This is an edited re-run of an old post – and a much longer read than usual…

*

October 1992 and I’m expecting to start a new life in Medway, Kent, but instead I find we are off to Lusaka. It is hard to take in. I am barely back in England after nine months in Kenya where we lived out of a Land Rover, plying the Mombasa Highway. My heart is still in the Ngong Hills, the knuckle-shaped peaks that were my last view of East Africa before the plane rose through the clouds and headed for London via Bahrain. In that moment I find myself weeping for the loss of the Ngongs, recognising, with a twinge of shame, I would never weep like this for my homeland.

Due to ticket problems I have to travel back to the UK alone. G will follow the day after. When we say goodbye at Nairobi airport there is no inkling of another overseas contract. Yet two days later when we meet up in England, the first thing G says is: how would you like to go to Zambia?

Zambia, I echo blankly. How would I know if I want to go there? But with barely a pause, I say yes; I’m up for it. I’ll find out later if I’m going to like the place. Besides, whatever happens, it’s bound to be interesting.

When we tell friends and family where we are going, they also look blank. Zambia, they say. What did it used to be? It is only months afterwards that I see how loaded is this seemingly simple question, how unfathomable the answer. What indeed did Zambia used to be – before it was Northern Rhodesia – before David Livingstone passed through it in search of lost souls and the Nile’s source, and claimed the falls known as Mosi oa Tunya (The Smoke that Thunders) for Queen Victoria; before the south’s Zulu Wars that pushed many displaced communities across the Zambezi?

We’re expected to leave within the month, but due to various administrative foul-ups, this stretches to two. It gives us time to unpack our Kenya life, catch up on dental work, have the jabs we have not already had, say hello and goodbye to relatives, and to get married. This last event takes place briefly before a handful of guests in a Bridgnorth building society office where the registrar has occasional premises. Our little marriage party finds itself queuing for attention alongside Friday morning withdrawers and depositors. It all seems fittingly bizarre for a life that no longer fits the norm.

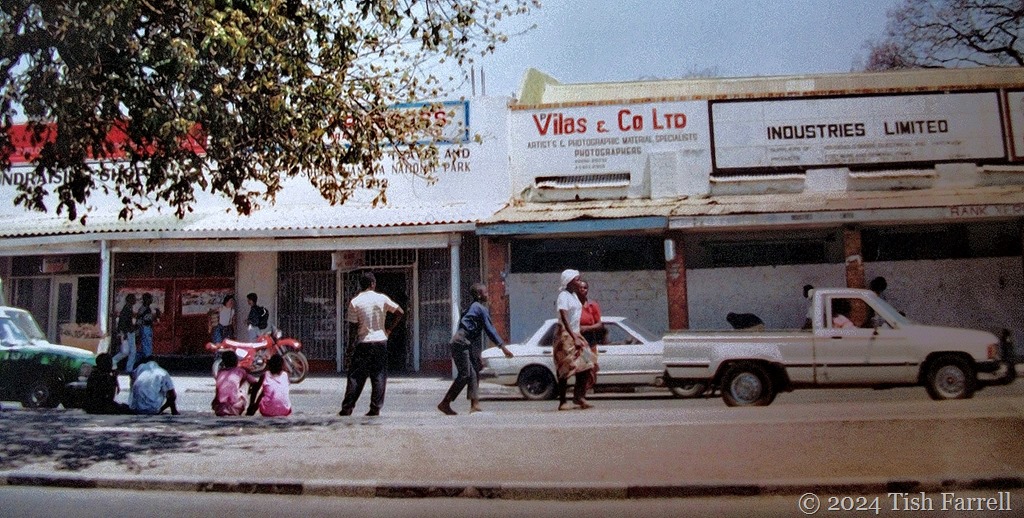

Lusaka’s main street, Cairo Road, looking south

*

At this point I am still no wiser about our destination. In these pre-Google days there is little time for research. To my annoyance, too, I find there are no handy books on Zambia, not in the public library, nor in the bookshops. By the time we come to leave, we have only the sparse Foreign Office briefing notes to go on. They speak of the climate and the kind of clothing we will need, and of the possibility of having to take a driving test if we want to drive in Zambia.

