In 1992-1993, during the first years of Zambia’s multi-party democracy, we were posted to Lusaka, Zambia’s capital. Graham was charged with organising the distribution of European Union food aid to drought-stricken Zambians. (Part 1 is HERE, part 2 HERE, part 3 HERE, part 4 HERE and part 5 HERE)

*

*

July 9th 1993

At 19,000 feet we look down on a red-brown world of low escarpments, ridges and valleys. The brown is the tree cover, the scattered miombo and mopane woodland loosing its leaves; the red, the earth exposed between parched grasses. From the cabin window the wilderness looks to run forever. Abstract the gaze and it could be copper sheeting, crumpled, etched and pecked: a visual metaphor for a land long plundered of this valuable mineral.

It is winter in Southern Africa, the dry season. Now and then ribbons of smoke drift up to us. Charcoal burners. The afternoon sun turns remnant streams to silver filaments. And then the plane banks and we’re over Luangwa. Sky blue shot with gold, the main channel looping between wide, pale beaches and exposed sand bars.

It is quite a sight. Even shrunk to its dry season flow, this river impresses. I wonder at the scale of it in rainy season spate. From above you see how it endlessly remakes itself, carving out new ox-bow meanders, stranding the old as stagnant lagoons that later, we learn, are called Dead Luangwa, Luangwa wafa, yet are important wildlife refuges at this time of year.

*

We are on the afternoon flight from Lusaka to Mfuwe – destination Tena Tena Camp, in South Luangwa National Park in Eastern Province. The park lies along the river valley, itself part of the Great Rift system, and covers 9,050 square kilometres. The southern park and its North Luangwa counterpart are renowned for their wealth of wildlife, not least 450 bird species as well the big game.

The camp is run by Robin and Jo Pope, he a Zambian zoologist, and specialist in walking safaris in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe; she a British expatriate and zoology graduate. The full scale walking safaris last a week and more and we can afford only a long weekend, 2 nights at Tena Tena, and one night at Nkwali, the sister camp outside the National Park.

Our plane is a 50-seater. We are welcomed with slices of Madeira cake and shortbread, iced Fanta or Cola. Later, coffee is brought round in a big jug. Somehow it feels more like a train ride than a flight. Touch down, we are told, is in one hour fifteen minutes.

Mfuwe turns out to be a tiny airport, there to serve National Parks’ visitors. Sammy, a young African, Tena Tena’s trainee manager, ushers us, along with a Dutch couple, into the open sided Land Cruiser. Our driver is the camp cook, a South African girl. We’re told it’s an hour’s drive. The Dutch couple are repeat visitors and they are very excited. There is much loud chatter. It’s somehow blurring the landscape.

