Yesterday we woke to the first hard frost of the year. When I looked out of the bathroom window to the top of the town, there was a cascade of white cottage roofs instead of the usual grey slate. And all glistening too…

Because best of all, there was also sun. SUN by god – and the weather people’s promise it would stay all day. What a gift. After weeks of rain between gloom and deluge, plus a stint of accompanying coughs and sneezes, I knew we should go out and make the most of it in one of Shropshire’s most majestic spots.

To Bury Ditches, says I. We can take a packed lunch. And so we did.

It’s only a five minute drive from our house, but up a very steep hill. For us unseasoned walkers, it’s too far to go on foot. The hillfort lies in Forestry Commission land, which means there is a car park, but the path to it rises further still above ‘monolithic’ stands of conifer, lit up here and there by the odd bright oak, or the orange haze of wintering larch.

*

The morning sun had melted much of the frost, though it lingered in the verge shadows and in the valley bottoms. The air was absolutely still. So still, and so utterly silent, it seemed the world had stopped. It was a fine moment to come upon an ancestor, albeit one, turned to wood. What kind of magic was this?

*

When we reached the hillfort, I tried to capture some idea of how it looks on the landscape, the scale of the ramparts – huge but nonetheless much diminished after 2,000 years of weathering. But it’s always impossible – the light not right, the site too overgrown, the earthworks ill-defined. And then there is the problem of the enclosed ground: all quite featureless; a great expanse of rough pasture, with nothing to fix on, or frame.

Here’s an artist’s reconstruction of the site, then a couple of my rampart shots.

*

For some better hillfort views than I could manage, please have a look at Virtual Shropshire’s page on Bury Ditches.

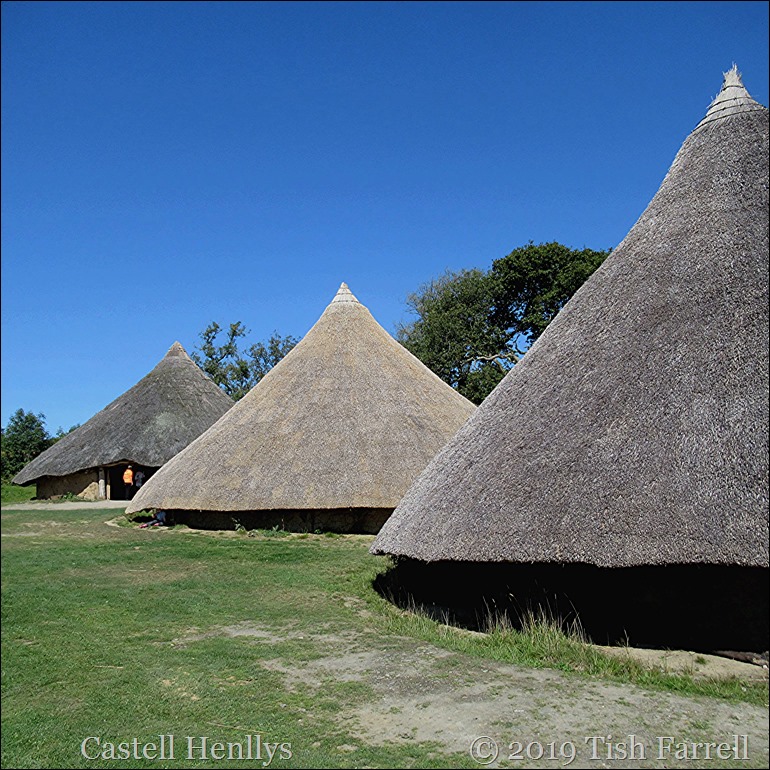

And so what are we left with? A sense of place, of space, the commanding views, the resonating mystery of who exactly built these monumental structures over 2 millennia ago. They are found across the uplands of Great Britain and yet we know so little about them. Some of course have been excavated and yield signs of village settlement inside (Castell Henllys). Some also revealed evidence of siege (e.g. Maiden Castle). Others seemed to have been simply places of refuge in times of war. Or perhaps also gathering places for festivals and markets. But the big disadvantage of hilltop refuges is they usually lack easy access to fresh water.

One thing we can say: these places were hugely important to the ruling hierarchies of the Iron Age people who built them. Imagine the man and woman hours involved, digging into bedrock with bone and antler picks and mattocks (for at this time iron, a scarce and valuable commodity, was reserved for the making of prestige weaponry not tools), heaving loads of earth in precipitous locations where horses and carts could scarcely serve the purpose. Yet…And yet…when freshly excavated in limestone country, or better still on chalk, the ramparts of these forts would have looked marvellous, glistening white on the skyline; visible for miles.

So if I couldn’t quite bring you a hillfort, here are the vistas we enjoyed, looking out, this after perching in a heather clump to eat our packed lunch. Herewith Shropshire and the Welsh borderland:

*

By 2 o’clock the sun’s warmth was gone, the remnant frost creeping back, fingering parts not properly wrapped up. We were glad to stride back to the car. A five minute drive home and we were by the log fire with a cup of tea. Such a little journey and yet we had been transported to another world and time. Passports not needed. Only willing hearts and minds and a small car.