In the second part of my black & white tour of Much Wenlock (part 1 here), I was further inspired by Marilyn’s Wednesday photo prompt at Serendipity. This week she chose ‘small town summer’. I thought it would be interesting to see if I could capture that sense without using colour.

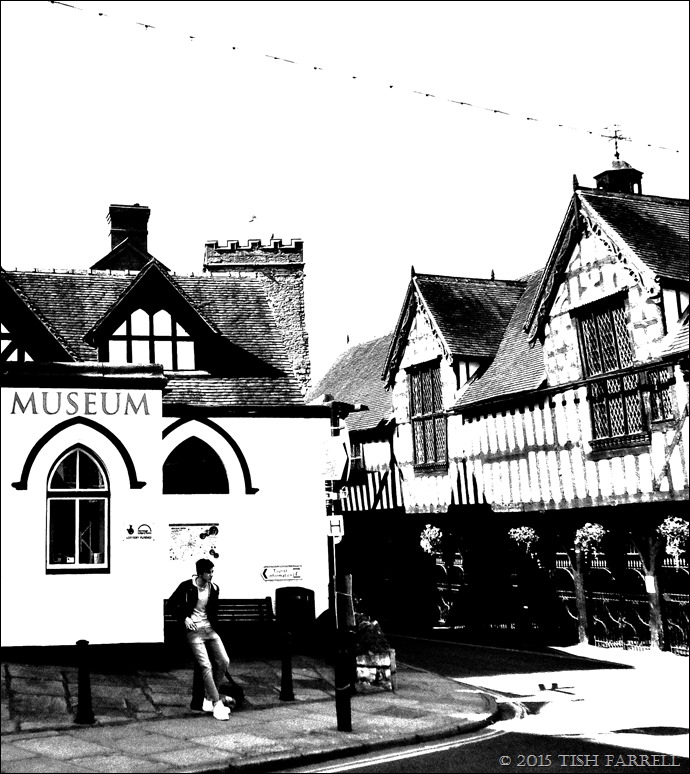

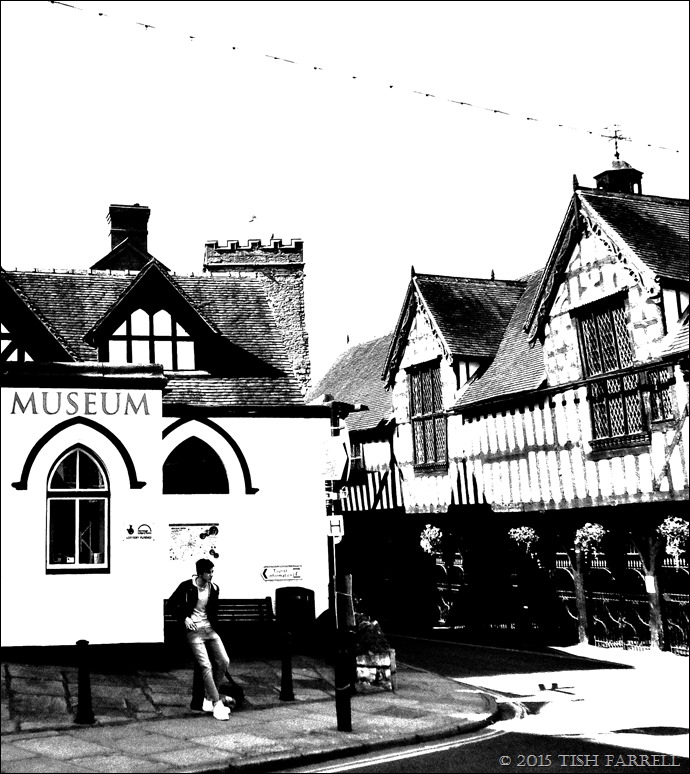

So it is Wednesday, half-day closing. A warm July afternoon. Wenlock is drowsing, although there are some visitors wandering here and there. In the heart of the town, where the High Street meets Barrow Street, a young man is waiting – for his girl? For his best mate? On the right is the sixteenth century Guildhall described in part 1, behind him, the former Victorian Market Hall with its added World War 1 Memorial frontage. This building was also the local cinema in the 1950s. Now it is our museum and tourist information centre, but due to council cuts, it is not open much.