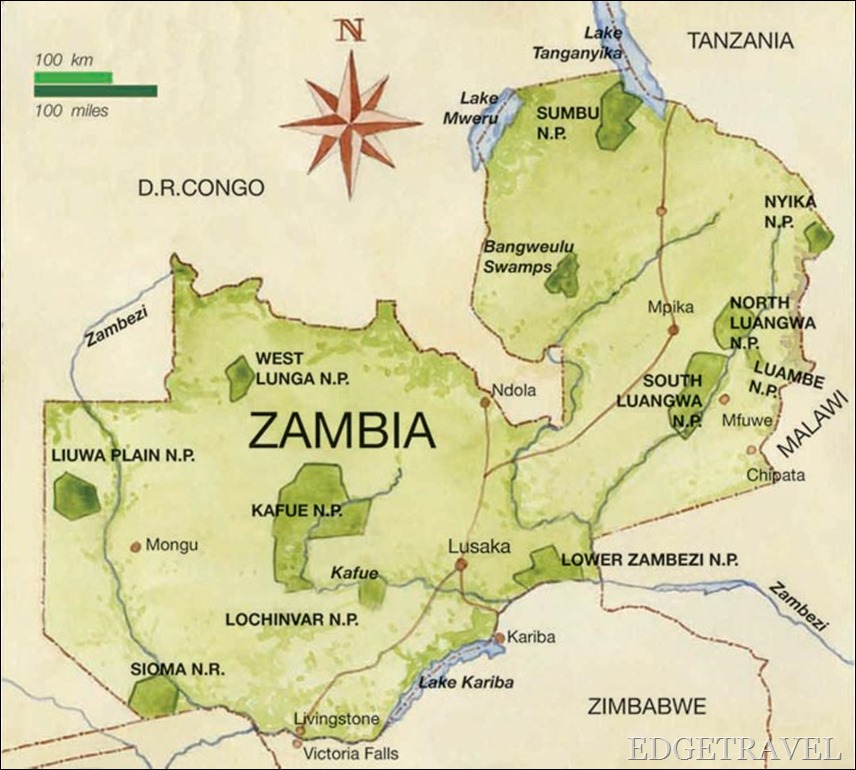

Soon we are leaving the tarmac for dirt roads, passing by homesteads of thatched houses. The roofs, made of thickly laid grass bundles, overhang red and white painted walls and are supported on tree posts. All around are well swept compounds. I also notice the refurbished granaries. After the previous years’ drought, this year’s rains have yielded good maize crops. There will be no further need of Graham’s services when his contract ends in September.

But then comes a dose of reality. As we lurch across a dried up stream, I see a village girl digging into the sandy bed, waiting for a cupful of murky water to well up. A new strand braids-abrades in my consciousness. Why does it take such sights to teach me my good fortune?

I distract myself from inconvenient discomfort with the beauty of the mopane woodland. The trees are graceful and grow widely spaced, as if orchard-planted. The afternoon sun filters through, and I’m oddly reminded of an English beech wood; the suffused russet light on a late October day.

We are in the park now, and park is somehow the right word. There are green swards along the river’s flood plains where puku antelope graze. The disposition of trees in their winter tints suggests an overgrown country estate somewhere in my home county of Shropshire. Except the trees here are winter thorn acacias, lead woods, ebonies, mahoganies, sausage trees and baobabs.