No clear picture of the country emerges. I am becoming increasingly irritated at the lack of information, as well as at my own ignorance. How can I, an English woman, not know a thing about a land that Britain ruled and exploited for over sixty years, a land we only quitted in 1964 while I was in still at school? Why wasn’t it on the curriculum along with Cicero and Chekhov? How can the existence of a former protectorate pass so swiftly from the protecting nation’s consciousness? How can it become so very unimportant?

Then suddenly it’s too late for righteous indignation; it’s all down to family farewells, and wondering if the right things have been packed, when there is no way of knowing what the right things should be. Of necessity, it becomes a matter of travelling hopefully and telling ourselves that the contract is for ten months only. And ten months isn’t long, is it?

*

So, November 1992 and we fly into Lusaka with the rains. It seems like a good omen – to arrive with rain. There has been severe drought over southern Africa for at least a year. Crops have blown to dust, rivers run to sand, and the granaries lie empty. In remote districts, we later learn, villagers have been surviving on a diet of wild mangoes. To add to their misery, the wildlife is hungry too. In one district villagers have been barricading themselves into their homes. The local lions have developed a taste for canine flesh and are breaking down house doors at night in order to snatch the dogs from the midst of their terrified human families.

And of course, this is why we are going to Zambia; famine is taking us there. G has been seconded from the Natural Resources Institute in Kent to the E. U. Delegation in Lusaka to supervise the distribution of European Union food aid to starving Zambians. The country’s then new President, Frederick Chiluba, tells the Head of Delegation that he does not trust his ministers to do the job. The consignments of maize meal and cooking oil must therefore be distributed through church missions and the Red Cross. Zambia is a big country, the size of France and the Low Countries combined. G will be in charge of logistics: checking the contents of grain stores, getting trucks on the road and ensuring that loads reach their intended destination. His boss at NRI is sure he is fitted for the task, although he has never done anything like it before.

Food aid awaiting distribution in a Zambian warehouse.

*

In Kenya, as a crop storage specialist, he had been dealing with another kind of food crisis – the spread of a voracious pest that gobbles up maize – the Larger Grain Borer. This beetle is a native of South and Central America, and (ironically) came to Africa in the 1980s in a food aid consignment from the United States. It has no natural predators in its new homeland and, across a continent where maize is many peoples’ staple crop, it also has all the food it can eat. If a grain store is infested you can hear the jaws of these tiny creatures gnawing the cobs to dust.

In Zambia we find the beetles are already there too, spreading out into villages along the line of the Tazara Railway that links land-locked Zambia to the port of Dar es Salaam. The Chinese built the line in the 1970s to provide Zambia with an external trade route through Tanzania after Ian Smith’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence in Southern Rhodesia cut the country off from all points south. Now the Tanzam is a handy vector for crop pests and thus, through such unintended consequences, is the frequent folly of donor good intention compounded. It is the sort of thing that happens in African countries all the time. It makes us question then (as we will do many times over the next few years) the ethics of our presence on the continent.

