SIGN HERE: Change.org petition against developing land below the hill fort

*

Last Sunday it made the national press – the campaign to stop housing development beside Old Oswestry Hill Fort. You can read The Guardian/Observer article HERE.

Recently I wrote about the Great War poet, Wilfred Owen. Oswestry is his birthplace, and I mentioned that the garden of his former home has planning approval for several upscale houses. All of which leads me to ask, who values heritage the more – the developers trying to cash in on its cachet and so add mega-K to their price tags; or the rest of us, who too often ignore, or take for granted threats to the historic fabric of our towns and countryside? Or who only find out after the event when it’s too late to speak up? Of course, some of us may not care at all: what has the past ever done for me?

In Oswestry, however, they are rallying to the cause of their hill fort, and they have every reason to. It is one of the best preserved examples in Europe, built around 3,000 years ago. On its south side is another important monument – a section of the 40-mile long Wat’s Dyke, probably dating from the early post-Roman period.

Unusually, too, for a hill fort, Old Oswestry is very accessible, being close to the town; it is an important local amenity and landmark and currently in the care of English Heritage. This government funded body does appear to be objecting to at least some of the development plans, but not strongly enough in some people’s opinions. EH will apparently be meeting the developers to discuss matters in December.

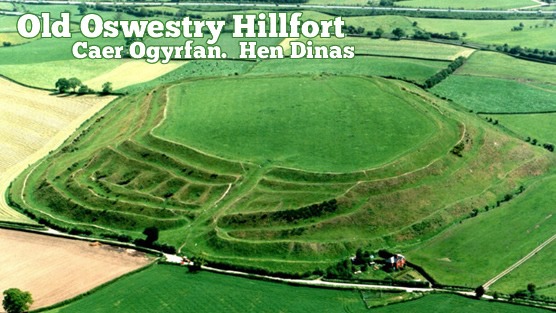

Photo from: The Heritage Trust Old Oswestry Hill Fort Under Threat

*

The photo above shows (along the top edge) how close the town is to the fort. The farm complex in the upper left-hand corner, nearest the hill fort, is one of the sites allocated for upmarket housing. Hill Fort Close, Multivallate Avenue anyone?

Below is the view from the other direction, showing the proposed developments. These sites (in pink) are outside the town’s present development boundary. Usually there can be no development outside a development boundary, unless a good case can be made for an exception site for affordable houses. On such sites, houses must remain affordable in perpetuity and are thus normally managed by a housing association or social landlord. So, you may well ask, how come the environs of this hill fort are suddenly under threat, and not from affordable, but from upscale market housing?

*

SAMDev – who’s heard of it?

In Shropshire we have a thing called SAMDev (a nasty-sounding acronym standing for site allocation and management development). Shropshire is one of Britain’s largest counties, mostly rural and agricultural, but with light industry and retail zones on the edges of market towns like Oswestry. SAMDev is a response to National Planning Policy which enshrines the concept of presumption in favour of sustainable development. Spot the weasel word here.

For the last two years Shropshire Council has been ‘consulting’ (theoretically with the communities concerned) on areas of land outside existing development boundaries and identifying locations for housing and employment growth up to 2026. The final plan will be produced by the end of this year and it will be available for public scrutiny before going to an independent assessor.

As part of this process, land owners and developers have been invited to put forward their own development proposals. In other words, SAMDev is rather like a county-wide preliminary planning application. Developers are thus in negotiation with Council planning officers throughout this process. This usually happens anyway with any large development proposal.

This means that when a formal application is finally submitted, it is likely to be passed by the Planning Committee with little argument. The Planning Committee is made up of councillors, people who may have little understanding of planning matters. They rely on the reports presented to them by planning officers. It is the officers who are compiling the SAMDev document.

Although this entire process is available for public scrutiny (all draft plans including individual communities’ Place Plans are on Shropshire Council’s website) I think it’s safe to assume that most people in Shropshire don’t know that SAMDev has been happening. They might have been invited to consult, but somehow they did not understand the invitation, or the implications of not responding. Most people have thus not participated in the consultation process.

The biggest problem is that most normal people do not understand the kind of words that planning people use. I may be cynical, but is this not deliberate? What is clear is that inexplicable quantities of houses have been allocated for big and small towns throughout the county. SAMDev, through its provision of specific sites for specific purposes, is the means by which they will be realised.

*

A case close to home – Much Wenlock

In my small town of Much Wenlock the local landowner has offered up farmland along the southern and western boundaries of the town. This has enabled Shropshire Council’s Core Strategy to make an astonishing allocation of up to 500 new houses in the next 13 years – this in a flood-prone, poorly drained town of 2,700 people, where employment opportunities are poor, and the mediaeval road system is not fit for purpose, either for traffic or for parking. In other words, the town is already full, and its ancient centre cannot be changed, short of flattening it.

Shropshire Council’s Core Strategy states that Much Wenlock needs up to 500 new houses in the next 13 years, increasing the town’s footprint by another 50%. The town sits in a bowl with a river running through it. The development in the foreground is one of the newer ones. Its drains were apparently connected to the old town sewer instead of to the separate system for which it had approval. New developments like this have hidden costs for existing communities. This particular problem has not been rectified six years on from the 2007 flood that damaged up to 90 homes.

*

Development = Sustainable Growth?