*

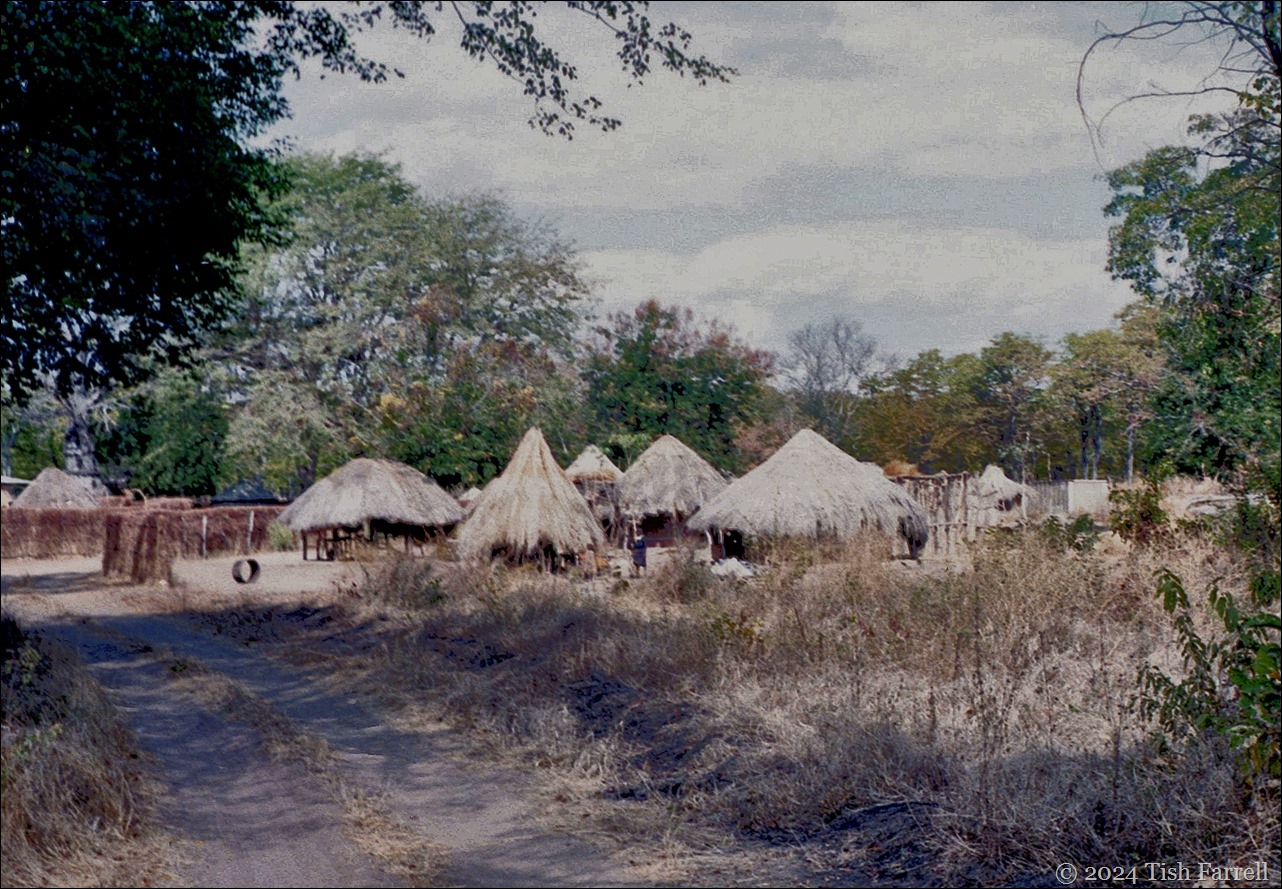

Tena Tena sits on a high bank above the Luangwa, its six thatched roof tents sheltered by trees. The name means temporary home in Nyanja, and we soon learn that, according to park regulations, the camp may only be used in the dry season; no permanent structures allowed. So the whole enterprise (including the tents’ showers and loos) must be packed away before the rains.

The Farrell tent is under a Sausage Tree (Kigelia africana), a stone’s throw from the shelving river bank and within close hearing of much hippo grunting. We’re served tea and cake and told to take a siesta until late afternoon. At sunset we’re back in the truck, and being driven to one of the lagoons, where we stop for sundowner drinks and to watch for any wildlife. Our fellow guests, along with Dutch couple, are Jo Pope’s parents. The foursome are old friends. It feels like a family party, and again there is much noisy chatter. But then the light in lagoons is so breath-taking, it’s hard to be too irritable. Instead, as I watch a flight of Sacred Ibis on a tangerine sky, I long for a camera with rather more range than my little Olympus-trip.

The lagoons, Luangwa wafa or ‘dead’ Luangwa

*

Tena Tena dining room sheltered by a winter thorn

*

When darkness falls we set off across the park. Overhead a million stars. The universe. I find the Southern Cross and, not for the first time that day, wonder if I’m really there, seeing it. The truck is open sided with raised seats. But it’s chilly and dank by the river. I’ve put on all the clothes I have with me but, even with a thoughtfully provided rug, it’s not quite enough. Jo Pope stands beside the driver, wielding the spot light as we rumble into the night. When we brush by clumps of Vick’s bushes, their camphor scent sifts through the night air.

Out on the flood plains, the spotlight picks up hosts of wary eyes – herbivores – puku, impala, a pair of hippos lumbering out for their night-time grazing. We visit a hyena den. A young male cub comes out to look at us. On his second visit he whoops pitifully, a sound that makes the spine quiver.

As we head down riverside tracks, nightjars flutter up from the ground at wheel-height, plumage translucent when caught in the spot light. They look like giant moths. And while we’re focused on smaller things we also look down on elephant shrews going about the nocturnal business of bug hunting.

*

That night in our tent the hippo snorting is ceaseless. I believe I have scarcely slept when hot water is brought to the washstand outside our tent and the 5.30 wake-up drum sounds. Fifteen minutes later there’s a second drum call. The sky is steely grey with the first cracks of dawn. Breakfast is help-yourself tea, toast and cereals from a table by the river. There’s a camp fire to warm us up. As I stare down at the shadowy river, munching toast, I’m suddenly aware of the hippo just below me. It is on the bank, probably too close for comfort, but it’s too soon in the day to believe in such encounters.

By 6.15 we are again in the truck, bouncing on bone-jarring tracks. The light is gauzy so it’s hard to know if I’m truly awake when two hyenas approach through the scrub. They are so gorged on the night’s pickings they can barely move. They slump in the open while we watch.