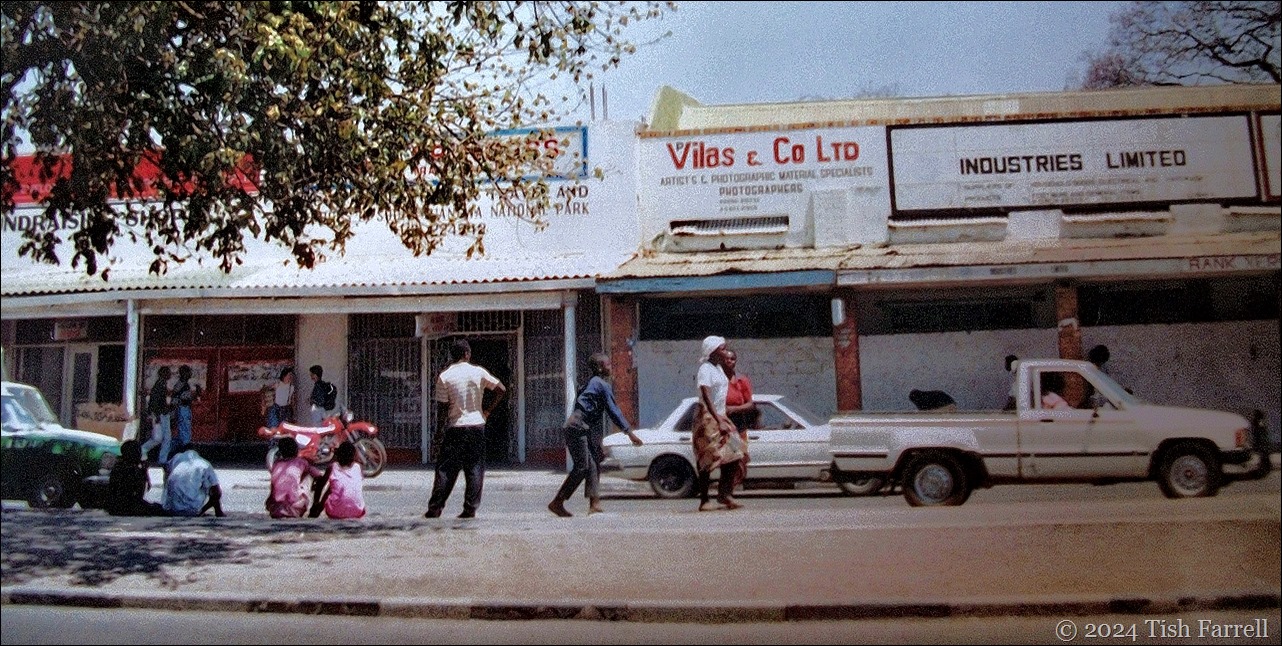

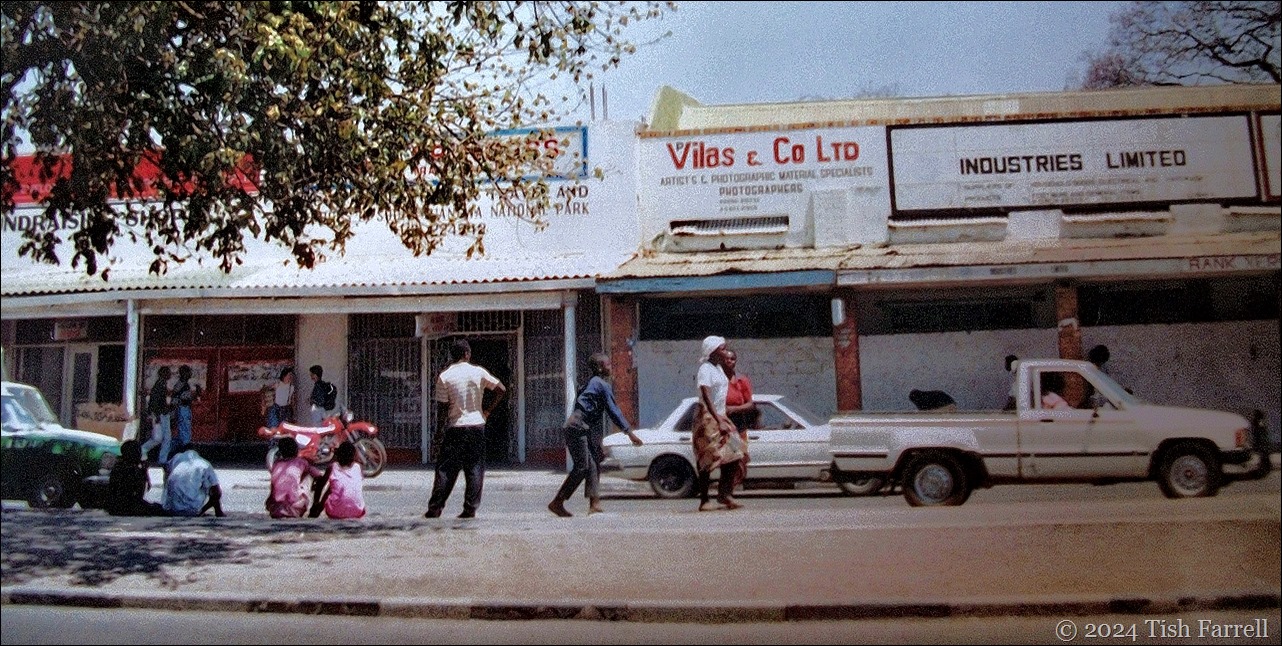

Cairo Road looking north

*

That November morning, then, as we make our descent through grey skies into Lusaka International Airport, I note only how flat and tamed the landscape looks: large square fields of European-owned ranches (Lonrho, for one, is a big player here); service roads and farm buildings laid out in orderly grid patterns. It is also very green and looks more like France than the Africa I have come to know. I suppose I feel a little disappointed. It is bush country that I have fallen in love with, the smell of it triggering some ancient genetic memory that tells me that such landscapes mean home.

Once down on the tarmac, and as a matter of courtesy so we will not get wet in this welcome downpour, a bus arrives to ferry us the short distance to the low white terminal building. Our fellow travellers are European businessmen, each shouldering his laptop bag. By contrast, a tall African in a well-cut suit emerges from the First Class cabin wielding only a shiny new golf club. It seems utterly incongruous, as if he has just stepped out of a London taxi after visiting a golfing shop rather than flying half way across the world. It crosses my mind that I like his style.

By now I am both jet-lagged and deeply anxious about the forthcoming immigration process. Still fresh in my mind is the stony-faced inscrutability of Kenyan officialdom when I twice visited the notorious Nyayo House immigration department to extend my three-month travel visa; I recall the hours left in limbo, sitting amongst distressed Somalis and Ethiopians, all trying to secure sanctuary away from troubled homelands. But suddenly I see it’s not going to be like this. The officers, as they take their seats at the immigration desks are all smart young women. They are laughing and chatting and, when we hand them our passports and paperwork, they are still smiling, and at us.