The ensuing development fest that will be enabled once SAMDev is passed is seen as a means to stimulate growth. The argument seems to be that communities will die if they do not grow in huge tranches. But this is only a point of view, not an absolute truth. There are other models for sustainability, perhaps more meaningful ones. Besides, every community has its particular characteristics that might suggest other narratives; strategies that enable them to grow without necessarily expanding all over the landscape. Of course it is always easier, and presumably cheaper, to build over new ground than it is to reclaim old buildings and clean up brown field sites within existing settlements. Perhaps this is the reason why Councils do not take over unoccupied homes in towns, even though they have the powers to do so?

*

Trading on the past

In places like Much Wenlock house prices are high because, to quote estate agents and developers, “everyone wants to live here”. People want the best of both worlds, a high-spec modern house with multiple en suites, but in close proximity to gentrified antiquity where people live in homes that be cannot double-glazed because of listed building regulations. The new-home dwellers perceive acquired value by association with the past, and are prepared to pay for it. The kind of properties envisaged for the upscaled farmyard site near Oswestry hill fort will doubtless command a premium for similarly nebulous reasons.

Much Wenlock – view towards the town centre, a ‘60s development on the far hillside.

*

In this way, then, developers trade on something that does not belong to them – the historic setting that is cared for and maintained by other people. Buyers buy into the connection, distracted by the ‘look of the thing’. It’s all rather Emperor’s New Clothes-ish. But then if student debt can now be sold on by banks as a commodity, perhaps heritage detraction can also be a tradable commodity. Communities should exact compensation directly from those developers whose poorly designed housing schemes erode the quality of their environment, whether visually or through added strain on existing infrastructure. (In places like Shropshire effective infrastructure provision does not precede any new housing development; nor, if Much Wenlock is anything to go by, does it follow it.) And I’m not talking here about the modest Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) that developers must pay to communities to build the small but useful things like playgrounds and car parks that councils no longer provide. But something far more substantial.

*

How much for this ancient monument?

So what value do we set on a hill fort? Is it worth twenty million pounds say? Fifty? More? Perhaps august academic institutions around the world might invest in shares in our monuments for their scholarly worth, and provide us with the means to buy off developers, or at least keep them at a respectable and respectful distance.

And I am only half-joking here. It would not be so bad if developers in this country built wonderful, good quality eco-houses in versions to suit everyone’s financial capacity, but mostly they don’t. And in the case of Much Wenlock the cost of large new developments around the town has been high – homes flooded from backed up drains and flash-flood run-off.

*

Standing up for heritage

But where does this leave Old Oswestry and all those who are campaigning against developing the nearby farmland?

Since the Guardian article, support has been gathering from across the country and beyond. You can follow the campaign at Old Oswestry Hill Fort on Facebook. But the problem is that there are only so many arguments you can make against unwanted development, and they have to comply with planning law and the Local Authority’s Core Strategy. They include loss of amenity value, visual impact, access, safety and sustainability.

At present, planning laws and high property prices give all the power to developers. If planning authorities cannot base refusal on the strongest case, then developers will opt for a judicial review to get their way. This costs local authorities a lot of money, and so us a lot of money. Developers’ planning consultants write letters to planning officers threatening legal action. You will find such letters in Council files. This is one reason why authorities cave in without a fight.

The heritage consultant’s impact report on the proposed development near Old Oswestry concentrates on view, THE VIEW of the development from the hill fort, and of the development looking towards the hill fort. The impact is considered to be negligible, but this again is a point of view. Housing developments also come with multiple cars, parking issues, garbage storage areas, satellite dishes, and people living their lives as they might expect to do in their own homes. There is also the future to consider. The Trojan Horse concept is a familiar one in development: approval of one development in due course setting a precedent for the next one alongside.

*

So why protect our past?

One would hope that the land around the hill fort would remain as farmland; that the farm could be sold as a farm. Or it might make a good visitor centre for the hill fort, using existing buildings. In reality there is no need to build anything at all in the vicinity of the hill fort. Better that Shropshire Council use its powers to take control of unoccupied dwellings in the town rather than sanction intrusion into the setting of a historic monument of national importance.

After all, why would anyone think that this was a good idea? These ancient places are resorts, and in all kinds of ways. They feed our imaginations and spirits; for children they grow understanding of other times, and other ways of living: all things that in the end make us wiser human beings. And isn’t this the kind of development we really need? People development? And before we carry on building all over the planet, shouldn’t we stop to consider what we already have, and see if some creative re-purposing cannot shape un-used buildings and derelict sites for our future growth requirements? Or is this approach too much to ask of our elected representatives and public servants?

Copyright 2013 Tish Farrell

SIGN HERE: Change.org petition against developing land below the hill fort

*

Find out about protecting your heritage at Civic Voice and Council for Protection of Rural England and join your local CIVIC SOCIETY

*

Related:

Petition to Shropshire Council at Change.org

The Essential Oswestry Visitor Guide

Old Oswestry Hill Fort on Facebook

The Heritage Journal Oswestry Hill Fort Under Attack

The Heritage Journal Old Oswestry Hill Fort: a campaigner asks – “why aren’t EH entirely on the side of the Public?”

The Heritage Journal Old Oswestry Hill Fort Safe?

The Heritage Journal Oswestry Hillfort “top level talks”: will those who care for it stand firm?

The Heritage Journal Oswestry Hill Fort: is it a forgone bad conclusion?