*

This morning there are many birds to see, pretty Fischer’s lovebirds (bright green with flame coloured heads, yellow bibs), saddle bill storks, eagles, a hammerkop. Then comes a huge herd of buffalo. For a full ten seconds we see it, and then it melts into the bush as if it had never been there. Another mirage then? Later, we have more certain views of warthog, baboon, eland, wildebeest, Burchell’s zebra.

After an 8.30 tea break by a lagoon we head out onto an open plain. It’s an eerie place in the wintery light. A forest of wrecked trees spreads out before us, nothing but burned out trunks, white-grey spikes, strangely luminous. Our guide, Guy, says this landscaping is down to elephants and their driving ambition to have more grassland. They ring-bark the mopane trees which slowly die and then when a bush fire comes through, it finishes them off.

We drive to the salt pan, another strange locale, where salt water gushes forth at near boiling point. As we arrive, a flock of crowned cranes take flight with mournful mu-um cries. We inspect the spring and, it ‘s as we drive away, that we see the lions.

At the salt pans. That’s me in the back of the truck

*

They are lying in heaps under brown bushes, possibly seven in all. Guy says we will take a closer look, but we must keep quiet and stay seated within the profile of the truck. That way the lions will see only the truck, which presents no threat to them.

And so it proves. The lions could not care less. Sleeping time amounts to some twenty hours a day. There are many more hours to get through. We leave them in peace.

*

By now the sun has broken through the cloud, the day growing hot. Lunch is served under a massive baobab, perhaps a thousand years old, Guy says. While we eat coronation chicken and rice, he points out the old wounds on the baobab’s trunk. They were made by elephant poachers hammering in footholds so they could use the tree for a look-out post.

This baobab was once an elephant poacher’s look-out tree

*

That night on the drive we see a great eagle owl, two honey badgers, a genet and six porcupines. The porcupines seem to whiffle along, spines shimmying under the spotlight. Then there’s a moment when I look down from the truck into the dull yellow eyes of a crocodile. It is right alongside. There are two of them, each a metre or so in length, and they are shunting along a shallow channel.

It’s a surreal moment – looking in the eyes of a crocodile. Whatever is being registered there, you surely don’t wish to know. And then in the darkness, we find ourselves snarled up with elephants. They are crossing the track at a point where there are dense bushes either side. But they are moving slowly, since they are also browsing as they go, and there’s no knowing how many there are. But we see their huge shadows, and spot some smaller shadows, and then there’s always that odour. Musky. Earthy. Like nothing else. We quietly reverse and make a wide detour.

*

On Sunday morning we eat breakfast beneath a half moon and the morning star. At 6.30 we set out on a five hour walk. Sean, the South African zoologist is our guide. We also have with us a tracker with the tea things, and White, a national park ranger who carries a rifle. We set off across a dried up lagoon where the previous early evening we had glimpsed two leopard. It is a golden morning as we walk among sausage trees and lead woods whose leaves, we are told, are a cure for asthma. As we go, a grey headed bush shrike calls its mournful one-note call. It is a strange sensation to be walking rather than driving. For one thing, it’s hard to see very far ahead.

The sausage tree is considered sacred by local people

*

Sean is following buffalo spore, this with a view to establishing the exact location of the herd we had glimpsed the previous day. But instead of buffalo we come on a big bull elephant, standing alone in a woodland glade. He is rheumy eyed and elderly. Sean speaks softly and says the elephant is wary: he can make out our shapes but can’t tell what we are. We see his head held high, trying to catch our scent. The trunk lifts and twists, the tip moving like a periscope. We only need worry, Sean adds, if his ears fan out and his trunk swings sideways.

We are all right then. It seems he is not thinking of charging. Then a herd of impala appears behind us and starts barking the alarm. ‘I hope he doesn’t think we’re lion,’ says someone. We retreat quietly.

Now it’s the vegetation that holds our attentions. We walk through tall grass savannah. There are potato bushes, daisies with mauve flowers and salt bushes that we are told are crushed like sugar cane to produce salt. And then, against the distant tree line, we see the huge buffalo herd that had done the vanishing trick yesterday. And at the same moment the nosey impala herd backtracks to have another look at us.

Sean says if they bark again the buffalo may run. We step back among the trees just in time to see eight elephants, including a calf, moving quietly across the grassland, eating as they go. It’s like watching a silent film. We cannot hear them, and so then we are told that elephants effectively walk on tip-toe, the front foot supported by a bed of gristle much like a padded high-heeled shoe. We watch them go.