Next we have our first, but fleeting taste of the diplomatic life, as G’s new boss steps up and introduces himself. His name is Bernard. He is French, frenetic and instantly engaging. He whisks away our paperwork and deals with it in minutes. There is then a worrying delay before we can claim our bags. Bernard tells us that British Airways on this route are well known for leaving cases behind in London. Finally, though, we have our luggage and are propelled into Bernard’s Peugeot, Bernard talking non-stop. He apologises for his poor English, saying that this is his first posting to an English-speaking country. Mauretania and Madagascar were his previous postings. Worryingly, he adds that he hopes we will speak some French. Beside me, looking wan, G winces; he does not fly well. He can barely speak. When he does, it is to utter a customary response in KiSwahili. I’m beginning to feel hysterical.

Soon, though, all smooths out as we cruise along the Great East Road into Lusaka. There is little traffic (not like Nairobi), and the place has a small-town provincial air – wide streets lined with jacarandas shedding mauve petals and acacias with russet coloured flowers, red-roofed villas. We pass the turn to the University of Zambia, the entrance to Lusaka’s agricultural show ground. The side walks are filled with people walking – young men in loose shirts and smart front-pleated pants striding out, country women in ankle-length chitenge wraps, city girls in high heels and sleekly cut frocks, and who seem to flow along the street. There are roadside stalls selling garden surplus – mangoes, tomatoes, okra, spinach.

EU Delegation, Lusaka

*

And I am just thinking that I can cope with this when we swing into the grounds of the five-star Pomodzi Hotel, and Bernard’s car is instantly lassoed in chains whose ends the hotel porter quickly padlocks to an adjacent post. I have never seen nor imagined anything like this. Bernard explains that this is a necessary procedure even though it will only take a few minutes to escort us to reception. I see that other guests’ cars are similarly chained. It is then that my one sure piece of Zambia information surfaces.