Here, then, is the town centre from the boy’s point of view. There is little of interest for young people. His posture, the high-lit ‘not-much-happening-here’ of the following street scene triggers my own response – that long-ago sense of adolescent ennui: that permanent sinking feeling of alienation.

In the five o’ clock shadows past and present coalesce. It could be oppressive. In the Square the Jubilee Clock is a local landmark. Its several faces used to tell different times, but it has recently been overhauled and given a new electronic movement. It was donated in 1897 by a town worthy, erstwhile emporium owner and august alderman, Thomas Cooke. It celebrates Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee, and would have been in sight of Mr. Cooke’s shop that stood next to the Museum and is currently occupied by the open-all-hours Spar Supermarket.

The buildings around the Square are modern – a pastiche of local architectural idioms. But the open space is pleasing. For years it was occupied by a derelict stone barn. These days it is a gathering point for locals and visitors alike, and a good place to sit and watch the world go by, albeit a rather small and slowly moving world.

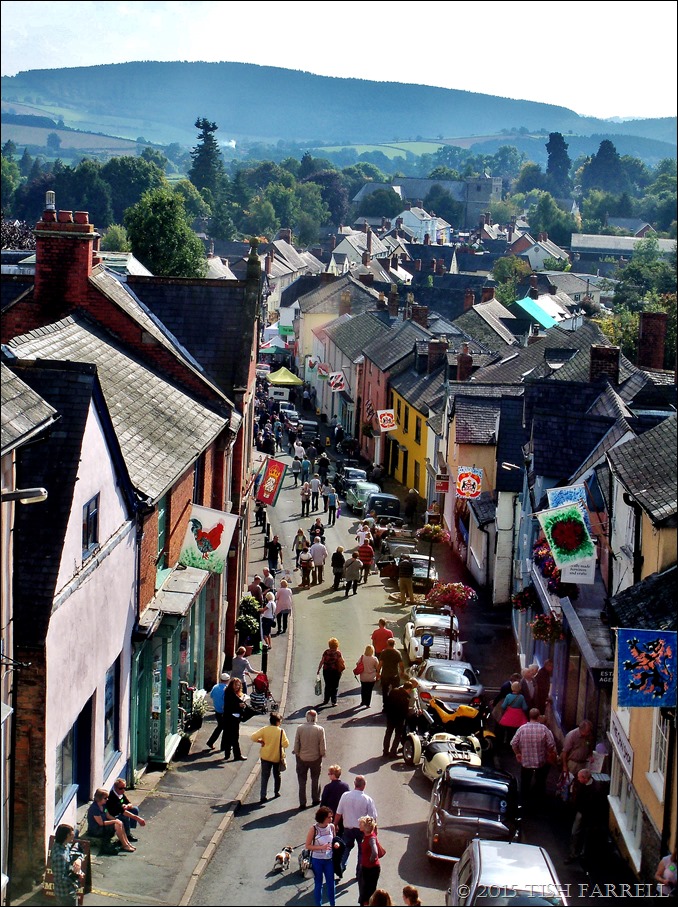

The High Street is difficult to capture. It is narrow, and its east-west alignment means that one side or the other is always in shadow. Then there are the cars in the way, either parking or manoeuvring through. Surprisingly, there is fervent trader resistance to pedestrianizing the street. They think they will lose custom. I think they should at least try it for six months. They might be agreeably surprised at how many more visitors would come to enjoy this little street in peace. It can offer so much hospitality and interest along the way.

For a start we have two ancient inns whose origins go back to monastic times. The George & Dragon is probably everyone’s idea of an unadorned old English pub – all beams and quarry tiled floors.