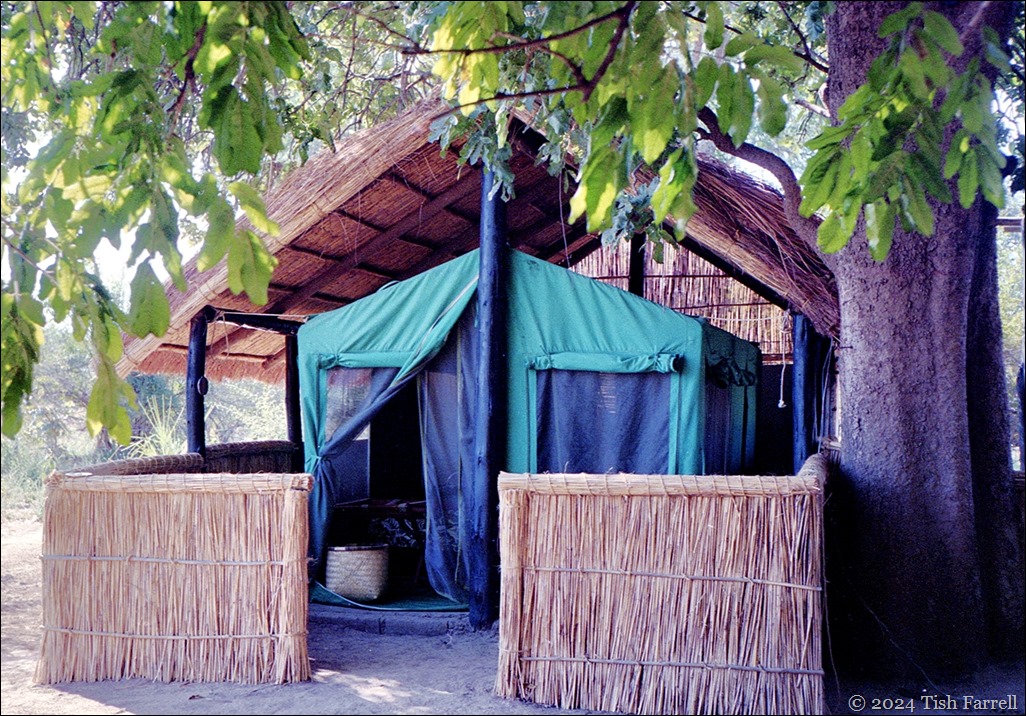

Sean kicks the dust to check the wind. He’s had it mind to show us some lion. Where there are buffalo, he says, lion are not far behind. But with all the detours, he gives it up and says we’ll have a tea break at a fisherman’s camp outside the park.

The camp is on the bank of a dried up lagoon. The fishermen who spent the night here are long gone, but their fire smoulders on, and one of our party tries out the bamboo sleeping mat. There’s a hippo skull for a neck support. There are also bamboo sheds with racks for drying the fish. Sean says some of the lagoons still hold bream, which are caught using dug out canoes and conical bamboo fish traps. In passing, he says it can be dangerous work; a few days earlier a fisherman was killed by a hippo.

We could take this last remark as a warning. Except we don’t.

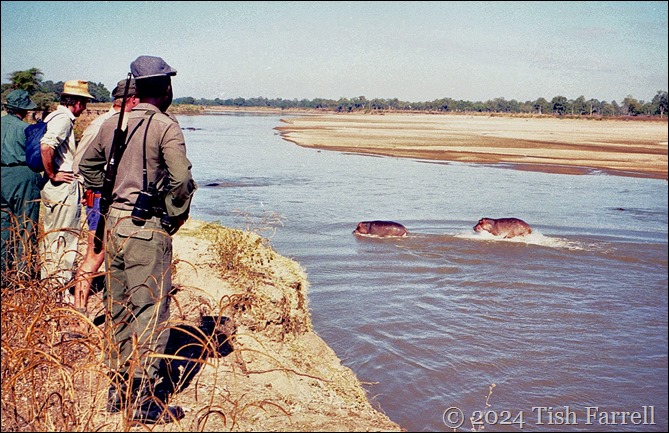

By the time we leave the camp and head back to main river, the sun is hot. From some distance away we spot a bull hippo trying to return to the water. He’s left it late after a night out grazing, and has come back to the river where the bank is high and steep. Being out in the sun risks serious burning and he is growing increasingly distressed with every failed attempt to descend.

