‘The eye that leaves the village sees further’ Maasai wisdom

Photo courtesty of https://www.justgiving.com/MaasaiCricketWarriors/

*

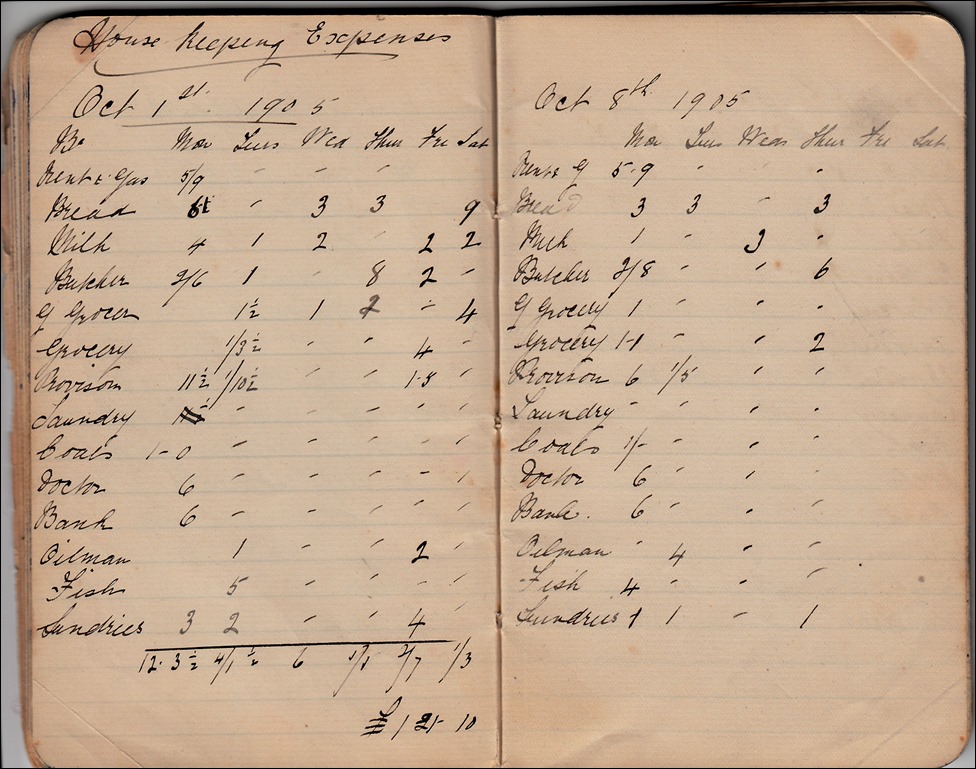

It’s already been shown in Hollywood, but today in London sees the release of Warriors, a documentary by Barney Douglas. From next week there will be star showings across the UK, so if you have a chance to see it, do. You will see a glimpse of real, magnificent, originally-minded Africa, and not only that, 45% of the film’s proceeds will go towards one of the best community causes I can think of – changing attitudes to a rite that these young Maasai men say must go – female genital mutilation, aka female circumcision or FGM.

The stars of the film are a team of cricket playing Maasai warriors. They’ve been playing since 2009, and their ambition was to play at Lords, which they did this summer. They are a fine sight to behold in full morani gear plus bats and pads. And they are killer cricketers. They could even rouse my interest in a sport that usually makes my brain glaze over, despite that lovely sound of leather thwacking willow.

Working as volunteers, these young men have been using their growing popularity to spread the word against FGM and forced early marriages. Their far-flung travels have earned them the right to be heard by the elders back home, and now the young men are saying that they will refuse to marry a girl who has undergone FGM. In a community that has clung to the rite despite the enactment of Kenya’s 2011 Anti-FGM law, this is a powerful stance. It will bring change.