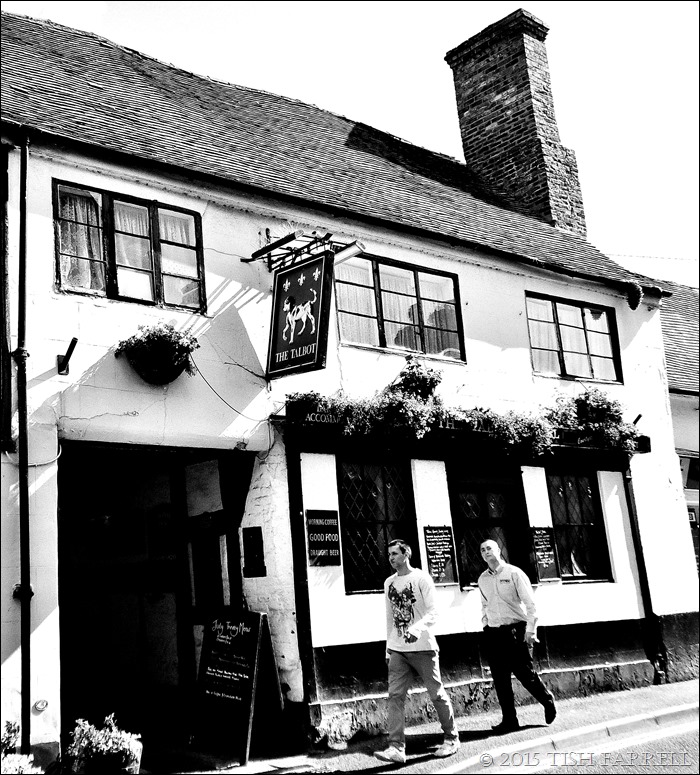

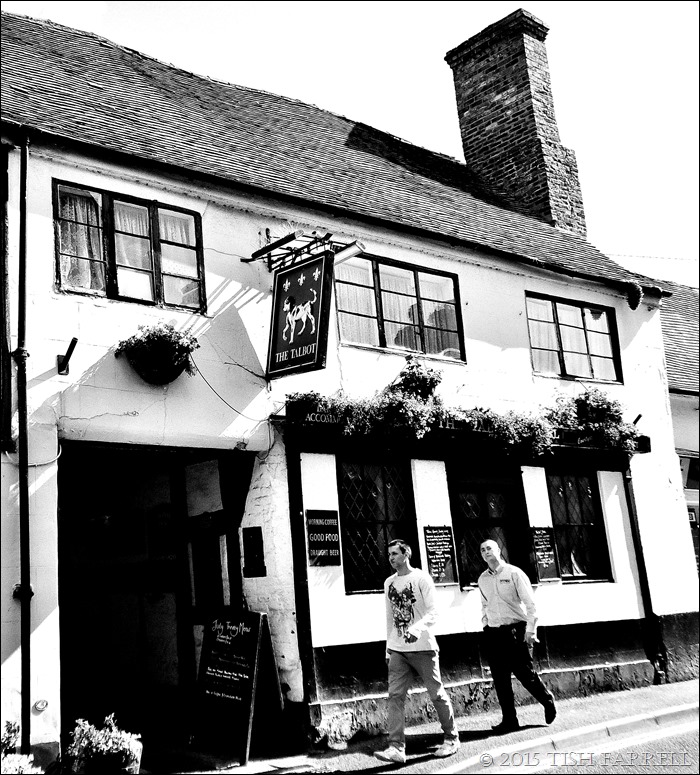

The Talbot on the other hand has a 1970s ‘olde worlde’ interior, though it dates back to 1360, and was thought to be the Almoner’s House, a hostel for pilgrims come to worship at the shrine of St Milburga, and also a centre for alms giving. The white rendered facade hides its timber-framed antiquity, but if you step under the arch you will find a pretty courtyard, where there are also nice B & B rooms in a converted malt house should you want to stay longer.