We think ourselves well out of range as we watch his antics. Sean says he is probably a young bull expelled from his group, unable to win a herd of cows for himself. Someone laughs at another botched descent. And he hears. And then he turns.

The bull hippo that charges us is on the bank under the small tree

*

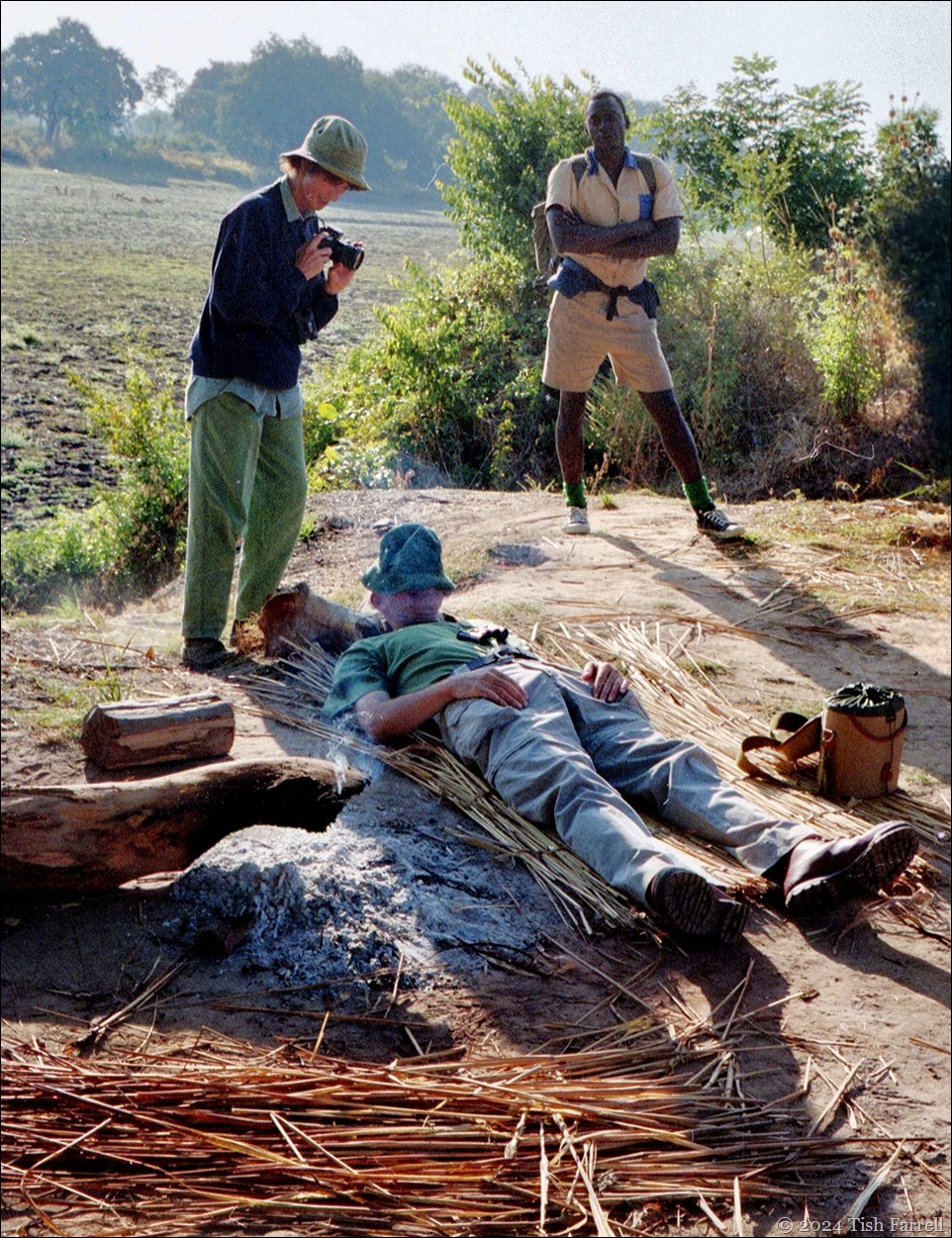

Sean and White react at once. They move forward clapping their hands, but when the hippo keeps coming, White ushers us back towards the fisherman’s camp, telling us to take refuge behind a beached dug-out. Meanwhile Sean is still clapping. White joins him, rifle at the ready.