This is what the team captain, Sonyanga ole Ngais had to say at the Warriors Premier:

Thank you for helping us with our inevitable war against FGM because we know that all gender inequalities are related to FGM. Eradicating FGM means that the girl-children shall not be forced to drop out of school in preparation for early marriage and early motherhood. This directly translates that the girls can be educated, gain a bargaining power to choose her own path, when to marry, her own chosen husband and when to get her children. It translates to better health, better economy and better self-esteem. Simply, an FGM free community is a healthy, empowered and wealthy community.

Photo: http://maasaicricketwarriors.co.ke/

You can see the trailer for Warriors HERE

And now to my personal interest in this anti-FGM initiative from within a practicing community.

Back in 2002 I was asked to write an article on FGM for the inaugural issue of Zuri , a US magazine aimed at African American teen girls. Zuri means beautiful in Kiswahili and the magazine’s founder, and editor-in-chief, Donna D King wanted to produce an attractive bi-monthly journal that would raise young women’s aspirations in everything from their appearance to their values, beliefs and career choices. The publication had a strong Christian ethic, and Ms King also wanted to include articles that would deal plainly with issues that might affect young women of colour. (Sadly, the magazine is no longer around.)

At the time of this commission, I had not long returned from Africa where we had been living for eight years. For most of this time we were in Kenya, and throughout the 1990s the topic of female genital mutilation, usually referred to as ‘female circumcision’, along with reports of forced teen marriages, was frequently covered by the national press. In theory, the rite was illegal in all its forms. In practice it did, and clearly still does take place.

In Britain FGM is a criminal offence, and rightly seen as a human right’s violation. Since the summer, all health care officials have been told they must report any suspected cases.

But this is only one side of the problem. We all know that making something illegal does not stop it, otherwise our nations would have no need for police forces, customs officials and judiciaries. By far the most effective measures to end such practices, I would argue, must come from within the communities who practice them. Certainly in Kenya, this kind of community activism has been going on since the 1990s. It is a slow process for all kinds of reasons, which I go into below. But high-profile initiatives like the Maasai Cricket Warriors, and now the Maasai Cricket Ladies – YOU CAN SUPPORT THEM ON FACE BOOK – just make me want to give a loud resounding HURRAH!

Anyway, here’s what I wrote back in 2002 with one or two statistical updates:

The Cruellest Cut?

It is easy to condemn a stranger’s customs, and when it comes to a rite as hazardous as Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), it is not surprising that our first response is BAN IT. In the United States, the UK and many industrialized nations, FGM is illegal, but in several Middle Eastern and many African countries, FGM is both legitimate and common. In a country like Kenya where 12 out of 40 ethnic communities ‘circumcise’* their young women, the debate for or against FGM has been simmering since 1929 when European missionaries first tried to stop the custom.

But despite all the laws and adverse criticism, the rite is not going away.

The World Health Organization estimates that up to 140 million girls and women have undergone one of the three main types of FGM. Plan UK further states that every year across Africa, 3 million more girls will undergo the rite. And so today, as you go to school, cruise the mall, or watch TV, the genitalia of 5,000 girls will be cut off in unsanitary surroundings. The victims may be infants, five year olds or young teens. They may be cut by force or submit willingly. They will suffer it because those who love them most—their mothers, fathers, grandparents—say they must, and because it has always been done.

Then there is the side of this issue that most affects industrialized nations. When people from communities who practice FGM migrate from their homelands, they take the custom with them. For parents settling among strangers whose lives seem far from moral, the belief that FGM is the only way to protect their girls’ virginity is likely to be reinforced. If the rite is illegal in the adopted country, they will simply take their girls on a visit to their homeland.

In criminalizing FGM many nations, including the US, UK, Kenya and Egypt, have acted with the very best of intentions, and with aim of protecting vulnerable girls. FGM has serious health risks: haemorrhage, shock, septicaemia, sterility, abscesses, chronic pelvic and urinary infections, incontinence caused by rupture of urinary and rectal tracts, painful periods, painful sexual relations, keloids (raised spreading scars), long labour, frequent stillbirths, foetal damage, and depression.

