes were flooded due to a combination of flash flooding and poor drainage, the town held a referendum. The vote was 471 to 13 to have no more development until the town’s traffic and drainage problems were resolved. Nothing has been done to improve these matters, our sewage farm is under capacity. The bill for new drainage will cost millions and our private water company is unlikely to fork out. In the meantime the developers and major landowner informed the inspector that they are itching to build 85 houses in the near future, with a suggested total of 250 over all.

At the hearing the inspector gave them ample chance to make their case, and he himself gave no clue as to which side’s view would hold sway. The Neighbourhood Plan wants only small numbers of affordable homes for locals to rent, and a maximum of 25 market homes on a single low density development. But this is not how housing developers work. Much Wenlock’s property prices are high; it is a desirable place to live. They thus want to build up-scale houses with multiple bathrooms. Meanwhile our ageing community would like comfortable smaller places so they can downsize and release their homes to people with families. It is a divergence of objectives that appears to have no sensible resolution.

The British Government’s stance is that building houses is the only way to create ‘sustainable’ communities. So even if the Neighbourhood Plan is passed by the inspector, there is no knowing how far it will protect the town from inappropriate development.

As I said at the start, Much Wenlock is a small town with a big history. But perhaps our story has not yet been well enough told. Perhaps we are not shouting it loud enough. Events that occurred in and around Milburga’s former domain have helped change the world we all live in. A few miles away is the World Heritage Site of the Ironbridge Gorge (site of the world’s first cast iron bridge built in 1779). The iron, porcelain and decorative tile industries that grew up in this area traded their goods across the world. Monastic enterprise underpinned the development of British industry.

Today if you visit Much Wenlock it may strike you as a Rip Van Winkle sort of place. It has a slumbering air, as if dozing under the weight of ancient timbers and stonework. But it can be lively too.There are some excellent shops including two excellent book shops and a gallery. There are small markets during the week, a museum, the church, the Priory, the Olympian trail, good pubs and hotels, many societies to join, a fully equipped leisure and arts centre.

Above: glimpse of the Prior’s house, now a private home. Below: cottages on the Bull Ring

We have much to protect and preserve here, and much to share with those who visit us. And we do want the town to grow and thrive, but on the community’s terms and according to their expressed needs. But looking over the last thousand years, this story does have a common theme. Whether we’re talking of Saxon kings, Norman earls or housing developers, those who have power and land do all the ruling, too frequently asserting their will over the wishes of the general populace. It remains to be seen whether the inspector will pass our plan. He said he would let us know in November. In the meantime, I, like others in the town, watch rainy skies with anxious eyes, if not for ourselves, then for vulnerable neighbours. Fingers crossed for Neighbourhood Planning and that it actually will serve our purpose.

© 2013 Tish Farrell

Related:

https://tishfarrell.wordpress.com/2011/06/27/of-silurian-shores/

https://tishfarrell.wordpress.com/2013/06/04/windows-in-wenlock/

https://tishfarrell.wordpress.com/2012/01/26/of-wolf-farts-windmills-and-the-wenlock-olympics/

twitter: @Wenlock_Plan

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Wenlock-Edge/532033273535604?ref=profile

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Wenlock-Edge/119957538050970

BOOKS:

W F Mumford Wenlock in the Middle Ages 1977 re-published under ISBN 0950561606

Vivien Bellamy A History of Much Wenlock 2001 Shropshire Books ISBN 9780903802796