White guides us to a suitable refuge, then returns to the river to deal with the charging hippo

*

It is a nerve-wracking few minutes. But then after the initial rush, the hippo runs out of steam and veers off into the bush. We regroup and Sean says White was indeed prepared to shoot the hippo if he had not backed down. It’s a disturbing thought – that our safari-goer carelessness might have warranted the bull’s despatch.

But then we see the problem is not resolved. We are near the camp, yet now there is an angry hippo somewhere in the scrub between us and it. We have to do a massive detour. It’s approaching midday by now, and I’m starting to know how the hippo felt in his overheated state. I’m hungry too, and only briefly diverted by the sight of fish eagles and African skimmers. And besides, too, I have already seen enough of hippos for one day.

*

On Sunday afternoon we transfer to Nkwali. It’s outside the national park near Kopani, a good hour’s drive and we’re lucky to have Robin Pope as our personal chauffeur-guide. He tells us so much, but by now it’s becoming hard to process. Later, though, I find the things I learn that afternoon inform a short story, Mantrap, published first in the US children’s magazine, Cricket, in 2003, and then in later teen quick-read chapter versions for Evans and Ransom Publishers.

*

That night, in our new temporary home by the Luangwa, it is not hippos that keep us awake…

To be continued.

copyright 2024 Tish Farrell

#SevenForSeptember

Thanks Tish!

Magic stories…

Is that you, David????

Certainly is, Tish!

Brilliant. Been thinking of you, while I’ve been writing these pieces. Hope all is well up in Derbyshire. Txx

It’s actually the Yorkshire Dales!

Still keeping on keeping on, not getting any younger unfortunately!

xx

Now I am confused. I thought I was talking to someone from Lusaka days.

Sorry Tish, never been to Lusaka, lots of other places though!

So you posted a comment as David Walker?

Er, yes so I did!

That’s my Sunday name!

I have a number of email accounts, some personal others business, that’s the name that goes with the ArielVH one, somehow WordPress seems to have mixed them up!

xx!

PS loved your comment about the elephant vandals!

Like the notion of a Sunday name.

well.

with all the Disney hype it’s best to remember these are “wild” animals to be respected in their own territory.

Yes, Beverly.

I recognise most of the places you’ve photographed, Tish. It takes me back… Lovely memories

Was thinking of you and how much of this territory you had probably covered. And yes, happy times, Ian.

How lucky we were

Yes, we were.

love these stories – keep ’em coming, please.

So pleased you’re liking them.

honoured your incredible and beautifully written stories are part of squares, but also somewhat terrified by the hippo encounter!

Yes hippos are forces to be reckoned with. They seem to have short fuses!

Waiting for the next installment!

A wonderful and no doubt life-changing experience.

Yes, life changing. Even in the virtual revisiting 🙂

Such a rich and exciting experience! The whole thing must have felt somewhat surreal, as if you were dreaming, or in a movie.

Alison

Yes, so much was surreal. I think it had much to do with the Luangwa landscape giving the impression of being in Europe. The unruly wooded, overgrown garden look in some places and the orchard-planted look in others. i.e. Seemingly quite low-key and almost familiar. And then you spot an elephant or hippo.

What an immersive post: the scenes you describe beautifully painted, and sometimes raaising my anxiety levels too!

Many thanks, loyal reader 🙂

😊

I don’t read many blog posts while travelling but I’m sp glad I made time for this one. Your text is so vividly written, I really felt I was there with you on those safari drives amd on that walk. The latter took me back to our time in Botswana when we encountered a bull elephant on a similar walk, but nothing so scary as your charging hippo!

Thanks so much for taking the time both to read and comment on my post, Sarah. Happy travels.

What a great experience Tish. Thanks for taking us there, it’s amazing. Now I can’t wait to find out what’s keeping you awake!

Happy to oblige with that info, Anne. I’ve already posted the next instalment 🙂