Some mutilated girls bleed to death. Others die in childbirth. Very many suffer in silence their entire lives because talk of the rite is taboo. They may not even realize that FGM caused their chronic bad health problems.

So what precisely is female genital mutilation? The World Health Organization lists three main forms:

Type I. Clitoridectomy—removal of all, or part of the clitoris. This type of FGM includes the least damaging form, Sunna, which involves cutting off the prepuce or clitoral hood.

Type II. Excision—removal of the clitoris and part, or all of the labia minora. This can cause massive scar tissue and, later, difficulties in childbirth.

Type III. Infibulation—removal of clitoris, labia minora and labia majora. The raw surfaces of the vulva are then stitched together using thorns and gut. A pencil’s width hole is left for the passing of urine and menstrual blood. After this procedure, the girls’ legs may be bound together for up to 40 days to ensure the cut surfaces heal to make a permanent cover over the vagina.

The pain and trauma of infibulation haunts many women all of their lives. After marriage, the bridegroom cuts the sutures, and then replaces them later. During childbirth, the sutures must also be cut, but after the baby’s birth, the woman will be stitched at once to ensure her husband’s honour. This act of re-stitching causes further scar tissue and makes future childbirth hazardous.

The FGM ‘surgeons’, usually a caste of older women whose livelihood it is, rarely use any form of anaesthesia. They may also use unsterilized tools such as broken glass, scissors and razor blades for a procedure that can last as long as 20 minutes.

These, then, are the facts of FGM, but its cultural justifications are varied and complex, and the reasons for it deep-rooted in tradition. Also, the reasons for Types I and II are very different from the most extreme form, infibulation. The former are usually associated with traditional ceremonies that initiate adolescent girls into womanhood. In most of the African societies that practice FGM, Sunna, the least damaging form, is the one most commonly used to mark the transition to womanhood.

Initiation of this kind is usually associated with the onset of puberty and menstruation. Oral history sources suggest that in pre-colonial times girls did not begin to menstruate until they were at least 17 years old, and thus already old enough for marriage. When FGM took place it was in association with training for adult life. Young women would be secluded in special camps, often for several months. Here they would learn from their female elders everything they needed to know about married life and sex. They would be schooled in how to conduct themselves as good mothers and responsible community members. They would learn clan history and special songs and dances. They would be taught to behave with quiet dignity, and be prepared by their tutors to bear the cutting without showing fear or crying.

In every sense this process represented a graduation. Afterwards, when the girls returned to their community as proven brave young women who could endure extreme adversity, and so were ready to play their part, everyone showered them with gifts and praise, and the whole event was celebrated with general feasting and dancing.

Today, due to school attendance and church membership the valuable training associated with this rite of passage has long gone, but women still send their daughters and granddaughters for “the cut” because they see it as a badge of womanly status. Without it, they think their girls will be outcasts in the community and thought of as unclean, promiscuous, or childish and, therefore, wholly unfit for marriage. Traditionally, an unmarried woman in many African societies has absolutely no status.

For many poor rural women, then, FGM is seen as the only way they can gain some standing in their community. In such situations the women themselves are the main upholders of the rite. They are not prepared to lose the sense of status they believe it confers on them, even if this means crossing husbands’ and elders’ wishes. They will shrug off the dangers, saying the benefits far outweigh them. This situation was dramatically exposed in Ousmane Sembene’s award-winning Senegalese film Moolaadé (2004).

The Kenya situation also shows up the flaws in simply outlawing the practice. In 1982 when President Daniel arap Moi announced his plan to ban FGM, those communities that practiced the rite rushed to have their daughters cut before the law could be passed. In fact Kenya’s Anti-FGM law was not enacted until 2011, and even now it is difficult to enforce among remote communities. There has also been a trend to ‘circumcise’ girls at ever younger ages. But without the appropriate accompanying sex education, which neither school nor church tends to provide, the upshot has been an epidemic of school-girl pregnancies, and the inevitable abandonment of education.