*

All along we have been ignoring it, that in that year of 1992 the country has a big security problem. Some months later the reasons for this become clear, but for now I am struggling to absorb this apparent evidence of an expected car-jacking – in broad daylight, and in such orderly and upmarket surroundings. I gaze, bemused, at the tail-coated porter who is now ushering us into the hotel foyer. After the humid warmth of outside, the hotel is frigid with air conditioning. The reception area is cavernous, all grey-white marble. A trolley appears and our cases are stacked upon it. They look shamefully shabby in these austerely smart surroundings. The porter politely motions me towards a comfortable armchair while G registers. This always takes ages, and by now it is lunchtime and I am hungry and yet too tired to want to eat. Then suddenly there are Englishmen everywhere. They seem to issue as one from the lift.

“Hello. I’m David…Peter…Tim…Paul…Alan. We’ve not been introduced but…”

As welcoming committees go, it is well meant but too much, and I wonder if I’m responding sensibly. They turn out to be G’s fellow consultants from the Natural Resources Institute in Chatham, Kent, out on short-term missions relating to crop storage and food security. They include G’s head of section, the man who seconded him to the E.U. Delegation. He’s just off to Zimbabwe, and hardly have we reached our room than the phone rings, and G is summoned to an impromptu meeting and a trip round a Lusaka grain store that has flooded, none of which has anything to do with his present posting. He goes off looking terrible while I collapse on the bed, trying to come to terms with my new surroundings.

Here we are back in Africa, back in the so-called developing world, here to help deal with a food crisis. Yet now I find myself in a room that has more of comfort and opulence than I’m used to in England. There is a huge colour television that shows American and British world service programmes. There is a telephone by the bed and another beside the lavatory. The ivory tiled bathroom has abundant hot, clean water and piles of soft white towels. The flask of drinking water is chilled. We have our own veranda. The room service menu offers club sandwiches, burgers and steaks. A polite notice on the writing desk requests guests not to tempt the staff by leaving their valuables unattended.

This is a hotel designed not so much for travellers and tourists, but to cater for the expectations of international entrepreneurs. Its luxury is hard to reconcile with the hardship that G has been brought here to relieve. This is only the first of the multiple contradictions that we will encounter over the next ten months. We learn not to dwell on them, and so become part of the contradictions.

*

Now in Lusaka, we find ourselves dropped into a diplomatic no-man’s-land. Although G works for a British government institution and has been deployed by them on official business, neither the EU nor the British High Commission want to altogether acknowledge our presence in the country. We gather that the BHC has some bee in its bonnet about the cost of air-lifting us back to the UK in the event of some great ill befalling us. This is a puzzling response when all G asks for is some anti-malarial pills. They are not keen to give us any, since this establishes responsibility.

There is also a problem about finding us somewhere to live, this despite the fact that both missions have their own staff accommodation. We have been sent out with a stash of travellers’ cheques to pay for ten months’ rent and to buy a car, but house rents in Lusaka are twice the allowance we have been given. A Delegation secretary, a white Zambian, takes pity on us and directs us to a small company compound of eight houses where local Zambian Europeans and Asians live.

There is one house vacant, and we can just about afford it. The accommodation is very lowly by diplomatic standards, and full of dog-haired furniture, but we still manage to upset BHC consular etiquette because the compound has a swimming pool. Only officials of the higher orders may be allocated houses with pools. BHC staff kindly let us know of our gaff at social functions, although we wonder what it has to do with them since they were so unwilling to acknowledge our existence. Clearly the swimming pool has got under somebody’s skin.

Our house on the Sable Road compound and a glimpse of the undiplomatic pool

*

Home for ten months.

*

Then, when we are among EU Delegation officials and their white Zambian staff, we are constantly regaled with tales of car-jackings, house break-ins, muggings and murder. At his house, Bernard has been newly issued with a gun and a short-wave radio to summon security in case of attacks by the locals. We presume that we are not important enough to warrant this scale of protection. When, after some weeks, I return to Zambian Immigration to renew my passport, and once more am treated with only good hearted African courtesy, I consider switching my nationality to Zambian.

To be continued…

Copyright 2024 Tish Farrell

![Kamwala-roadside-furniture-market-ed[1] Kamwala-roadside-furniture-market-ed[1]](https://tishfarrell.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/kamwala-roadside-furniture-market-ed1_thumb.jpg?w=932&h=1293)