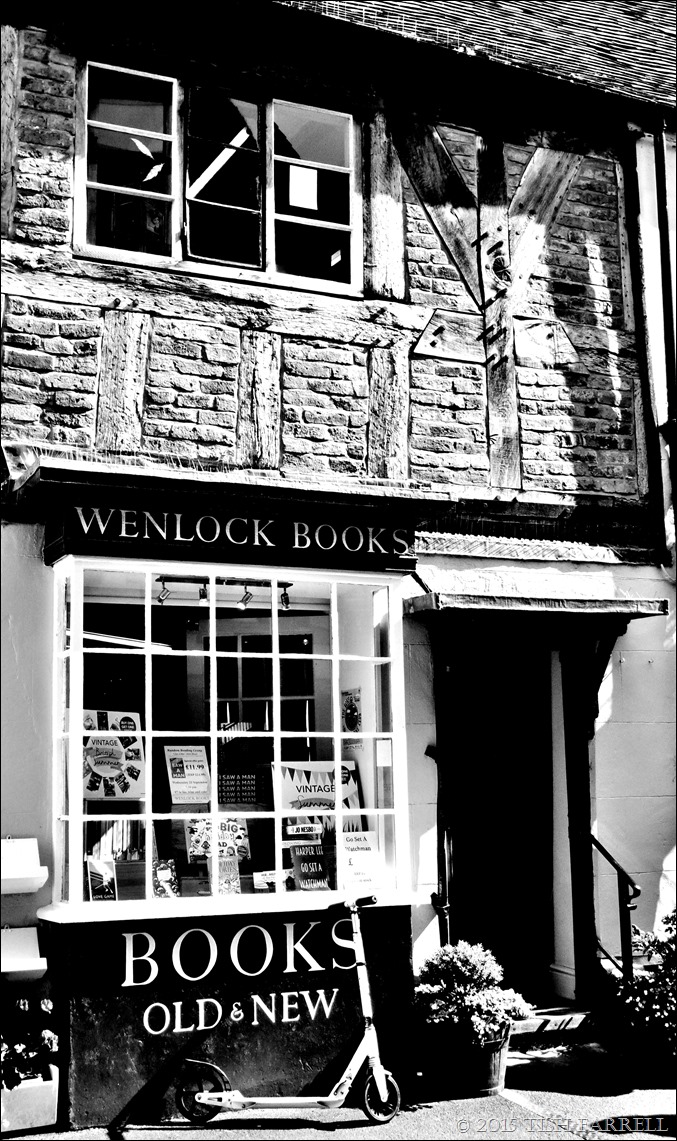

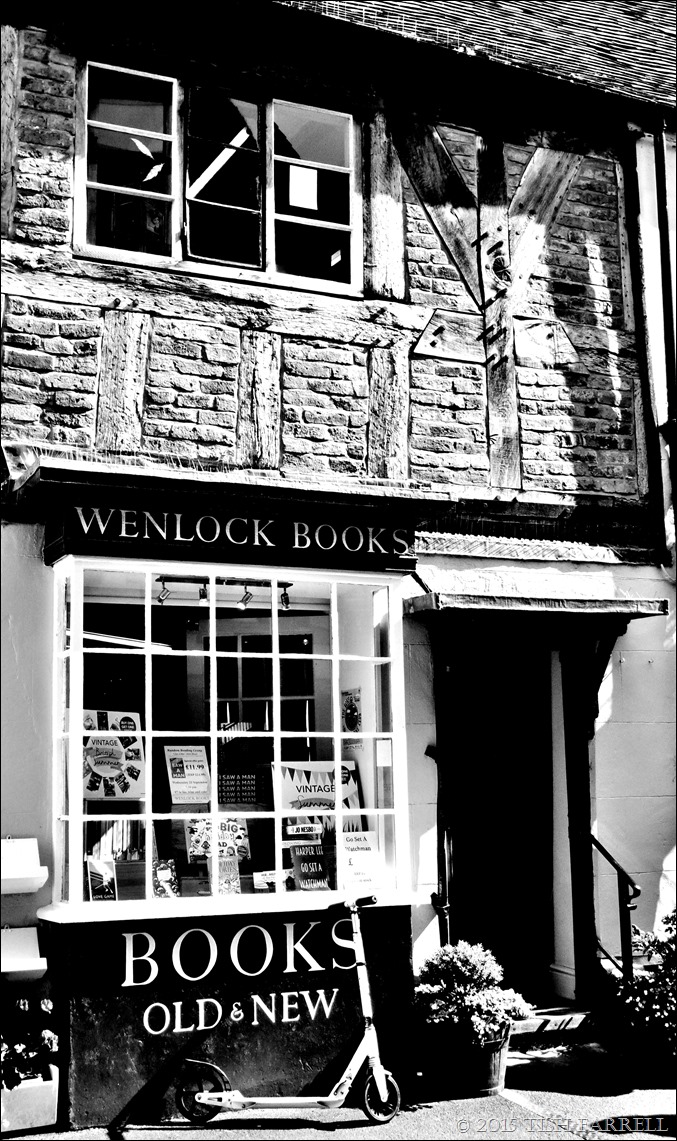

There are also two cafes, one with a deli, an Indian restaurant and two hotels. And amazingly for a small town, we have two bookshops – one dealing in second-hand books, and the other an inspirational survivor among the country’s dwindling number of independent book shops. Its owner, Anna Dreda, not only sells new and old books, but she also hosts reading groups for infants and adults, puts on author talks and book launches, and she is the founder of the Much Wenlock Poetry Festival. Browsers may further find themselves offered a cup of coffee or tea, and invited to pass away the hours in one of the cosy corners upstairs. In short, the shop and its owner are among the town’s treasures, and have won national notice to prove it.

And it is from upstairs in Wenlock Books that you can sneak a good view of the High Street’s mid-section: Mrs P’s newsagents and sweet shop, the estate agents, and Ippikin, a shop that is its own art installation and is our very special haven for knitters and crafters. These next two photos were taken earlier in the day.

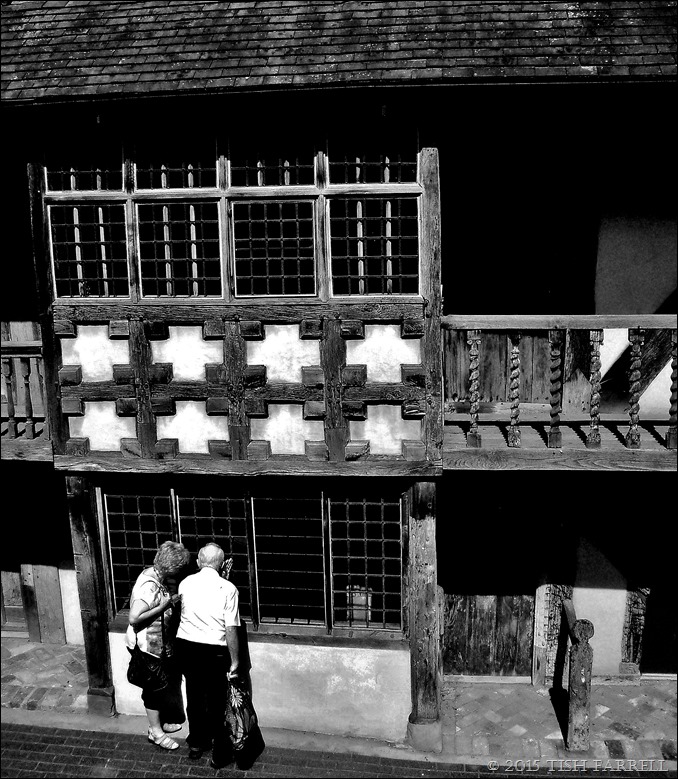

Opposite the book shop is the street’s most impressive historic house, Raynald’s Mansion. Here we have a medieval hall clad first in a flat-fronted building of 1600, and then extended by the addition of three timbered bays in 1680. The property remained in the Raynald family until the late 20th century, and is still a private house. In the nineteenth century it was actually a butcher’s shop, and the rail beside the right hand doorway was an aid to tradesmen lifting heavy loads.

And next is another town treasure, Twenty Twenty Gallery. I missed it out. It is further back down the street towards The George & Dragon, and every month has a new exhibition of contemporary art, ceramics and jewellery for sale. The owner, Mary, likes to feature the work of local artists and makers.

Back again down the street beyond Raynald’s Mansion and The Talbot Inn we have another imposing house, also early 17th century. Up to the 1920s it was the Swan and Falcon Inn. Later it housed our local branch of Barclays Bank until it moved to smaller, less frequently open premises next to the Post Office. The current new owner has development plans for it and its ancient medieval barns out back, but in the meantime our local wildlife rescue charity has it shop there.