Unexpectedly, too, sending girls to school may also help to keep FGM alive. Circumcised girls are said to apply fierce peer pressure by ostracizing uncut girls. Furthermore, since rural girls must often go to boarding school to receive an education, their parents believe that FGM will stop their daughters from misbehaving while they are away from home. They also think it will protect them from HIV infection.

All the social changes, coupled with the fear of AIDS, have often served to entrench the practice of FGM types I and II. Yet at the same time, the rite has lost much of its original meaning. Instead of being an important rite of passage that admits a girl to a higher social status, it now largely serves to control girls’ sexual behaviour in much the same way as type III infibulation does.

This, the most extensive form of FGM is practiced in deeply conservative societies, where virginity and wifely faithfulness are upheld as matters of high family honour. In Somalia, for instance, families commonly infibulate their girls by force by age five as former Somali model, Waris Dirie’s moving book Desert Thorn painfully reveals.

Infibulation is also practiced in Egypt, Sudan, and parts of West Africa, where is often associated with the Muslim faith, despite the fact that FGM long pre-dates Islam. This form, then, presents anti-FGM campaigners with their biggest challenge; the communities who practice it are fiercely independent and do not care to be told that their customs are wrong.

So how, then, can FGM be stopped? Is criminalizing it the answer? Is legislation a viable answer when so many women choose it for their daughters and granddaughters?

In Kenya many community activists have realized that banning the rite can simply drive the practice underground. Since the late 1990s they have been devising more proactive approaches, in particular helping communities to create new ceremonies—ones that confer status but without the cut. One example is called “Ntanira na Mugambo,” translated as “Circumcision Through Words.” It has been promoted by Kenya’s national women’s group, Maendeleo ya Wanawake, and involves a new one-week ceremony.

Each ceremony is tailored to meet different cultural needs but, for all girls who attend, the objective is to teach them about personal health and hygiene, their future roles as parents, wives and community members, the importance of staying in school, and how to handle peer-pressure. In communities where the male view predominates, the building of self-esteem is also key. At the end of the week the young women graduates are given certificates and gifts by their community and generally feted in the manner of traditional ceremonies.

Little by little this new rite is gaining acceptance. But it is no quick-fix solution. The entire community must embrace the new rite. In particular elders, husbands and young men must be persuaded. In a bid to gain everyone’s support, campaigners organize preliminary discussion groups in churches and in youth groups. They encourage men, in particular, to carry the anti-FGM message to others.

Campaigners have also found that focusing on FGM’s health problems is the surest means of persuasion, whereas condemning cultural beliefs or sexual attitudes is very counter-productive. Finally, campaigners ask young men supporters of the new rite to swear an oath that their future wife need not be circumcised.

Because the rite does not exert a blunt prohibition on female genital mutilation being practiced in Kenya, but offers an attractive alternative, it is possible that it may become the most successful strategy towards more widespread elimination throughout the world.

César Chelala, global health consultant The Lancet 1998

These and similar initiatives are now proving powerful tools for change in Kenya and other African countries. They also have the support of international agencies such as the World Health Organization, the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH), and UNICEF.

Even so, no one underestimates the time it will take to eradicate FGM completely. No human being’s beliefs are easily changed, no matter who they are. Most campaigners agree that it will take at least three generations to end the practice. It also seems likely that informed and non-judgmental persuasion from within communities offers the best hope of success.

As onlookers we may justifiably feel horror, anger and disgust, but if we are honest, and think how we ourselves might react to outsiders’ condemnation of our cultural practices, we will see that judgmental pronouncements are more likely to harden attitudes than to change minds for the better.

* female circumcision is a term of convenience often used in practicing communities, but the large scale of mutilation in FGM in no way equates to male circumcision.

copyright 2015 Tish Farrell

Related:

Kenyan girls taken to remote places to undergo FGM in secret The Guardian 2014

You can read a young Kenya woman’s personal account of FGM HERE

#FGM #MaasaiCricketWarriors #MaasaiCricketLadies