And just in case you think all is perfection along our High Street, we do have our eyesore. In 2009 or thereabouts the space next to the old Swan and Falcon was the scene of a general town uprising. A local developer, who had put up an unpopular housing enclave behind the High Street, then erected a house on the street frontage that did not conform to the approved plans. So after considerable agitation, down it had to come, although only after we Wenlockians had frightened the visiting local authority planning committee by our vociferous objecting. It was rather like a similar revolt back in Wenlock’s 1300s, when the serfs, fed up with the domineering Bishop who ruled both Priory and the town, threw down their ploughshares in general protest.

The site itself was once a seventeenth century clay tobacco pipe works, and in more recent years had become overgrown, and thus a well treed wildlife area that helped mitigate the town’s flooding risk. The only problem is that ever since, the space between the Swan and Falcon, and High Street’s terrace of Tudor cruck cottages, has looked like this, one of our less than successful visitor attractions:

Somewhat surprisingly, the original planning permission for the housing development, both on the street, and behind it, had been given without any reference to, or consultation with the local authority’s Conservation Officers. Apparently it was not deemed necessary with a new development, despite the site being in the middle of an ancient town. Anyway, the houses were expensive, cramped inside, and so took a lot of selling, even with offers of free cars. In the end a housing association bought many of them, so at least some families on the local social housing list have benefitted.

By contrast, this row of cruck cottages some 400 years old, and the new development’s nearest neighbours, are solidly built, remarkably spacious inside, and have very pretty gardens behind them. Lacking the paper thin walls of new houses, there is doubtless little noise leakage between the cottages, although they do lack multiple en suite shower rooms that seem to be a feature of all English new-builds these days. Anyone would think water grew on trees, or that our drainage systems were robust enough to cater for all the washing we think we need to do.

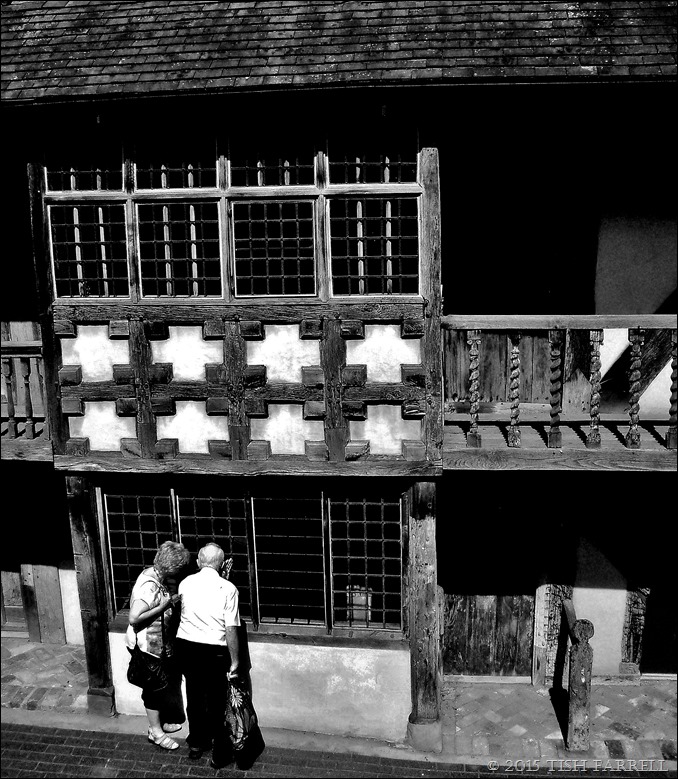

Finally, here is one of the town’s loveliest ancient houses Ashfield Hall. I’ve mentioned its history in an earlier post. It was built by one Richard Ashfield who lived in Wenlock in 1396. It is probably on or near the site of the earlier St. John’s Hospital which was a hostel for poor itinerants.

And there you have it: some of Wenlock’ High Street highlights. It is well worth a visit.

copyright 2015 Tish Farrell